In a recent TechCrunch post, Russell Brandom proposed a "5-Level Commercial Ambition Scale" for foundation model companies—ranging from Level 1 ("True wealth is when you love yourself") to Level 5 ("We are already making millions of dollars every day"). The scale is clever, and it correctly identifies that ambition, not current revenue, is the relevant variable for evaluating early-stage AI labs.

But ambition is the wrong lens entirely.

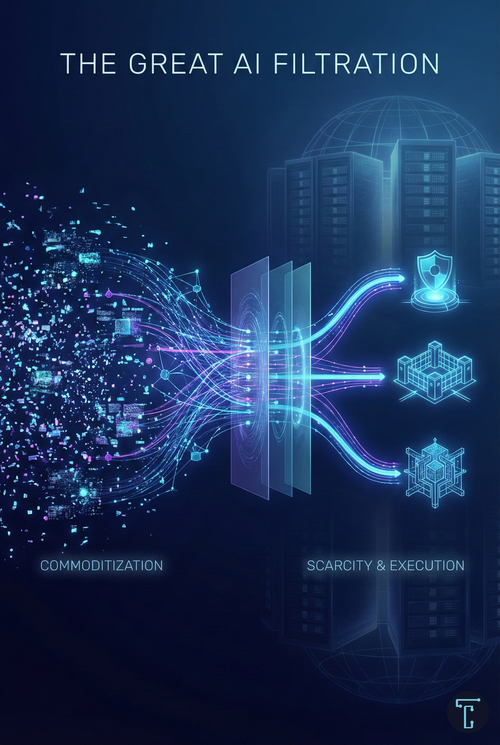

The question facing the new generation of AI labs—Safe Superintelligence, Thinking Machines Lab, Humans&, World Labs, and their peers—is not whether they want to make money. It is whether they can. More precisely, it is whether they control something scarce enough to command durable economic rents in a market where the most powerful companies in history are spending $600 billion annually to commoditize the very capabilities these labs are trying to build.

The answer, for most of them, is no. Not yet. And for some, not ever—unless they fundamentally reconceive their strategic position.

The Commoditization Clock

To understand why, we must first understand what has changed since 2023.

In the early days of the current AI wave, capability was scarce. GPT-4 could do things no other system could do. Access to that capability—whether through API or partnership—was valuable simply because it was rare. This created the conditions for the "Fund Cushion" phenomenon: venture capitalists poured billions into any team that seemed capable of producing frontier models, on the theory that capability itself would eventually translate into capture.

That theory is now being stress-tested.

The capability frontier has not stopped advancing, but it has become crowded. OpenAI, Anthropic, and Google are all operating at roughly comparable levels of reasoning performance. More importantly, they are engaged in aggressive price competition. Inference costs have fallen 280-fold for GPT-3.5-class models over the past 18 months. Hyperscalers are subsidizing this decline because they play a different game: they sell compute, cloud services, and enterprise relationships. The model itself is becoming a loss leader.

This creates a brutal dynamic for independent labs. Every month, the baseline capability that was once their moat becomes table stakes. A lab that raised $2 billion in 2025 to build "the next frontier model" may find by 2027 that its frontier has become everyone's floor.

The strategic question, then, is not about ambition but about scarcity. What scarce resource does each lab uniquely control, and how durable is that scarcity?

The Three Archetypes

Examining the current landscape, we can identify three distinct strategic archetypes that labs have adopted—consciously or not—in response to this challenge.

The Sanctuary

The first archetype is the research sanctuary: an organization that explicitly rejects commercial pressure in favor of pure scientific inquiry. Safe Superintelligence Inc. is the canonical example. Founded by Ilya Sutskever after his departure from OpenAI, SSI raised over $3 billion at a $32 billion valuation with no product, no revenue, and no intention of having either in the near term. The pitch is a "straight shot" to superintelligence, unencumbered by the distractions of product cycles.

The sanctuary model has historical precedent. Bell Labs operated this way for decades, producing Nobel Prize-winning research on the back of AT&T's monopoly profits. Xerox PARC invented the graphical user interface, Ethernet, and object-oriented programming. The problem is that neither Bell Labs nor PARC captured the commercial value of their inventions. AT&T did not become the dominant computing company; Apple and Microsoft did. Xerox did not build the networked world; Cisco did.

SSI faces an even more acute version of this problem. Its research is funded not by monopoly profits but by venture capital with a 7-10 year liquidity clock. Sutskever himself has acknowledged the constraint: if timelines stretch to "70 or 100 years," the straight-shot approach becomes untenable. More tellingly, he has said SSI's models will "learn from deployment"—a concession that pure research, at some point, must touch commercial reality.

The sanctuary strategy works only under two conditions: either you achieve your breakthrough before the capital runs out, or you find a patron (a government, a hyperscaler) willing to subsidize indefinitely. The recent departure of co-founder Daniel Gross to Meta's superintelligence team suggests that at least some insiders believe SSI may need to make a choice before the runway ends.

The Infrastructure Provider

The second archetype attempts to avoid the commoditization of models by positioning as infrastructure—the "picks and shovels" strategy. Thinking Machines Lab, founded by former OpenAI CTO Mira Murati, exemplifies this approach. Their first product, Tinker, is an API for fine-tuning language models that abstracts away the complexity of distributed training.

The infrastructure strategy appears sound in theory. If models are commoditizing, own the layer beneath them. Help enterprises customize foundation models to their specific needs, and capture value through that customization.

The problem is that this strategy runs headlong into the hyperscalers. AWS Bedrock, Google Vertex AI, and Azure AI already offer fine-tuning services. They have enterprise relationships, compliance certifications, and the ability to bundle AI services with storage, compute, and networking at margins a startup cannot match. Tinker may be technically superior, but "better" is rarely enough when the incumbent can offer "good enough plus everything else you already buy from us."

The recent turmoil at Thinking Machines Lab—the firing of CTO Barret Zoph, the departure of multiple co-founders back to OpenAI, and reports of unclear product direction—suggests that even world-class research talent cannot cover fundamental strategic ambiguity. When your core team defects to the very company you left, it signals that the differentiation thesis may no longer hold.

The Vertical Specialist

The third archetype sidesteps generalist competition entirely by focusing on a specific domain where unique data, physics, or workflows create durable barriers to entry. World Labs, founded by Fei-Fei Li, exemplifies this approach.

World Labs does not compete to build the best chatbot. It builds "spatial intelligence"—models that understand 3D space, physics, and geometry. Their product, Marble, generates persistent, interactive 3D environments from text, image, or video inputs. The immediate applications are in gaming, VFX, and architectural visualization, but the strategic vision extends to robotics training, industrial simulation, and digital twins.

This is a fundamentally different strategic posture. Instead of racing OpenAI and Anthropic to the next frontier of language understanding—a race that requires billions in compute and where victory is temporary—World Labs is building capability in a domain where incumbents lack the data or specialized research focus to compete effectively.

The evidence supports the strategy. World Labs launched Marble in November 2025 with clear pricing tiers ($20-$95/month), documented use cases, and enterprise pilots. They are now reportedly raising at a $5 billion valuation. Unlike SSI or Thinking Machines Lab, they have a product generating revenue in a category they defined.

The Strategic Imperative: Specificity Over Scale

The lesson from these three archetypes is not that one is right and the others are wrong. It is that the path from "research lab" to "sustainable business" depends entirely on identifying and controlling a source of scarcity.

For SSI, the scarcity thesis is breakthrough research—the belief that their team can solve problems no one else can solve, and that solving those problems will be so valuable that commercialization will follow naturally. This is a high-variance bet. If they achieve a genuine breakthrough in alignment or reasoning, the valuation will look cheap. If they don't, they become an expensive research project that eventually gets absorbed by a hyperscaler.

For Thinking Machines Lab, the scarcity thesis is operational expertise—the belief that their experience building ChatGPT gives them unique insight into how to make AI systems reliable at scale. The problem is that this expertise is embodied in people, and people can leave. The January 2026 exodus proved that when multiple co-founders departed within months of the company's founding. Human capital is a fragile moat.

For World Labs, the scarcity thesis is domain specificity—the belief that spatial intelligence is a fundamentally different problem that requires different data, architectures, and commercial relationships. This thesis is more defensible because it is more bounded. World Labs does not need to outrun OpenAI; they need to outrun other spatial intelligence companies, of which there are far fewer.

What Humans& Gets Right (and Risks Getting Wrong)

The newest entrant, Humans&, offers an interesting test case. Founded by alumni of Anthropic, xAI, and Google, they raised $480 million at a $4.48 billion valuation in January 2026 with a thesis around "human-centric" AI—tools that enhance collaboration rather than replace workers.

The philosophical differentiation is clever. Where OpenAI and Anthropic optimize for autonomous agents that work independently for hours, Humans& proposes to optimize for models that "coordinate with people, and other AIs where appropriate, to allow people to do more and to bring them together." The technical emphasis on long-horizon memory, multi-agent reinforcement learning, and user understanding points to a genuinely different product category.

But the strategic challenge is severe. "Collaboration software" means competing with Microsoft (Copilot), Salesforce (Agentforce), and Google (Gemini for Workspace). These are not just well-funded competitors; they own the surface area of productivity where collaboration happens. Building a better AI for Slack is pointless if you don't own Slack. Building a better AI for Google Docs is futile if Google can ship a good enough version to every user for free.

For Humans& to succeed, they need to find a vertical or workflow where incumbent collaboration tools fail, where human-AI coordination creates measurable value, and where they can capture that value before the giants copy them. CEO Eric Zelikman's comment that "the model will coordinate with people, and other AIs where appropriate" suggests they understand this, but the path from philosophy to product remains unclear.

The Enterprise Paradox

The backdrop for all of these labs is an enterprise market that desperately wants AI to work but cannot figure out how to deploy it. According to recent surveys, over 80% of companies use AI in some capacity, but only about 4% have achieved a mature, enterprise-wide deployment. The vast majority are stuck in "pilot purgatory"—experiments that demonstrate value but never scale.

This creates a paradox. The market for enterprise AI is theoretically enormous—McKinsey estimates trillions in potential value creation. But the realized market is much smaller because enterprises cannot operationalize AI at scale. They struggle with data quality, integration complexity, governance requirements, and the fundamental difficulty of teaching AI systems business logic.

The labs that will win the next decade are not necessarily the ones with the best models. They are the ones that solve the deployment problem—making AI not just capable but reliable, not just smart but trustworthy, not just powerful but governable.

This is why Anthropic has gained so much enterprise share (now estimated at 40%, up from 12% in 2023). It is not because Claude is dramatically more capable than GPT-4; it is because Anthropic has invested in the boring stuff—zero data retention policies, copyright indemnity, constitutional AI, and enterprise security certifications. They bet that trust matters more than benchmarks, and the enterprise market has validated that bet.

The Path Forward

For the new generation of labs, the strategic path forward requires answering three questions:

First, what is your source of scarcity? If the answer is "we have great researchers," you are building on sand. Researchers can leave. If the answer is "we will build the best general model," you are in a race you cannot win against opponents with orders of magnitude more capital. The durable sources of scarcity are proprietary data, domain-specific expertise, and trust relationships that take years to build.

Second, what is your theory of deployment? Enterprise AI fails not because models are bad but because deployment is hard. The labs that win will be the ones that understand not just how to build models but how to make them work inside actual businesses with actual data, actual compliance requirements, and actual users who need convincing. World Labs has this—their Marble product ships with clear workflows for gaming and VFX. Thinking Machines Lab does not, which is why former employees cite "lack of clarity on product direction."

Third, what is your capital strategy? The "Fund Cushion" will not last forever. The hyperscalers are cross-subsidizing AI with their core businesses; independent labs do not have this luxury. A lab with $3 billion in capital and a $500 million annual burn rate has 6 years to achieve escape velocity. That sounds like a long time until you realize that SSI is already two years in with no product in sight. The labs that survive will either find sustainable revenue before the runway ends, or find a strategic partner (government, hyperscaler, or acquirer) willing to provide indefinite support.

The Undercurrents

Beneath the funding announcements and product launches, deeper forces are shaping the landscape. Understanding them is essential to understanding which strategies will actually work.

The Ideological Schism

The talent movements of 2025-2026 are not merely strategic repositionings. They are ideological referendums.

Daniel Gross left SSI for Meta because he believed safety research requires "empirical feedback from real-world use." Sutskever believed that was "the slippery slope that had ruined OpenAI." They had reached, in the words of one person familiar with the discussions, "an impasse." This was not a disagreement about tactics; it was a disagreement about epistemology—about whether you can understand a system without deploying it.

Andi Peng watched Claude complete an eight-hour coding task autonomously. Her colleagues cheered. She sat with her arms crossed, troubled. Two months later, she left to co-found Humans&. This was not a career move; it was a vote about what AI should become.

Barret Zoph and multiple co-founders of the Thinking Machines Lab returned to OpenAI within days of each other. The stated reason was "lack of clarity on product direction." The unstated reason was that OpenAI offered something TML could not: the ability to ship at scale, to see your work reach hundreds of millions of users, to know that what you build matters immediately.

These movements reveal a fundamental schism in the research community. One faction believes safety and deployment can coexist—that you learn by shipping, that commercial pressure creates accountability, that impact requires reach. Another faction believes commercial pressure inevitably corrupts research—that the only path to genuine safety is insulation from market forces, that purity of mission requires purity of incentive. The labs in this analysis are not just competing for market share; they are competing to prove their theory of how AI development should work.

The Investor Insurance Game

Google gave SSI access to TPUs "previously reserved for internal use." Google also owns DeepMind. Google also invested in Anthropic. NVIDIA backed SSI, Humans&, and continues to sell to everyone. Why would these companies arm potential competitors?

Because they are not investing in companies. They are buying optionality.

If Sutskever cracks alignment before anyone else, Google has a relationship. If he doesn't, they've lost a rounding error on a balance sheet that measures compute investments in tens of billions. If Humans&'s collaboration thesis proves correct and the autonomous agent paradigm fails, NVIDIA has a stake in the winner. If agents succeed instead, NVIDIA sells the GPUs that power them.

This is not venture capital in the traditional sense—betting on a specific outcome and hoping it succeeds. This is portfolio construction at a civilizational scale, where the downside of missing the winner is so catastrophic that the rational strategy is to back everyone plausible and let the market sort it out.

The implication for labs is subtle but important: your investors may not need you to succeed. Google's TPU deal with SSI is valuable to Google whether SSI builds superintelligence or not—it creates a relationship, generates goodwill with Sutskever, and provides intelligence on what the most ambitious safety research looks like. The "patient capital" these labs have raised may be patient for reasons unrelated to their mission.

The Deployment-Safety Paradox

Every lab in this analysis is navigating the same unspoken tension: you cannot do safety research on systems you do not deploy, but deployment creates commercial pressure that corrupts safety research.

SSI chose purity. No products, no customers, no revenue, no deployment feedback. The risk is that they solve alignment for a system that does not exist, that their safety techniques prove irrelevant to the systems that actually get built, that they become a beautifully aligned dead end.

Anthropic chose compromise. Deploy with guardrails, commercialize with constraints, use revenue to fund research while accepting that revenue creates pressure to ship faster and be more capable, and worry less about edge cases. The risk is that the compromise becomes the identity, that the safety research becomes a marketing differentiator rather than a genuine constraint on development.

Humans& is making a different bet entirely. They are betting that the autonomous paradigm will fail—that enterprise customers will reject agents that work for eight hours unsupervised, that error rates will prove unacceptable, that regulation will constrain autonomy, that the market will correct toward collaboration before it rewards replacement. This is not just a product thesis; it is a timing thesis. Humans& is positioning for a world where Anthropic and OpenAI's autonomous agents hit a wall, and the market suddenly wants something different.

If they are right, their "human-centric" positioning becomes prescient. If they are wrong—if agents keep improving, if enterprises accept the error rates, if autonomy wins—Humans& becomes a philosophical curiosity that missed the actual curve.

The Language-First Heresy

Fei-Fei Li's manifesto on spatial intelligence contains a claim that is more radical than it appears: that language models are incomplete, that understanding the world requires understanding space, and that the path to general intelligence runs through 3D, not through text.

This is heresy in a field that has spent five years proving that scale plus text produces remarkable capabilities. The LLM-centric paradigm assumes that language is the universal interface—that if you can read and write well enough, you can reason about anything. Li argues that some forms of understanding are fundamentally spatial, that you cannot learn physics from text alone, and that embodied intelligence requires embodied training data.

World Labs' robotics ambitions are not a "nice expansion" from gaming and VFX. They may be the actual endgame. Gaming is the wedge—high volume, clear use cases, immediate revenue. But the strategic vision is that spatial intelligence becomes the foundation for robotics, autonomous vehicles, industrial simulation, and eventually any AI system that must interact with the physical world. If Li is right, World Labs is not building a niche product; it is building the missing half of artificial intelligence.

If she is wrong—if language models can learn physics from text, if simulation fidelity matters less than reasoning capability, if embodied AI ends up built on LLM foundations rather than spatial ones—then World Labs becomes an impressive content creation tool that never transcends its vertical.

The VC Time Horizon Trap

SSI has approximately $3 billion and roughly 20 employees. Even at aggressive researcher salaries and substantial compute costs, this suggests a decade or more of runway. But the runway is not the binding constraint. Investor patience is.

Venture capital funds have liquidity expectations of 7-10 years. The partners who approved SSI's investment need to return capital to their limited partners within a defined window. Around year 5 or 6, a subtle shift occurs: investors who were content to wait become anxious to see progress. Board seats become leverage. "Straight shot" pressure intensifies. Questions that were theoretical—"When will you have something to show?"—become urgent.

This is the trap that pure research labs face. The capital looks patient, but the structure is not. A lab that plans for 15 years of research funded by 7-year money will find, around year 5, that the money has opinions.

The sovereign pivot is not just a revenue option for SSI. It may be the only structural escape from VC time horizons. Government contracts operate on different timescales. Defense research programs run for decades. Intelligence agencies value capability over commercialization. A classified partnership does not require explaining to LPs why there is no product; it requires demonstrating capability to people who understand that some research cannot be rushed.

The Open Source Squeeze

Tinker runs on open-weight models: Llama, Qwen, and their successors. This is a feature—it gives users flexibility, avoids lock-in to any single model provider, and positions TML as neutral infrastructure. But it is also a vulnerability.

If open source continues to improve—and DeepSeek, Qwen 3, and Llama 4 suggest it will—the value of the fine-tuning infrastructure itself compresses. When the base models are free and increasingly capable, the willingness to pay for fine-tuning decreases. When fine-tuning techniques are published in papers and implemented in open libraries, the differentiation from DIY solutions shrinks.

TML is building a layer on top of a commoditized layer. The hyperscalers are coming from above with bundled offerings. Open source is coming from below with free alternatives. The strategic window for infrastructure providers is narrower than it appears, which is why the pivot to verticals—where domain expertise matters more than generic tooling—is not optional. It is existential.

The Strategic Playbooks

Diagnosis without a prescription is commentary. What follows are concrete strategic paths for each archetype—not generic advice, but specific moves that exploit the market's structural realities as they exist in 2026.

For the Sanctuary: The Controlled Descent

SSI's position is the most precarious and the most potentially valuable. The strategic challenge is not whether to eventually commercialize—Sutskever has already conceded that deployment will happen—but how to do so without abandoning the mission or triggering a talent exodus.

The licensing play. SSI's most valuable near-term asset is not a model but a methodology. Sutskever has already demonstrated willingness to collaborate on field-wide safety standards—he was among the signatories of the July 2025 position paper on chain-of-thought monitorability alongside researchers from OpenAI, Google DeepMind, and Anthropic. But SSI's internal research on scalable oversight, robust alignment, and reasoning verification could go further. If these techniques produce genuine breakthroughs, they become licensable to every other lab in the ecosystem. Anthropic's constitutional AI framework is not a product; it is an architecture that underpins products. SSI could occupy the same position one layer deeper—the safety infrastructure that commercial labs build upon. This generates revenue without product cycles, preserves research focus, and creates dependency relationships that increase SSI's strategic value.

The sovereign pivot. Governments are the only entities with longer time horizons than venture capitalists. The U.S. Department of Defense, intelligence agencies, and allied governments have an acute interest in AI systems that are both capable and verifiably aligned. SSI's explicit safety mandate positions it uniquely for sovereign partnerships that commercial labs cannot credibly pursue. A classified research contract does not require a consumer product. It requires demonstrated capability and trustworthiness—precisely what SSI claims to be building. The risk is capture; the benefit is an indefinite runway.

The milestone architecture. Pure research labs fail when investors lose faith in progress they cannot measure. SSI must construct a legible milestone architecture—not product launches, but demonstrated capabilities that validate the "straight shot" thesis. This might mean publishing alignment benchmarks that become industry standards, demonstrating reasoning capabilities that exceed commercial models on specific tasks, or releasing safety evaluation frameworks that other labs adopt. Each milestone extends the patience of capital without requiring commercialization.

The trigger conditions. Sutskever has acknowledged two scenarios that would force a pivot: timelines extending dramatically, or a capability breakthrough that demands real-world deployment. SSI should explicitly define these triggers and document them internally. At what burn rate does the board mandate revenue? At what capability threshold does deployment become ethically necessary? Ambiguity here is fatal. The labs that survive existential transitions are the ones that planned for them.

For the Infrastructure Provider: Vertical Depth Over Horizontal Breadth

Thinking Machines Lab's Tinker product is technically impressive and strategically vulnerable. Currently positioned as a horizontal fine-tuning API for researchers—with early adopters at Princeton, Stanford, Berkeley, and Redwood Research—Tinker abstracts away the complexity of distributed training while preserving algorithmic control. Andrej Karpathy praised its design tradeoffs, noting it retains "90% of algorithmic control while removing 90% of infrastructure pain." But researcher adoption does not automatically translate into enterprise revenue, and the hyperscalers are coming for this market. The path forward is not to compete with AWS on breadth but to pivot toward depth in domains where hyperscaler generality becomes a liability.

The vertical fortress. This requires a strategic pivot. Healthcare, financial services, and legal are not merely "industries"—they are regulatory regimes with compliance requirements that create structural barriers to entry. A fine-tuning platform optimized for HIPAA-compliant medical AI, with pre-built integrations to electronic health record systems, FDA submission frameworks, and clinical validation pipelines, is not competing with AWS Bedrock. It is competing with the 12-month implementation timeline that enterprises currently face when deploying AI in regulated environments. The same logic applies to financial services (SOX compliance, model risk management, explainability requirements) and legal (privilege preservation, citation verification, jurisdictional awareness). Tinker's current positioning as a general-purpose fine-tuning API for researchers is a steppingstone, not a destination. The endgame should be owning the fine-tuning infrastructure for one vertical, with compliance built into the architecture.

The deployment service model. Enterprise AI fails in deployment, not development. Surveys consistently show that 60-70% of AI pilots never reach production—not because the models fail, but because integration, governance, and change management fail. Thinking Machines Lab has operational expertise from building ChatGPT at scale. That expertise is more valuable as a service than as a product. The strategic move is to offer not just fine-tuning APIs but end-to-end deployment services: we will take your data, fine-tune the model, integrate it into your workflows, manage the governance requirements, and guarantee uptime. This is a services business, not a software business—but services businesses in complex domains command premium margins and create switching costs through institutional knowledge.

The co-development lock-in. Enterprise software creates lock-in through data gravity—once your data lives in Salesforce, moving it is painful. AI creates lock-in through workflow integration—once your processes depend on a fine-tuned model that understands your terminology, your edge cases, and your business logic, replacing it requires re-teaching a new system everything the old one learned. Thinking Machines Lab should pursue deep co-development partnerships with a small number of large enterprises, building models so tightly integrated into customer workflows that switching costs become prohibitive. Ten $50 million enterprise relationships are more defensible than a thousand $50,000 API customers.

The talent stabilization imperative. None of this works if the team keeps leaving. The January 2026 exodus revealed that Thinking Machines Lab had not solved the fundamental problem of researcher retention in a market where OpenAI and Meta can offer liquid equity and immediate deployment scale. The strategic response is to make the work itself the retention mechanism. Researchers stay when they are building things that ship, that matter, and that they could not build elsewhere. A vertical fortress strategy—where Thinking Machines Lab becomes the definitive AI infrastructure for, say, drug discovery—gives researchers a mission that OpenAI cannot offer: not "make the chatbot better," but "accelerate the development of life-saving therapies." Purpose retains talent that compensation alone cannot.

For the Collaboration Play: Finding the Coordination Tax

Humans& has the most philosophically interesting thesis and the most strategically ambiguous position. "Human-centric AI" is a differentiator only if it translates into workflows where human-AI coordination creates measurable, capturable value.

Identify the coordination tax. Every complex organization pays a "coordination tax"—the time, money, and error rate incurred when humans must align with each other and with information systems to execute multi-step processes. In most workflows, this tax is invisible because it is embedded in meetings, email chains, status updates, and the cognitive overhead of context-switching. Humans& must find workflows where the coordination tax is large, quantifiable, and reducible through AI mediation.

Consider clinical trial management: a Phase III trial involves hundreds of sites, thousands of patients, regulatory bodies across multiple jurisdictions, and a constant flow of adverse event reports, protocol amendments, and data queries. The coordination tax—measured in delayed enrollments, protocol deviations, and regulatory findings—runs into hundreds of millions of dollars per trial. An AI system that maintains persistent context across all stakeholders, remembers every protocol amendment, flags inconsistencies before they become violations, and coordinates between sites without requiring human intermediaries could reduce this tax by 20-30%. That is a billion-dollar value proposition for a single vertical.

Similar logic applies to M&A due diligence (coordinating across legal, financial, technical, and regulatory workstreams), complex construction projects (coordinating between architects, engineers, contractors, and inspectors), and enterprise software implementations (coordinating between vendors, integrators, and client teams). In each case, the value is not "better chat"—it is reduced coordination overhead in processes where misalignment is expensive.

The memory moat. Humans&'s technical emphasis on long-horizon memory and user understanding points to a genuine differentiator—but only if that memory becomes proprietary. A model that remembers your organization's terminology, your team's communication patterns, your project's history, and your stakeholders' preferences creates value that compounds over time. The strategic imperative is to make that memory non-portable. If the accumulated context can be exported to a competitor, it is not a moat. If switching to a competitor means re-teaching the system everything it learned over two years of deployment, that is a moat.

The anti-Copilot positioning. Microsoft's Copilot strategy is to embed AI into every surface of the productivity suite—Word, Excel, PowerPoint, Teams, and Outlook. This is a horizontal play that optimizes individual task completion. Humans& should position explicitly against this: not "AI in every app" but "AI across all apps." The value proposition is not helping you write a better email; it is maintaining coherence across the 50 emails, 12 meetings, and 6 documents that constitute a complex project. This requires deep integration, which means partnerships with enterprise software vendors who want an AI layer but do not want to build it themselves. Atlassian, Asana, Monday.com, and Notion are all potential partners for a "coordination layer" that sits above their individual applications.

The quantification imperative. Enterprise buyers do not purchase philosophy. They purchase ROI. Humans& must develop rigorous metrics for coordination value: meetings eliminated, decision latency reduced, error rates in handoffs, and time-to-alignment on complex decisions. These metrics must be measurable in pilots and demonstrable in case studies. "Human-centric AI" is a tagline. "37% reduction in project coordination overhead, validated across twelve enterprise deployments" is a sales tool.

For the Vertical Specialist: Platform Before Product

World Labs has the clearest strategic position and the most obvious path to expansion. The risk is not competition from generalists; it is failure to capitalize on the category-defining moment.

The platform acceleration. Marble is a product. The World API, launched in January 2026, marks the start of the transition to the platform—but the opportunity is far larger than the current implementation suggests. The AWS playbook is instructive: Amazon did not build every cloud application; it built the infrastructure that others used to build applications, and captured value through usage fees and ecosystem lock-in. World Labs must now aggressively expand the API's capabilities and developer ecosystem. This means SDKs in every major language, comprehensive documentation, developer relations teams at gaming conferences and robotics workshops, and a marketplace for third-party extensions. Every application built on Marble increases switching costs and creates demand for World Labs' continued development. The 120,000 free accounts registered in eight weeks represent latent platform demand—convert them into developers building on your infrastructure, not just users consuming your product.

The simulation expansion. Spatial intelligence is not just about generating pretty environments. It is about generating physically accurate environments where simulated agents can learn to interact with the world. This is the bridge to robotics, autonomous vehicles, and industrial automation—markets orders of magnitude larger than gaming and VFX. Tesla trains its self-driving systems in simulation. Boston Dynamics trains its robots in simulation. Every robotics company needs simulation environments, and most build them in-house because no adequate third-party solution exists. World Labs should position Marble not just as a creative tool but as the simulation infrastructure for embodied AI. This requires expanding from visual fidelity to physical fidelity—accurate physics, material properties, and interaction dynamics. It is a harder technical problem, but it unlocks a larger market.

The data flywheel. Every world generated in Marble is training data for the next version of Marble. Every user interaction—every edit, every expansion, every correction—teaches the model what humans want from generated environments. This is the data flywheel that generalist labs cannot replicate: they have internet text, but World Labs will have millions of human-curated 3D environments with explicit feedback on what works and what does not. The strategic imperative is to maximize the volume and diversity of this data by keeping free tiers generous, encouraging experimentation, and making it easy to share and remix generated worlds. Short-term revenue maximization (aggressive paywalls, restrictive licenses) sacrifices long-term data advantage.

The industrial vertical. The highest-value application of spatial intelligence is not entertainment; it is industrial digital twins. A pharmaceutical company that can simulate its entire manufacturing process—every reactor, every valve, every quality control checkpoint—can optimize operations, predict failures, and validate changes before implementing them in the physical world. A logistics company that can simulate its entire warehouse network can optimize layouts, test automation scenarios, and train workers in virtual environments. These are multi-million-dollar enterprise contracts with long sales cycles but extreme stickiness. World Labs should staff an enterprise sales team focused exclusively on industrial simulation, with pricing that reflects the value delivered (percentage of efficiency gains) rather than the cost of generation (per-world fees).

The Great Filtration

Strategy for the Post-Scaling AI Lab

The question facing new AI labs is not whether they want to make money—it's whether they control something scarce enough to command durable economic rents in a market where hyperscalers spend $600B annually to commoditize capabilities.

The labs that emerged based on talent and ambition will be tested on scarcity and execution. Some will achieve breakthroughs. Some will find niches. Some will get absorbed. Some will run out of money before they run out of ideas.

The Great Filtration

We are entering a period of consolidation in AI labs—what might be called the Great Filtration. The labs built on talent and ambition will be tested by scarcity and execution.

Some will achieve genuine breakthroughs and justify their valuations retroactively. Some will find vertical niches where they can build durable businesses away from the generalist competition. Some will be absorbed by hyperscalers who need the talent more than the technology. And some will simply run out of money before they run out of ideas.

The 5-Level Commercial Ambition Scale asks whether labs are trying to make money. The more important question is whether they can—whether they control something scarce enough, specific enough, and defensible enough to extract value from a market that is being commoditized at unprecedented speed.

The answer will determine which of today's AI labs become the Googles and Apples of the next era, and which become the footnotes.