There is a question that haunts every corporate strategy meeting, every venture capital pitch, and every policy discussion about technology: why has the most broadly diffused set of technologies in human history produced the most concentrated distribution of economic returns?

The internet is everywhere. Smartphones are ubiquitous. Cloud computing has democratized infrastructure. And yet, the value generated by these technologies flows to a vanishingly small number of firms, clustered in a handful of geographic locations, operating in a narrow set of industries. This is not a bug in the system. It is the system.

The Co-Invention Imperative

To understand this paradox, recognize that "technology adoption" is a misnomer. Technologies are not simply adopted; they are co-invented. The steam engine, electric dynamo, and internet did not deliver economic value in isolation. Value emerges only when a general-purpose technology is combined with complementary investments in applications, business processes, organizational structures, and new products.

This insight, developed by economists Timothy Bresnahan, Shane Greenstein, and Manuel Trajtenberg over three decades of research, has profound implications. If technology adoption were simply a matter of purchasing and deploying new tools, we would expect a relatively normal distribution of returns: most firms would capture modest benefits, some would do better, and some would do worse. Instead, we observe something radically different—a power-law distribution in which a tiny fraction of firms captures almost all the value.

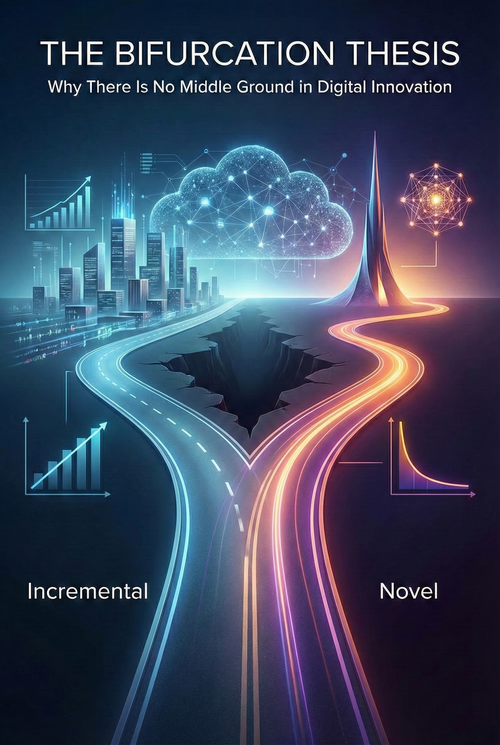

The explanation lies in two fundamentally different co-invention regimes, each with distinct economic laws. The most important strategic insight of the digital age may be this: there is no viable path between them.

Two Economies, One Technology

The Incremental Economy is characterized by firms using digital tools to enhance existing operations. A bank builds a mobile app. A retailer adds e-commerce. A newspaper publishes online. These are low-risk, moderate-cost investments that yield predictable, bounded returns. The value created is proportional to the firm's pre-existing assets—its customer base, its brand, its physical infrastructure.

This economy is geographically dispersed, industrially broad, and sustaining. It reinforces existing competitive hierarchies rather than disrupting them. A regional bank with a good mobile app is still a regional bank. A local newspaper with a website is still competing against the same advertisers and readers as before.

The Novel Economy operates on entirely different principles. Here, firms create products, services, and business models that did not previously exist. Netflix did not digitize Blockbuster; it invented streaming entertainment. Uber did not improve taxi dispatch; it created on-demand mobility. Google did not build a better directory; it invented the ad auction.

The novel economy is characterized by high costs, extreme uncertainty, and—crucially—returns that follow a power law distribution. Most novel co-inventions fail completely. The few that succeed capture value that dwarfs the entire incremental economy combined. Research consistently shows that the top 1% of app publishers generate 94% of App Store revenue. In gaming, the top-ranked app earns 100 times as much as the 200th-ranked app. This is not a gentle slope; it is a cliff.

The Disappearing Middle

Here, the strategic implications become acute. The defining feature of the digital age is not the existence of these two economies; some version of this duality has always existed. It is the hollowing out of the middle ground between them.

Consider the cost structure. Incremental co-invention requires purchasing off-the-shelf software, hiring consultants, and making minor workflow adjustments. Novel co-invention demands years of R&D investment, organizational transformation, the destruction of existing competencies, and the recruitment of specialized talent concentrated in specific geographic hubs. There is no moderate version of novel co-invention. You cannot half-build a platform. You cannot partially create a network effect.

Consider the uncertainty profile. Incremental co-invention carries idiosyncratic risk—will our implementation work? This risk is manageable and insurable. Novel co-invention carries systemic risk—will anyone want this? Will the ecosystem support it? This risk is uninsurable and requires a portfolio approach where most bets fail.

Consider the return distribution. Incremental returns are linear: a 10% investment yields about a 15% improvement. Novel returns are convex: most yield nothing, but successes yield 100x or 1000x.

The implication is stark. A firm cannot position itself for "moderate innovation with moderate returns." The fixed costs of genuine novelty have risen to the point that half-measures are no longer economically efficient. You must choose to be an excellent incrementalist, extracting maximum value from your existing assets through digital efficiency, or a committed novelist, accepting that most experiments will fail in pursuit of transformative returns.

The middle ground, once occupied by firms doing both, has become a strategic dead zone.

The Organizational DNA Problem

If the strategic imperative is clear, why do so many firms remain trapped in the dead zone? The answer lies in organizational DNA.

The capabilities required for incremental excellence are antithetical to those for novel success. Incrementalism rewards efficiency, predictability, and the optimization of existing processes. Novelty rewards exploration, tolerance for failure, and willingness to cannibalize existing revenue streams. These are not different points on a spectrum; they are different species of organization.

The Netflix-Blockbuster case study is instructive not because Blockbuster ignored the internet—it launched Blockbuster Online in 2004—but because Blockbuster's organizational structure could not escape its own logic. Every investment in digital had to justify itself against the existing store network. Every innovation that threatened late fees ($800 million annually) faced internal resistance. The organization was optimized for a world that was disappearing, and optimization is the enemy of transformation.

Contrast this with Netflix's willingness to cannibalize its profitable DVD-by-mail business to pursue streaming, even when this meant confusing customers and angering shareholders. Or Disney's decision to pull content from Netflix—sacrificing immediate licensing revenue—to build Disney+. These were not incremental decisions. They were organizational rewirings that only became possible when leadership recognized that the alternative was extinction.

The New York Times offers a particularly instructive example because newspapers faced perhaps the most brutal collision between incremental and novel logic. Most newspapers treated the web as a distribution channel for existing content—classic incremental co-invention. They replicated print online, assumed advertising would follow eyeballs, and kept newsrooms operating as they always had. The result was catastrophic: print advertising revenue collapsed from $60 billion to $20 billion over 15 years, while the novel value of digital media was captured by aggregators who invented entirely new ways to organize and target information.

The Times eventually succeeded by recognizing that digital required novel co-invention, not just digital distribution. The metered paywall introduced in 2011 was not merely a pricing decision—it required reinventing the product itself, building data science capabilities, developing customer lifecycle management expertise, and fundamentally shifting organizational culture from "audience maximization" to "subscriber value." Today, the Times has over 7.6 million digital subscribers. Most of its newspaper peers, trapped in incremental logic, have disappeared or diminished to irrelevance.

The lesson is counterintuitive: resource availability does not determine success in novel co-invention. Blockbuster had more resources than Netflix. GE invested billions in its Predix industrial internet platform before abandoning it. The New York Times did not have more resources than the Chicago Tribune or Los Angeles Times; it had a different organizational DNA. The determining factor is organizational capacity for transformation, which is rarely present in firms optimized for incremental excellence.

The Geography of Novelty

One might expect that digital technology, which makes remote collaboration easy, would disperse innovation activity. The opposite has occurred.

Research by economist Enrico Moretti documents that the ten largest cities account for 69-77% of inventors in key technology fields—and this concentration has increased since 1971. Despite Zoom, despite Slack, despite the entire apparatus of remote work, high-tech inventors are more geographically clustered today than they were when long-distance phone calls were expensive, and email did not exist.

Why? Because novel co-invention requires resources that cannot be digitized: thick labor markets for specialized talent, tacit knowledge that spreads through informal networks, and the cognitive diversity that comes from the collision of technical and domain expertise.

Silicon Valley did not become the center of innovation because of its weather. It became the center because it accumulated the specialized talent—engineers who understand CDN architecture, product managers who know how to engineer viral loops, designers who can invent new interaction paradigms—that novel co-invention requires. This talent cluster creates a self-reinforcing dynamic: ambitious people move there because opportunities exist, and opportunities exist because ambitious people are there.

The implication for firms outside these clusters is uncomfortable. Incremental co-invention can happen anywhere; it follows the geography of existing business activity. Novel co-invention clusters because it must. A firm attempting transformative innovation from a location without access to thick, specialized labor markets faces a structural disadvantage that remote-work tools cannot fully overcome.

Network Effects and the Lock-In of Novelty

The power law distribution of novel returns is not merely a statistical curiosity. It reflects a specific mechanism: network effects.

Research from NFX, a venture firm that has studied this extensively, found that about 70% of value creation in technology since 1994 has come from companies with network effects. These effects are almost exclusively products of novel co-invention. You cannot incrementally build a network effect by improving an existing product; you must create something new that becomes more valuable as more people use it.

Once established, network effects create formidable barriers. A competitor cannot lure users away without first building an equal or larger network, a bootstrapping problem that becomes harder as the incumbent grows. This explains why novel co-invention tends toward winner-take-all outcomes: the first firm to achieve critical mass in a network-effect business often captures the entire market.

Airbnb illustrates the dynamic. As more hosts listed properties, travelers found greater variety; as more travelers booked, hosts found better returns. This two-sided network effect created liquidity that competitors could not match. A new entrant would need to simultaneously attract hosts and travelers in sufficient density to be useful—a cold-start problem that Airbnb has already solved.

The strategic implication is that novel co-invention is not just high-risk/high-reward. It is temporally bounded. There is a window during which network effects can be established; once that window closes, the market locks in. Missing the window does not mean capturing smaller returns; it means capturing no returns at all.

The AI Acceleration

Everything described above is about to intensify.

Artificial intelligence meets the criteria for a general-purpose technology: pervasiveness across sectors, inherent improvement potential, and innovational complementarities. Because AI is about creating replicable intelligence, a capability relevant to nearly every economic activity, it may be the most general-purpose technology of all.

The emerging bifurcation in AI mirrors the pattern we have seen before.

Incremental AI, such as copilot-style tools that improve individual productivity, will diffuse broadly, creating modest efficiency gains across the economy. Every knowledge worker will eventually have AI assistance for drafting emails, summarizing documents, and automating routine tasks. These gains are real but bounded; they make existing workers more efficient without transforming what work means.

Novel AI, such as autonomous agents, new discovery processes, and applications we cannot yet imagine, will concentrate value in the few firms that achieve breakthrough applications. The difference is categorical. Incremental AI asks: how can we do what we already do, faster? Novel AI asks: what becomes possible that was impossible before? The firms that answer the second question will capture value that dwarfs the efficiency gains from the first.

But the concentration may be more extreme than anything seen before. The capital requirements for frontier AI are staggering: OpenAI raised $40 billion in 2025; Anthropic raised $3.5 billion. The compute infrastructure required for training and inference creates natural monopolies. The data advantages of incumbents compound over time. Unlike the web era, where a garage startup could challenge incumbents with clever code, frontier AI development requires resources that only a few organizations can muster.

Moreover, research on the productivity J-curve suggests that AI adoption will follow a pattern familiar from previous GPTs: an initial period of productivity decline as organizations invest in complementary changes (process redesign, workforce retraining, organizational restructuring) before benefits materialize. Recent Census Bureau research confirms this pattern at the firm level—AI deployment leads to measurably negative effects in the short run, followed by growth over time.

Critically, this J-curve is not uniform. Firms that have already completed digital transformation, with the data infrastructure, technical talent, and organizational flexibility, will navigate this curve more easily. Their existing digital foundations provide the substrate on which AI capabilities can be built. Those still struggling with basic digitization will find the AI transition even more wrenching; they must digitize and AI-enable simultaneously, compressing two transformations into one.

Strategic Implications

What does this mean for strategy?

For incumbents, the central challenge is recognizing that organizational inertia poses a greater threat than resource constraints. The choice is binary: either build genuine capacity for novel co-invention, accepting that this requires organizational transformation, not just investment, or commit fully to incremental excellence, extracting maximum value from existing assets while accepting that transformative growth is off the table. The dead zone, attempting both within the same organizational structure, is where value goes to die.

For entrants, the window for novel co-invention remains open but increasingly demands capital-intensive approaches, especially in AI. Strategies that worked in the web and mobile eras, such as starting small, iterating quickly, and achieving product-market fit before scaling, may be insufficient when the cost of frontier experimentation runs to billions of dollars. Platform independence, focus on specific novel use cases, and building network effects before incumbents respond remain viable strategies, but the margin for error has narrowed.

For investors, the implication is that the barbell strategy is not just preferable but necessary. Investments in incremental co-invention will yield steady, modest returns proportional to the underlying business. Investments in novel co-invention will mostly fail but occasionally produce returns that dwarf entire portfolios. The middle, moderate level of innovation for moderate returns does not exist in sufficient quantity to build a strategy around.

For policymakers, understanding these dynamics is essential for effective innovation policy. Policies supporting technology diffusion, such as subsidies for adoption and digital literacy programs, address only the incremental economy. Policies that foster the new economy, support entrepreneurship, develop specialized talent, enable geographic clustering, and ensure competitive platform markets require an entirely different toolkit.

The Bifurcation Endures

The paradox we started with—universal technology diffusion producing concentrated returns—is not a transitional phase. It is the equilibrium state of digital economics.

The forces driving bifurcation are structural: the distinct cost profiles, uncertainty characteristics, and return distributions of incremental versus novel co-invention create sorting mechanisms that push firms toward one pole or the other. The middle ground has been hollowed out not by market failure but by market logic. Rising fixed costs of genuine novelty, increasing returns to network effects, and geographic clustering of specialized talent all reinforce the same dynamic: go big or go home.

This creates a peculiar strategic landscape. At one pole, many firms extract modest value through incremental co-invention, competing on operational excellence rather than transformative innovation. Their returns are stable but bounded, their competitive positions defensible but not dominant. At the other pole, a few firms capture astronomical returns through novel co-invention, building network effects and platform positions that compound over time. Between them: a wasteland.

For strategists, the uncomfortable truth is that comfort is not an option. The choice between incremental and novel paths cannot be deferred, hedged, or averaged. The firm that attempts to be moderately innovative, to take moderate risks for moderate returns, will find itself outcompeted by incrementalists on efficiency and by novelists on transformation. This is not a failure of imagination or execution; it is a structural impossibility.

The appropriate response depends on honest self-assessment. Most firms, the vast majority, should embrace incremental excellence and stop pretending otherwise. There is dignity and profit in being the best at what you already do, enhanced by digital tools. The error is not in choosing incrementalism; it is in choosing incrementalism while speaking the language of disruption and investing in innovation theater rather than genuine transformation.

For the few firms with the organizational DNA, capital access, talent base, and risk tolerance to pursue novel co-invention, the path is clearer but more brutal. Accept that most bets will fail, build for network effects and platform positions, locate where specialized talent clusters exist, and commit resources at a scale that forecloses retreat.

The bifurcation is not a problem to be solved. It is a reality to be navigated. And navigation begins with recognizing where you stand—and choosing, decisively, where you intend to go.

Innovation Regime Decision Framework

A structured diagnostic for leadership teams assessing their innovation position

Diagnostic Assessment

A. Where Does Your Value Come From?

B. How Does Your Organization Actually Work?

C. What Is Your Relationship to Uncertainty?

Interpreting Your Position

Committed Incrementalist

- >90% revenue from established products

- ROI-based evaluation dominates

- Failed projects damage careers

- No significant cannibalization history

- <3 year investment horizons

This is a valid and potentially excellent position. The error is not being here; the error is pretending you're somewhere else.

- Stop funding innovation theater

- Invest aggressively in operational excellence

- Monitor novel threats but don't pretend you can respond in kind

- If transformation becomes existential, recognize it requires rupture

Committed Novelist

- Significant revenue from products <5 years old

- Portfolio-based evaluation with failure tolerance

- Network effects or platform dynamics drive value

- History of deliberate cannibalization

- Long investment horizons

You have the organizational capacity for novel co-invention. The challenge is maintaining it as you scale.

- Protect cultural and structural elements that enable novelty

- Resist gravitational pull toward incrementalism as revenue grows

- Maintain tolerance for failure even as stakeholder expectations rise

- Continue investing in talent density and specialized labor markets

Unstable Hybrid

- Mixed signals across diagnostic questions

- Innovation initiatives evaluated on incremental criteria

- Stated tolerance for failure, revealed intolerance

- Transformation language without cannibalization history

- Best people leaving or disengaged

You are in the unstable middle. Organizational forces are pushing you toward one pole whether you choose or not. The longer you remain here, the more resources you waste.

- Force an explicit choice: incremental excellence OR structural separation

- If choosing incremental: stop the theater, redirect to operational excellence

- If choosing novelty: create genuinely separate structures (see Part III)

- Do not attempt to "balance" within the same organizational unit

What Crossing Requires

Structural Separation

- Physically and organizationally separate unit

- Different P&L, leadership, and talent

- Different evaluation criteria (not ROI-based)

- Explicit permission to cannibalize parent

- Protection from parent's optimization pressure

- A lab attached to the core business

- A venture arm that co-invests with VCs

- An accelerator that runs cohorts

- An innovation team reporting to the CFO

Rupture

- Organization-wide transformation of incentives and culture

- Active suppression of the old logic

- Willingness to sacrifice near-term performance

- Complete leadership alignment

- Existential clarity (usually a near-death experience)

- Adding transformation goals to existing incentives

- Running change management programs

- Announcing a pivot while preserving all commitments

- Maintaining core business as usual

Part IV: The Honest Conversation

Questions to confront as a leadership team: