Large Language Models (LLMs) have progressed by optimizing next-token prediction over massive corpora of public and licensed text. This approach has proven remarkably effective for learning linguistic structure, surface-level semantics, and broad factual knowledge. However, if the objective is genuine reasoning, abstraction, and intellectual progress, this paradigm is nearing its limits. The bottleneck is no longer scale, but the nature of the learning signal itself.

Most publicly available text data is retrospective, drawn from fixed past knowledge rather than active discovery. It reflects stabilized knowledge and polished conclusions rather than the frontier of discovery or the process by which understanding is formed. In compressing reasoning into final narratives, text removes the very signals required to learn how to reason - false starts, hypothesis generation, uncertainty, and revision. When models are trained primarily on such data, they internalize correlations in expression. But they do not internalize the generative mechanisms of thought. This makes them highly fluent within known distributions. Yet they are brittle when forced to extrapolate or reason under novel constraints.

Proprietary and enterprise data do not fundamentally resolve this limitation. While it can improve domain specificity and factual accuracy, it typically encodes decisions rather than the cognitive trajectories that led to those decisions. Organizational data is optimized for execution and efficiency, working to derive efficiencies and productivity, and sometimes, creativity too - but not exploration or epistemic openness. Training on it further reinforces existing priors instead of expanding the model’s internal hypothesis space.

The increasing use of model-generated data precipitates a profound systemic degradation. When LLMs train on their own outputs, they enter closed feedback loops in which errors are amplified, diversity is reduced, and novelty is diminished. From an information-theoretic perspective, this is a form of entropy reduction that converges toward the model’s existing approximations rather than toward external truth. What appears as progress through scale is, in reality, iterative self-compression.

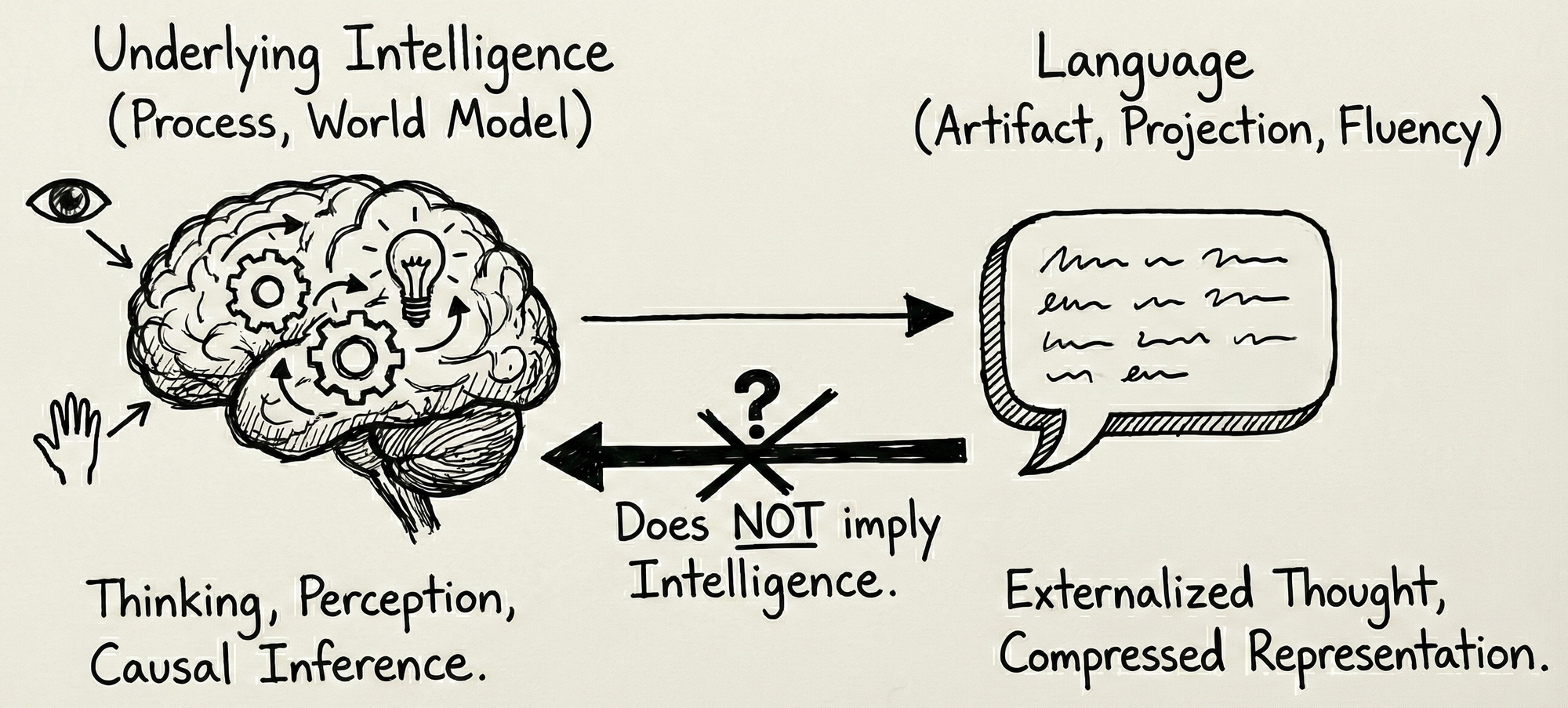

At a fundamental level, language is evidence of intelligence, not intelligence itself. It is an artifact, a projection, of underlying cognitive processes. The existence of language implies intelligence somewhere in the system that produced it, but the reverse is not true: producing language-like outputs does not imply the presence of intelligence. This distinction mirrors human development itself, where cognition clearly precedes language - infants reason, perceive causality, and act purposefully long before they speak.

Language externalizes thought. It allows reasoning, memory, and abstraction to be communicated and shared, yet it does not fully contain those processes. Much of intelligence operates beneath language through perception, world modeling, causal inference, planning, and action under uncertainty. Language is therefore a compressed representation of these processes, shaped for communication rather than for computation. In humans, language amplifies and structures existing cognition; it does not instantiate it.

Language is a projection of intelligence, not its substrate. Training models on language alone teaches them the statistical structure of communication, not the causal structure of the world that communication refers to. Fluency, in this sense, is not evidence of understanding, but of compression. Intelligence requires grounded world models, interaction, and the ability to reason under constraint; language merely externalizes the results of these processes.

This is where modern LLMs blur an important line. By training directly on linguistic artifacts, we conflate fluency with cognition. Models learn the patterns that emerge when intelligent agents communicate, but not the internal dynamics that generated those patterns. In doing so, they replicate the appearance of intelligence without inheriting its generative machinery, much like observing language without participating in the developmental processes that give rise to thought.

An analogy helps clarify the distinction. Motion blur in a photograph proves that something moved, but studying blur alone does not teach you physics. Similarly, language demonstrates that thinking occurred, but language alone does not encode the full causal structure of thought. It is an end product, not the process that produced it.

This is why scaling language data eventually saturates. Language reflects what humans choose to express, but not everything they reason through. It omits failed hypotheses, sensory grounding, tacit knowledge, and real-time interaction with the world. Training on language alone teaches models how intelligence sounds, not how it works.

For AI systems to move beyond imitation, language must be treated as one modality among many, an interface to intelligence rather than its substrate. True intelligence requires internal models grounded in perception, causality, constraints, and action. Language can then emerge naturally as a powerful abstraction layered on top of these mechanisms, rather than serving as a proxy for them.

True evolution, whether biological or intellectual, does not come from minimizing entropy everywhere. It emerges from allowing entropy to increase locally during exploration, while learning the structure of the dynamics that govern the entropy. In other words, progress emerges from controlled disorder paired with constraint discovery. What matters is exposing the system to environments where entropy is meaningful, where uncertainty arises from real constraints, causal interactions, and trade-offs. By observing how entropy evolves under action, the system can infer invariants, causal laws, and latent structure. That is understanding. Understanding is not the elimination of uncertainty; it is the ability to navigate, shape, and exploit it.

In current LLM training, this exploratory entropy is actively suppressed by optimization objectives that reward predictability and likelihood maximization over discovery and epistemic progress.

Grounding models in environments through multimodal learning and sensors is a necessary step forward – possibly, a ‘late fusion’ model could be the answer; however, we are not there yet. Environmental data introduces causality, temporal continuity, and constraints that text alone cannot provide. Sensors allow models to observe how the world changes over time and how actions produce consequences. Yet perception alone is insufficient. Sensors capture state, not intent or reasoning. Without agency systems that act, pursue goals, fail, and adapt, environmental data becomes another passive dataset rather than a source of understanding.

Reasoning emerges from closed-loop interaction. An intelligent system must form internal models of the world, act under uncertainty, observe the outcomes of those actions, and update its beliefs accordingly. This process cannot be learned solely from static observation. It requires environments, whether real or simulated, in which actions have irreversible consequences and trade-offs must be navigated.

At the core of these limitations lies a representation problem. Current language models learn high-dimensional vector representations optimized for likelihood maximization. Proximity in embedding space reflects statistical co-occurrence, not semantic or causal structure. Predicting the next word is a powerful compression mechanism, but compression is not true understanding. True understanding requires representations that encode causality, constraints, counterfactuals, and goals—structures that reflect how the world works, not just how it is described.

What is missing, therefore, is not simply more data, but a fundamentally different kind of data. Data that captures reasoning as a process rather than an outcome. Data that includes failure, exploration, and uncertainty. Data generated through interaction with constrained environments where decisions matter. Much of this data does not exist in naturally occurring text and cannot be obtained through scraping or licensing agreements. It must be deliberately created.

The next phase of AI progress is not primarily a data acquisition problem. It is a problem of data generation, representation learning, and training objectives. Progress will come from agentic systems trained through interaction rather than imitation, from synthetic and simulated environments that make reasoning unavoidable, and from human-AI collaboration that externalizes thought instead of compressing it away. Until these shifts occur, we will continue to build systems that are increasingly articulate yet fundamentally limited—mistaking fluency for intelligence, and scale for understanding.