In November 2025, Mercedes-Benz announced a strategic reversal. After 3 years of attempting comprehensive transformation—allocating 75% of investment to luxury segments and targeting 14% operating margins through disciplined positioning—the company abandoned the strategy. Mercedes had achieved 4.8% Q3 operating margins, performance so poor that continuing became unsustainable despite billions invested and fundamental organizational restructuring.

BMW watched this unfold from a different position. While Mercedes attempted a radical transformation, BMW maintained a balanced approach across segments. The company achieved 5.2% Q3 2025 operating margins—still below historical double-digit levels, still within challenging 5-7% guidance, but better than Mercedes’ 4.8%. BMW continued investing in its Neue Klasse electric vehicle platform without the panic that marked Mercedes’ strategic whiplash. Sales grew 8.7% globally in Q3, with strong 25% growth in the US market. The company maintains positive free cash flow projected above €2.5 billion for the year.

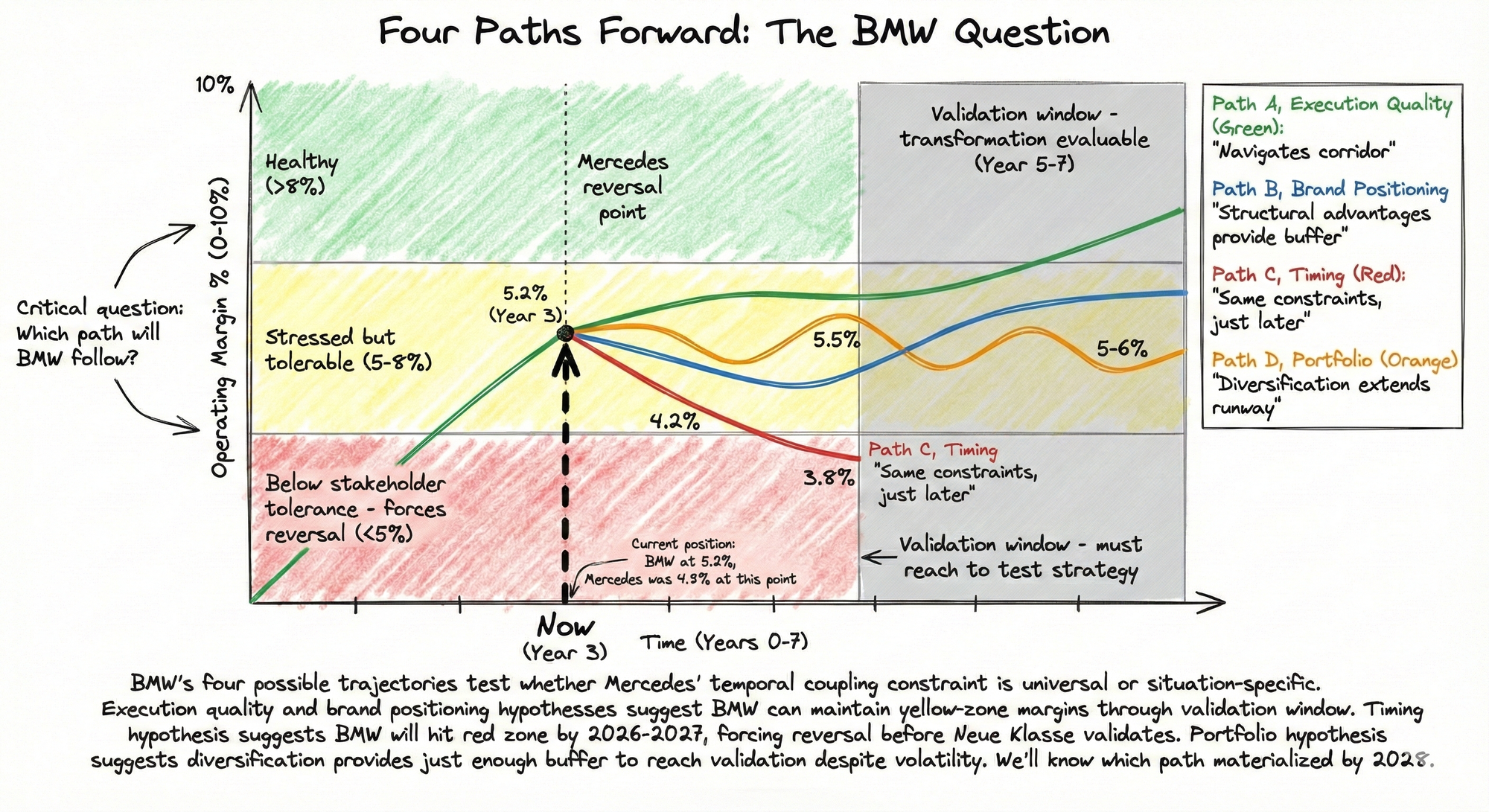

This raises the fundamental question: Does BMW’s relative outperformance prove that the strategic corridor remains navigable with better execution, or does it merely demonstrate that BMW hasn’t yet hit the wall Mercedes encountered? Put differently, is BMW executing the sustainable path Mercedes failed to find, or is BMW simply 3 years behind in confronting the same impossible constraints?

The answer matters immensely. Mercedes’ experiment demonstrated that validation timelines and financial runways are temporally coupled—when transformation requires 5-7 years to validate but stakeholder patience expires after 3 years of compressed margins, certain theoretically optimal strategies become impossible regardless of quality. The question for BMW: Is this constraint universal, or can structural advantages create exceptions?

The Performance Gap That Demands Explanation

The margin difference between BMW and Mercedes appears modest—40 basis points in Q3, 20 basis points for 9 months. But this represents meaningful outperformance when both companies face similar competitive pressures from Tesla's software-defined architecture, Chinese manufacturers' cost advantages, and rapid product cycles, and emerging autonomous platform economics.

Four hypotheses merit examination, each implying radically different strategic lessons.

The execution quality hypothesis: BMW simply executed better within the same constraints. More disciplined cost management—BMW CFO Walter Mertl noted the company avoided Mercedes’ mistake of overcommitting to luxury repositioning before validating market acceptance. Superior operational efficiency—BMW’s Munich and Dingolfing plants maintained 87% capacity utilization versus Mercedes’ Sindelfingen at 73%. Smarter product portfolio decisions—BMW maintained E-Class competitor 5-Series volumes while Mercedes de-emphasized equivalent segments. Under this view, the strategic corridor is narrow but navigable. Mercedes failed due to execution shortcomings, not because the transformation was impossible. Every incumbent has hope through skilled management.

The brand positioning hypothesis: BMW’s “Freude am Fahren” identity, built on driving dynamics, creates more defensible positioning than Mercedes’ luxury-comfort-status proposition. The buyer who chose the BMW 3-Series specifically for steering feel and chassis balance—who tracks the car on weekends, who cares about lateral g-forces and throttle response—represents fundamentally different psychology than the Mercedes buyer optimizing for comfortable transportation with status signaling. This enthusiast segment is explicitly resistant to autonomous platform substitution because the value proposition is driving, not being driven. When autonomous platforms offer equivalent transportation at 60% lower cost, the utilitarian Mercedes buyer switches. The BMW enthusiast doesn’t, because transportation optimization was never the point. Under this interpretation, only companies serving explicitly autonomous-resistant segments can successfully navigate disruption.

The timing hypothesis: BMW hasn’t encountered the constraints yet. Mercedes attempted a radical transformation requiring sustained margin compression, discovered that the financial runway was insufficient to meet the validation timeline, and reversed course after 3 years. BMW hasn’t yet attempted a transformation of this magnitude—Neue Klasse is a gradual evolution, not a radical repositioning. BMW hasn’t tested the limits. The company’s better margins don’t demonstrate superior execution; rather, they reflect that BMW hasn’t yet reached the crisis point. Under this interpretation, BMW will hit the same wall Mercedes encountered within 2-3 years as Neue Klasse investment intensifies and competitive pressures mount.

The portfolio hypothesis: BMW’s product mix provides the flexibility Mercedes lacked. M performance vehicles appeal to driving enthusiasts explicitly resistant to autonomous substitution—the M3 buyer wants to drive, full stop. The motorcycle business provides meaningful diversification—BMW Motorrad delivered 210,000 units in 2024 with 7.9% EBIT margins, providing a buffer when automotive margins compress. The brand portfolio, including MINI (targeting younger buyers with lower price points and distinct brand associations) and Rolls-Royce (serving the ultra-luxury segment with structural pricing power), offers strategic maneuvering options. Mercedes’ more concentrated lineup lacked these buffers. Under this interpretation, portfolio diversification provides a meaningful advantage but doesn’t solve the fundamental temporal coupling constraint—it merely provides a longer runway before encountering the same wall.

Distinguishing among these hypotheses determines BMW’s optimal strategy. The Neue Klasse platform sits at the center of this strategic question. If execution quality explains outperformance, maintain the current approach while learning from Mercedes’ mistakes. If brand positioning explains it, double down on driving dynamics differentiation. If timing explains it, prepare for encountering similar constraints. If the portfolio explains it, leverage diversification while recognizing that it merely delays rather than solves the fundamental challenge.

The Neue Klasse Gamble: Architecture Versus Time

BMW’s Neue Klasse strategy represents an €18.2 billion bet—€9.1 billion for retooling the Debrecen and Munich plants, €6.3 billion for sixth-generation battery development promising 30% faster charging and 40-50% cost reduction, and €2.8 billion for software partnerships with Qualcomm and other platform providers. The first production model, the iX3 SAV, launches from Debrecen in late 2025. A sporty sedan will follow from Munich in 2026. By 2027, BMW projects forty new or updated models across all drivetrain variants.

This differs fundamentally from Mercedes’ approach. Rather than exiting vulnerable segments to focus on protected luxury positions, BMW is betting that architectural innovation enables it to position competitively across all segments simultaneously. The Neue Klasse platform must compete against Tesla’s integrated fifth-generation architecture, Chinese manufacturers’ cost-optimized platforms, and autonomous service economics—all while maintaining brand differentiation around driving dynamics and generating 5-7% margins sufficient to fund multi-year investment cycles.

This is extraordinarily demanding. BMW is attempting to develop electric platforms competitive with Tesla and Chinese manufacturers, maintain internal combustion engine excellence for markets where electric transition proceeds slowly, invest in autonomous driving technology to avoid platform irrelevance if service models capture significant share, preserve driving dynamics differentiation justifying premium pricing, and achieve all this at margins well below historical levels but sufficient to sustain transformation. Mercedes initially attempted a similar comprehensive approach, then pivoted to a radical luxury transformation when gradual evolution proved financially unsustainable. That pivot failed after 3 years. BMW is still executing the gradual, comprehensive approach Mercedes abandoned.

Three interpretations are possible.

First, validated sustainable path: Mercedes panicked prematurely. BMW’s steadier approach demonstrates that a gradual, comprehensive transformation can be executed within financial constraints if management maintains discipline and avoids overreacting to competitive pressures. Neue Klasse investment will generate sufficient competitive advantage to sustain 5%+ margins long-term, making transformation self-funding over an extended timeline.

Second, delayed recognition: BMW is executing the same strategy that Mercedes initially attempted, only to recognize it was financially unsustainable. Neue Klasse investment will eventually force the same choice—accept sustained sub-5% margins to complete transformation, or reverse course and abandon committed investments. BMW simply hasn’t reached a crisis point yet.

Third, different game: BMW’s structural positioning creates a genuinely different competitive situation, making gradual transformation feasible where Mercedes’ approach was not.

The evidence available in Q3 2025 doesn’t definitively resolve these interpretations. BMW’s margins remain under pressure—5.2% versus 9.8% in 2023, guided to 5-6% for the full year after revising downward from initial 5-7% guidance. Mertl cited tariff impacts of 1.5 percentage points, a 13.7% decline in China volume, and €400 million in dealer support payments. But margins haven’t collapsed below 4% as Mercedes experienced. Sales grew 8.7% globally. Electrified vehicle sales increased 8%. Free cash flow remains positive. BMW is under pressure but not in crisis—yet.

BMW’s Structural Advantages—And Their Limits

BMW possesses potential advantages that might alter the temporal coupling calculation. The brand positioning around “Freude am Fahren” serves segments explicitly resistant to autonomous substitution. The enthusiast who chose BMW for steering feel represents fundamentally different buyer psychology than the practical premium transportation optimizer. When autonomous platforms offer equivalent transportation at lower cost, the transportation optimizer switches. The driving enthusiast doesn’t, because optimization was never the point.

Portfolio diversification provides buffers Mercedes lacked. M performance vehicles serve enthusiasts willing to pay a premium for the driving experience. The motorcycle business generates 7.9% margins, serving different customer segments with different economics. MINI targets younger buyers with lower price points and different brand associations. Rolls-Royce serves the ultra-luxury segment with structural pricing power independent of mainstream premium dynamics. This diversification doesn’t address fundamental constraints, but it provides a longer runway and greater strategic flexibility.

The technology-open approach, maintaining internal combustion, electric, and hydrogen (from 2028), offers hedging against scenario uncertainty. Mercedes’ radical luxury pivot bet heavily on a specific future—autonomous disruption intense enough to fragment the market into protected luxury positions and commoditized volume segments. BMW’s balanced approach performs adequately across multiple scenarios. If the electric transition accelerates, Neue Klasse positions competitively. If the transition proceeds slowly, maintained ICE excellence preserves market share. If autonomous platforms capture a significant share, driving dynamics differentiation protects the enthusiast segment while a diversified portfolio provides buffers.

The modular Neue Klasse rollout differs from Mercedes’ concentrated transformation. Rather than comprehensive portfolio restructuring, BMW is attempting to reach a protected steady state quickly by gradually introducing architecture across segments over 5 years. This approach validates market acceptance incrementally—if early Neue Klasse models succeed, continue rollout; if they struggle, adjust before overcommitting. Mercedes’ concentrated approach created an all-or-nothing bet requiring sustained margin compression before any validation occurred.

But these advantages may be insufficient if the underlying constraint is universal. Consider the China challenge—both companies face 13-14% volume declines in a market that historically accounts for 25-30% of premium volumes. If Chinese manufacturers have achieved sustainable cost advantages through vertical integration, battery technology leadership, government subsidies, and domestic supply chains that foreign manufacturers cannot match, then BMW’s architectural innovation cannot offset permanent market share loss. A 10% volume decline at constant margins is manageable. A 10% volume decline combined with ongoing margin pressure creates compounding stress that killed Mercedes’ transformation. Whether China pressure is cyclical (addressable through Neue Klasse products optimized for the Chinese market) or structural (reflecting permanent competitive disadvantage) determines whether BMW’s advantages matter or merely postpone the inevitable encounter with the same constraints Mercedes faced.

The Critical Question and Five Strategic Options

The question BMW leadership must answer: can the Neue Klasse transformation reach an evaluable steady state within the timeframe in which 5-7% margins can be sustained? If the transformation requires 5-7 years to validate and margins drop below 5% within 2-3 years, BMW faces the same temporal mismatch that Mercedes discovered. If margins sustain or transformation validates more quickly, the strategy may prove viable.

Five strategic options merit consideration, each addressing the temporal coupling constraint in a different way.

First, maintain the current trajectory with extended tolerance for sub-optimal margins. This bets gradual comprehensive transformation can be executed within financial constraints if management maintains discipline over an extended timeline. It requires accepting 5-7% margins for 5-10 years while the transformation validates, resisting stakeholder pressure, and expecting a return to double-digit profitability. Success depends on whether Neue Klasse generates enough competitive advantage to sustain these margins over the validation period. This is BMW’s current path.

Second, accelerate Neue Klasse rollout to compress the validation timeline. Rather than a gradual five-year rollout, reach an evaluable steady state more quickly through concentrated investment. This requires accepting even lower margins near-term—possibly dropping below 5% temporarily—but shortens the uncertainty period. The risk is that a compressed timeline might be even less sustainable than a gradual approach, forcing a reversal before transformation completes, as with Mercedes. This addresses timing risk but increases financial stress risk.

Third, pursue modular transformation validatable within shorter timeframes. Rather than a comprehensive platform transformation across all segments, prioritize the highest-confidence elements that can be validated within 3-year windows that align with the probable financial runway. Focus Neue Klasse initially on segments where competitive advantage is clearest—perhaps electric M performance vehicles where driving dynamics differentiation is strongest—while maintaining existing platforms elsewhere. Sacrificing comprehensiveness for faster validation reduces all-or-nothing risk. This is a partial hedge against the temporal coupling constraint.

Fourth, optimize for the current competitive environment rather than transforming for an uncertain future. Mercedes’ reversal can be seen as recognition that attempting transformation creates worse outcomes than competing effectively today. Maintain current portfolio balance, compete with existing platforms, and make incremental improvements rather than a bet-the-company transformation. This accepts vulnerability if disruption accelerates, but avoids transformation costs and organizational damage from potential reversal. It is a conservative approach when transformation feasibility is uncertain.

Fifth, leverage structural advantages through differentiation rather than transformation. Rather than viewing Mercedes’ failure as a general warning, interpret it as specific to Mercedes’ situation. BMW’s brand positioning, portfolio diversification, and technology-open approach create a genuinely different competitive situation. Double down on differentiating characteristics—make Neue Klasse the platform for enthusiast-oriented premium EVs, directly addressing the segment most resistant to autonomous substitution. This maximizes structural advantages rather than attempting comprehensive transformation.

The choice among these options cannot be made with confidence, given the available evidence. BMW’s forty-basis-point margin advantage might demonstrate superior execution of sustainable strategy, or might simply reflect that the company hasn’t encountered binding constraints yet. Neue Klasse might generate sufficient competitive advantage to validate gradual transformation, or might prove inadequate against Chinese cost structures and autonomous platform economics.

Watch BMW—The Experiment Is Running

We’ll know by 2028. If BMW maintains margins above 5% through 2027-2028 while Neue Klasse investment is validated by observable market acceptance and sustainable unit economics, it proves that skilled execution, combined with structural advantages, can navigate temporal coupling. The strategic corridor is narrow but navigable. Every incumbent facing similar dynamics has reason for hope. Strategic transformation under uncertainty remains extraordinarily difficult but not impossible.

If BMW’s margins deteriorate below 5% before Neue Klasse validates—if the company faces in 2027 or 2028 the same stakeholder pressure Mercedes encountered in 2025, forcing a similar strategic reversal—it confirms that the temporal coupling constraint is universal rather than situation-specific. The implication would be stark: certain theoretically optimal transformation strategies are practically impossible for public companies facing quarterly performance pressure, regardless of strategic insight quality, execution capability, brand positioning, or portfolio diversification. The slow-motion collapse of traditional premium automotive business models is no longer pessimistic speculation but an observable reality.

Either outcome resolves the fundamental question: is strategic transformation under uncertainty merely difficult, or genuinely impossible for public companies facing quarterly pressures? Mercedes provided expensive empirical evidence that a transformation requiring 5-7 years of validation cannot be sustained when stakeholder patience expires after 3 years. BMW is testing whether structural advantages—brand positioning serving autonomous-resistant segments, portfolio diversification providing buffers, technology-open approach offering flexibility, modular rollout enabling incremental validation—create sufficient exceptions to make transformation viable.

The experiment is running. The stakes are clear. The implications extend beyond automotive to every industry where optimal long-term positioning requires accepting extended periods of sub-optimal financial performance. We’re watching strategic planning theory collide with organizational reality in real time, and the collision will resolve within thirty-six months. BMW either navigates where Mercedes failed, proving the constraint is situation-specific rather than universal, or encounters the same wall, confirming that certain correct strategies are impossible when validation requirements exceed available financial runway.

Watch carefully. We’ll have the answer soon.