The AI integration into the enterprise is not an incremental upgrade to the application portfolio; it represents a fundamental collision between two distinct architectural paradigms. For decades, enterprise technology has been anchored in deterministic systems, platforms engineered to produce predictable outputs from structured inputs, optimized for stability, auditability, and control. These systems of record encode business rules, preserve transactional truth, and enforce consistency at scale. However, AI, particularly, generative and agentic AI introduces a probabilistic layer that functions fundamentally differently from traditional deterministic software. Rather than following rigid instructions or linear execution, these systems reason and infer, producing outputs characterized by measurable uncertainty rather than absolute correctness. This non-deterministic behavior is fundamentally rooted in the transformer architecture, which operates on statistical distributions, and is further influenced by the inherent non-determinism found in GPU kernels.

The strategic challenge facing senior leadership is therefore not how to add AI to the existing stack, but how to design an operating model in which deterministic certainty can coexist with, and be amplified by, probabilistic intelligence. This is not merely a technical migration; it is an economic transformation. By architecting a system where intelligence is scalable and governable, the enterprise creates the capacity to decouple revenue growth from linear operating costs, reshaping how value is created and how margins are protected.

This realignment requires abandoning the notion of AI as a standalone vertical, innovation lab, or isolated capability. Instead, AI must be treated as a cross-cutting architectural concern, embedded across data, applications, workflows, and governance structures. From a tech strategy perspective, the constraining factor is increasingly not compute capacity or algorithmic sophistication, but the context. Even highly capable models degrade rapidly or do not produce the expected results when they are disconnected from enterprise knowledge, operating logic, and decision boundaries.

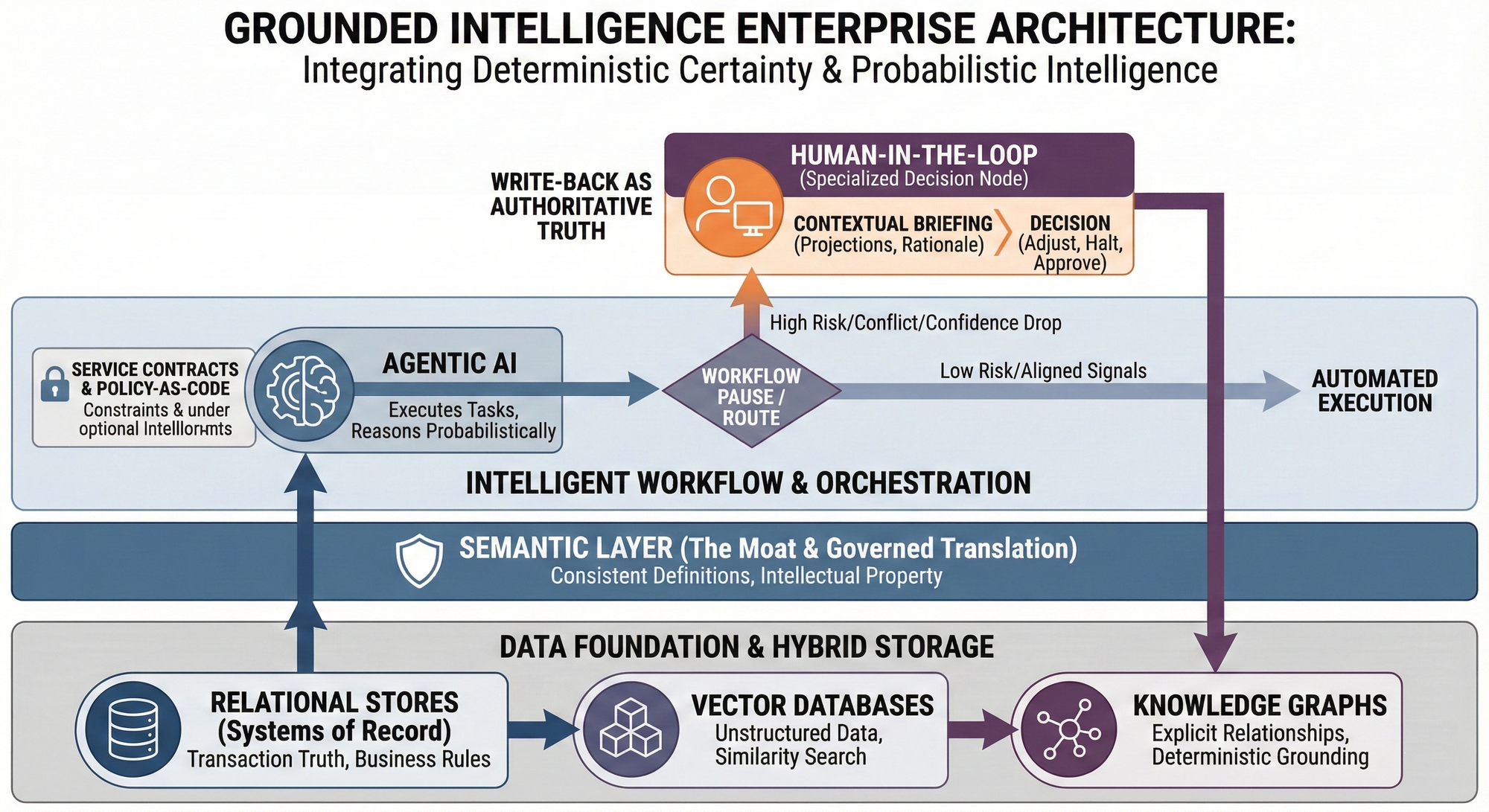

As a result, data architecture must evolve beyond its traditional role as a storage and reporting substrate. Data lakes and warehouses were designed to aggregate rows and columns to explain what happened. AI-enabled decision systems require architectures that can support reasoning about why an event occurred and what actions may follow, to derive an understanding. This necessitates a move from managing data primarily as volume to managing it as meaning. What follows is not an industry-standard blueprint, but a reference architecture that many enterprises are converging toward in practice.

In this model, a semantic layer provides a governed translation between operational schemas and business concepts, ensuring that entities such as “customer,” “margin,” or “risk exposure” have consistent, machine-interpretable definitions across systems. In an era where foundational models are rapidly becoming commoditized utilities, the enterprise’s only durable competitive advantage, its moat, is the proprietary structure of its own data (for this very reason, enterprises should identify all relevant and important data sources that they can use and also ensure data quality going forward – ignoring or an unidentified important data source can be detrimental). The semantic layer transforms raw data into defensible intellectual property that competitors cannot easily replicate.

Underneath this layer, traditional relational databases continue to serve as authoritative systems of record, while vector databases enable multi-dimensional similarity-based retrieval across unstructured information. Knowledge graphs provide deterministic grounding by encoding explicit relationships, constraints, and facts. Together, these components allow probabilistic reasoning to be anchored in verifiable enterprise truth, converting proprietary data from a passive archive into a computable strategic asset.

What This Changes in Practice: A Workflow Shift

1. Financial Operations: Customer Credit Approval

In a traditional enterprise system, customer credit decisions are rule-driven and batch-oriented. Thresholds are fixed, exceptions are escalated manually, and approvals are often made with incomplete or stale context. The process is predictable, but slow, brittle, and poorly suited to volatile market conditions.

In a grounded intelligence architecture, the system of record continues to enforce deterministic constraints such as regulatory limits, exposure caps, and contractual rules. What changes is the layer above it. An AI agent continuously synthesizes customer behavior, payment history, market conditions, and peer risk signals retrieved through the semantic layer and vector store.

When signals are aligned and risk is low, approvals proceed automatically within predefined boundaries. When signals conflict, such as a strong revenue opportunity paired with an emerging risk, the workflow does not fail or blindly proceed.

- The workflow pauses rather than escalates by default.

- The human credit officer is engaged not as an approver of paperwork, but as a specialized decision node.

- The officer is presented with context: projected upside, downside exposure, confidence intervals, and the rationale behind the recommendation.

The decision is made faster and with greater clarity. Once resolved, the outcome, approved or denied, is written back into the system as authoritative truth, improving both auditability and future decision quality.

The net effect is not simply efficiency, but better risk-adjusted growth at scale. This is what decoupling revenue growth from linear operating costs looks like in practice.

2. Industrial Operations: Advanced Manufacturing & Safety

A similar architectural shift occurs in advanced manufacturing and automotive environments, where errors translate directly into safety risks, yield loss, and brand damage.

Consider a high-precision manufacturing operation responsible for producing safety-critical components. In a traditional setup, quality deviations are handled reactively. Sensor data is logged, thresholds are monitored, and production is slowed or halted only when defect rates cross hard, predefined limits. The system is deterministic, but intervention often comes too late to prevent scrap or downstream impact.

Under a grounded intelligence architecture, deterministic systems of record still define non-negotiable constraints: safety tolerances, regulatory requirements, approved materials, and process limits. What changes is how early signals are interpreted.

An AI agent continuously correlates machine telemetry, environmental conditions, supplier batch data, and historical defect patterns using shared semantic definitions of concepts such as “yield,” “process drift,” and “critical variance.”

- When the system detects early indicators of deviation, signals that are statistically significant but not yet rule-breaking, it does not autonomously shut down the line.

- Instead, it generates a probabilistic assessment: the likelihood of yield loss, potential safety implications, and the cost trade-off between intervention and continuation.

- If signals suggest a safety-critical or brand-impacting risk, the workflow pauses.

At that point, a quality or production engineer is engaged as a decision node, not an emergency responder. They receive a concise briefing that includes inferred root causes, projected outcomes, and recommended actions within approved limits. The human decision, adjust, reroute, or halt is then executed through the system of record and logged with full traceability.

The result is not reckless or blind automation, but earlier intervention, reduced waste, faster recovery, and preserved human authority in environments where mistakes are unacceptable.

With this contextual foundation in place, organizations can begin to move from insight generation toward controlled action. Agentic AI marks a qualitative shift in capability. Unlike generative systems that produce content for humans to interpret, agentic systems are designed to execute tasks, invoke APIs, modify records, and trigger workflows. This shift materially changes the operational and risk profile of the technology stack, as software systems become active participants in business processes rather than decision-support tools.

In such an environment, the role of an AI Center of Excellence (CoE) must expand beyond coordination and experimentation. It becomes an architectural authority responsible for defining how humans and autonomous systems interact. This includes establishing interaction standards for how digital agents authenticate, access resources, communicate intent, and relinquish control. Treating AI agents as non-human identities, subject to role-based access controls and explicit permission boundaries, allows autonomy to be constrained by design rather than policy aspiration.

A central construct in this architecture is the service contract for the agent. Each agent operates within a clearly defined mandate that governs what it may observe, recommend, and execute. An agent may be permitted to draft actions but not finalize them, optimize within predefined limits but not alter strategic thresholds. These constraints must be enforced at the infrastructure level, allowing deterministic systems to function as guardrails around probabilistic reasoning.

Equally important is the redefinition of the human-in-the-loop. In mature AI-enabled operations, the human is not merely an exception handler invoked after failure, but a specialized decision node embedded within the workflow. This requires stateful orchestration capable of pausing long-running processes, preserving context, and routing decisions to human experts when confidence drops, risk increases, or ethical thresholds are approached, thus creating a symbiotic partnership between humans and AI.

The Cost of Getting This Wrong (and the Cost of Doing It Right)

It is important to be explicit about tradeoffs. Architectures like this are not free.

Building and governing semantic layers takes time, cross-functional alignment, and sustained investment. Agent orchestration introduces latency and operational complexity. Poorly designed human-in-the-loop mechanisms can slow execution rather than accelerate it. Overly rigid guardrails can suppress value just as easily as overly permissive ones can create risk.

Most failures in enterprise AI do not occur because the models are weak, but because organizations underestimate the operating model change required to support them. Teams attempt to bolt agentic systems onto legacy workflows, treat governance as an afterthought, or delegate architectural authority to vendors. The result is either stalled adoption or uncontrolled automation.

The discipline described here is not about maximizing autonomy; it is about earning autonomy safely.

As AI capabilities approach operational execution, governance must evolve accordingly. Responsible AI cannot be addressed solely through principles or post-hoc review. It must be embedded into system design through policy-as-code, access controls, and explainability mechanisms that are integrated directly into the inference and orchestration layers. In this way, regulatory compliance and ethical safeguards emerge as architectural properties rather than after-the-fact controls.

From a business operations perspective, the ultimate measure of success is not model accuracy, but organizational adaptability. High-impact AI use cases deliver sustainable value only when operating models allow for process collapse, the compression of time, handoffs, and organizational distance between insight and execution. This is not merely an efficiency play; it is a mechanism to outpace market volatility.

Finally, strategic control over the AI ecosystem becomes a leadership responsibility - a commitment is certainly required here for success. Vendor platforms, model providers, and tooling choices must be evaluated not only for their capability, but also for their interoperability, transparency, and long-term flexibility. Architectures that preserve ownership of data, semantics, and decision logic provide resilience as technologies evolve.

Viewed this way, enterprise architecture reasserts its relevance, not as documentation, but as the mechanism through which intelligence becomes operable at scale. Systems of record continue to provide stability, systems of intelligence introduce adaptability, and governance structures ensure trust. When these elements are intentionally designed to work together, AI becomes neither a fragile experiment nor an uncontrollable force, but a durable, governed capability embedded directly into the enterprise operating model.