Recommend reading these previous posts.

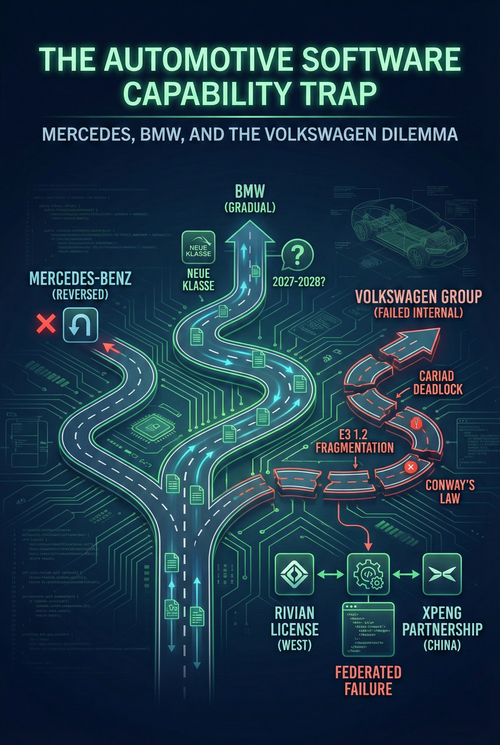

Mercedes-Benz attempted a radical transformation and collapsed after 3 years. BMW is taking a gradual approach, with margins compressed to 5.2%. Neue Klasse investment continues, with outcomes uncertain until 2027-2028. Volkswagen Group found a third path: it failed before either approach could be tried.

The company spent 5 years and billions of euros building a software capability that never worked, watched its financial runway disappear, and then paid $5.8 billion to license technology from an American startup that had sold cars for just 3 years. By Q3 2025, Volkswagen achieved 2.3% operating margins—half of Mercedes' 4.8%, less than half of BMW's 5.2%—while CARIAD, its software subsidiary, continues posting €1.5 billion in annual losses even after the strategic pivot.

Here's what makes Volkswagen's failure different from Mercedes' reversal: Mercedes discovered that validation timelines exceed financial runways. The company attempted the right strategy and ran out of time to prove it worked. BMW is testing whether structural advantages—brand positioning, portfolio diversification, modular rollout—extend the runway enough. We won't know until 2027-2028. But Volkswagen learned something worse: internal capability development might be impossible, no matter the runway, when organizational architecture conflicts with software architecture.

CARIAD represents the most expensive failed transformation in modern automotive history—not because the strategy was wrong, but because the company tried to compress a ten-year development timeline into a 5-year financial window while operating within an organizational structure that systematically prevented the capability from being built.

The Capability Trap

The temporal coupling trap describes the mismatch between validation timelines and financial runways. Mercedes discovered that a 5-to-7-year transformation cannot be sustained when stakeholders force a reversal after 3 years of compressed margins. But Volkswagen's failure reveals a more fundamental constraint: the capability development timeline can exceed both the validation timeline and the combined financial runway.

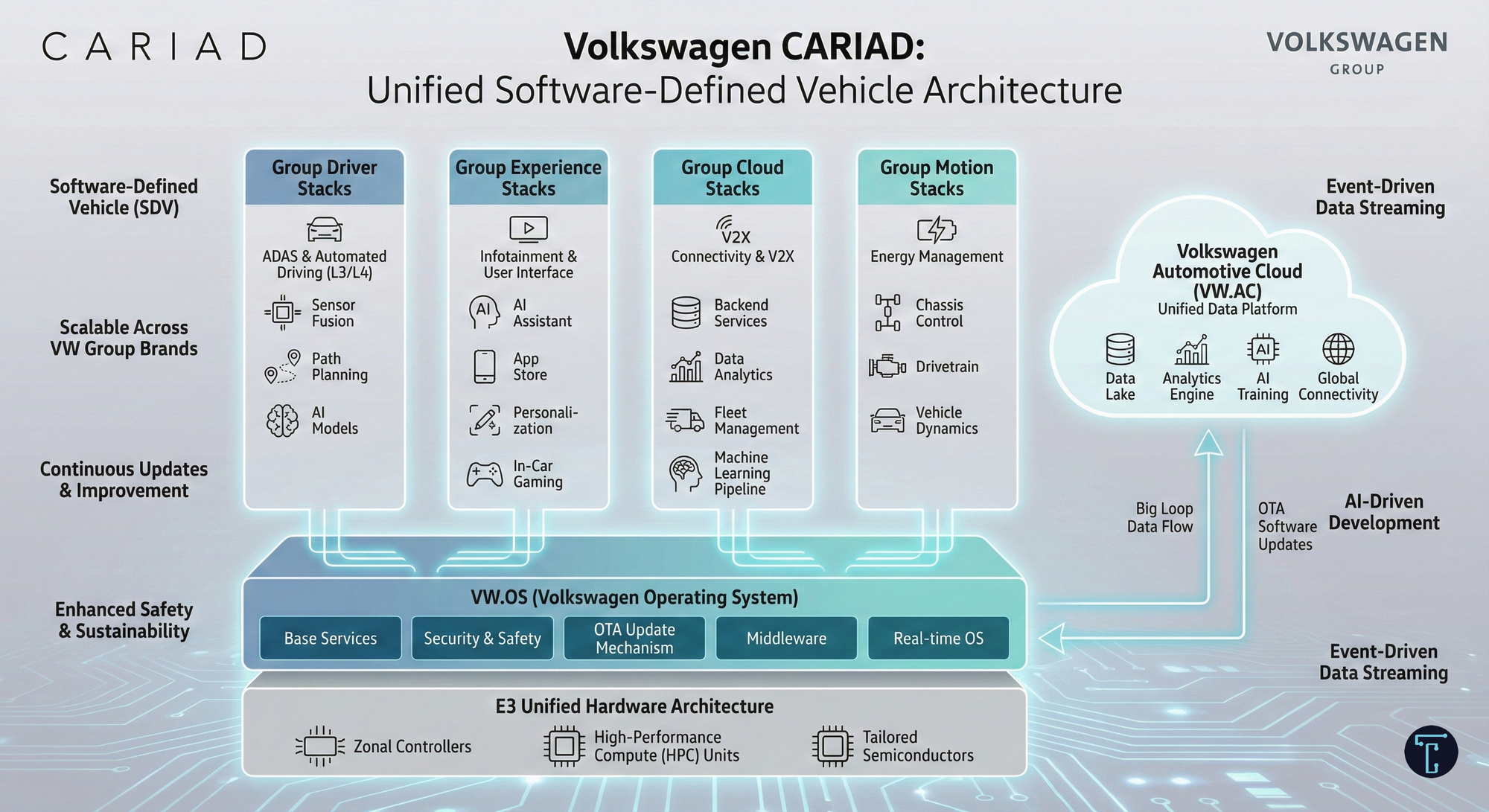

Consider the mathematics. Building a unified software stack to run across 12 brands—Volkswagen, Audi, Porsche, Bentley, Lamborghini, Skoda, SEAT, CUPRA, and commercial vehicle divisions—while achieving Level 4 autonomy readiness and maintaining over-the-air update capability requires architectural decisions that affect thousands of hardware interfaces, millions of lines of code, and supplier relationships spanning decades. Tesla developed this capability over 15 years of vertical integration, starting from a clean sheet. Volkswagen attempted it in 5 years while maintaining legacy platforms, meeting divergent brand requirements, and operating within German labor frameworks that emphasize consensus and job security.

The company flooded the problem with resources. CARIAD grew to 6,000 employees through aggressive hiring and internal transfers. Investment exceeded €2 billion annually. Herbert Diess, the CEO who championed the initiative, declared that software would become Volkswagen's core competency and that the company would increase in-house software development from 10% to 60% by 2025. The belief was that scale, Volkswagen's traditional advantage, would translate to software velocity.

This violated a fundamental principle of software development. Brooks's Law observes that adding manpower to a late software project makes it later. Software scales through architectural elegance, not headcount. Volkswagen's approach—hiring thousands of engineers without clear integration plans, forcing collaboration between hardware-oriented automotive veterans and agile-trained tech workers, and imposing German labor practices on Silicon Valley development methodologies—created organizational entropy instead of capability accumulation. The 6,000 employees produced less output than leaner teams at competitors because organizational friction consumed effort that should have gone to generating capability.

The Architecture of Failure

The failure of CARIAD is not abstract—it is encoded in the collapse of three software architectures that consumed years of development time while delivering nothing viable.

E3 1.1, designed for the MEB platform powering the ID.3 and ID.4, launched in 2020 in an infamously unfinished state. Early vehicles suffered severe latency, infotainment crashes, and complete system failures, requiring physical recalls rather than over-the-air fixes. Instead of establishing Volkswagen as a technology leader, E3 1.1 reinforced the narrative that legacy automakers cannot build software. Worse, CARIAD spent years patching this architecture—diverting resources from future development to maintain a system that should never have shipped.

E3 1.2 represented the critical failure. This architecture was intended for the Premium Platform Electric, underpinning Volkswagen's most important profit generators: the Porsche Macan EV and Audi Q6 e-tron. The strategic logic was sound—generate high margins from premium vehicles to fund continued software investment. But E3 1.2 was not a clean-sheet design. It tried to integrate legacy Audi electronics, Porsche performance modules, and new CARIAD code. The conflicting requirements of Audi, focused on luxury integration, and Porsche, focused on latency and dynamics, created an architectural deadlock. The result was an 18-month delay that cost Volkswagen billions in revenue at the peak of the EV adoption curve and forced Porsche to keep selling aging internal combustion models.

E3 2.0, the unified operating system that was supposed to justify everything, slipped from 2025 to 2026, then to 2028, then to 2029. By mid-2024, it was clear the validation timeline was extending indefinitely, while the financial runway was already exhausted. The billions invested generated no deployable asset. This is the cruel mathematics of capability failure: sunk costs do not create options; they only create obligations to maintain systems that were never competitive.

Conway's Law Wins

Here's the insight that distinguishes Volkswagen's failure from Mercedes' or BMW's challenges: Volkswagen's failure was not purely technical—it was sociotechnical. Conway's Law observes that organizations design systems that mirror their communication structures. Volkswagen Group is not a unitary company but a federation of powerful, semi-autonomous kingdoms: Wolfsburg, Ingolstadt, Zuffenhausen. CARIAD was established to strip software authority from these brands and centralize it. But the brands retained control over hardware and vehicle requirements. CARIAD engineers found themselves serving two masters, required to build a unified stack while satisfying bespoke and divergent brand specifications.

The result was predictable. Because the organization was fragmented, the software architecture became fragmented. E3 1.2 became a Frankenstein system, patching together modules from different brand requirements instead of emerging from coherent design principles. When Porsche recognized that CARIAD's delays threatened its electrification targets, the brand began rebellion maneuvers—seeking to decouple its software destiny from the central unit, further fragmenting resources and creating competing development tracks within the same corporate structure.

Put differently, the federated structure that enabled Volkswagen to manage 12 brands across global markets could not deliver the unified software system required to compete in software-defined vehicles. The organizational architecture that generates current competitive advantage systematically prevents the development of the capabilities required for future competition.

This is why Volkswagen's situation is categorically different from Mercedes or BMW. Mercedes attempted a transformation and discovered stakeholder patience expires before the strategy validates. BMW is testing whether structural advantages extend the runway. Volkswagen discovered that organizational structure can make transformation impossible, regardless of patience or runway. Conway's Law creates a binding constraint that money cannot solve.

The $5.8 Billion Admission

In late 2024, Volkswagen acknowledged the impossibility of the mathematics by announcing a 50-50 joint venture with Rivian, committing up to $5.8 billion to license the American startup's zonal software architecture. This partnership deserves precise interpretation: Volkswagen is paying billions to license technology from a company that began delivering vehicles in 2021, that has produced fewer than 200,000 units lifetime, and that remains unprofitable. Rivian's software exists and works. Volkswagen does not. That asymmetry justified writing off years of internal development and ceding control over the digital architecture of future vehicles.

At the same time, Volkswagen acknowledged that a single global software stack is impossible, given the speed of the Chinese market. The XPeng partnership and the CARIZON joint venture with Horizon Robotics create a parallel development track—China Electrical Architecture—completely decoupled from Western operations. This creates a two-speed Volkswagen: Chinese operations technologically divorced from global operations, each dependent on external partners rather than internal capability.

The appointment of Peter Bosch as CARIAD CEO in 2023 marked the transition from visionary to liquidator. His mandate was not shipping E3 2.0 but stopping the bleeding—cutting 2,000 jobs, divesting non-core assets, shifting CARIAD from developer to integrator. Herbert Diess's centralized software vision was dismantled. Software authority returned to brands. External partnerships replaced internal development. CARIAD's role is now to coordinate technology that it does not create.

The company now operates what might be called a federated failure: licensing Rivian's software stack for Western markets, partnering with XPeng for China, and maintaining CARIAD as a coordination layer between external architectures and internal manufacturing. This is not a strategy in progress; it is a surrender with extra steps.

Three Experiments Running

The German premium automotive industry is now running three simultaneous experiments on temporal coupling constraints.

Mercedes' experiment concluded in November 2025: radical transformation requiring 5-7 years of validation cannot survive 3 years of stakeholder pressure at 4.8% margins. The company reversed, bearing both failed transformation costs and the competitive vulnerabilities it tried to escape.

BMW's experiment continues: gradual evolution through Neue Klasse, maintaining 5.2% margins while testing whether structural advantages—brand positioning around driving dynamics, portfolio diversification, technology-open approach—create enough runway extension. We will know by 2027-2028 whether BMW navigates the trap or encounters the same wall Mercedes hit.

Volkswagen's experiment is different in kind. The company is not testing whether a transformation strategy can survive stakeholder pressure. It already failed that test. Volkswagen is now testing whether external integration can succeed where internal development failed, and whether the organizational architecture that prevented building capability also prevents integrating capability developed elsewhere.

The strategic pivot creates new temporal coupling challenges. Volkswagen must graft Rivian's zonal architecture, designed for a vertically integrated, clean-sheet startup, onto the complex, fragmented industrial machinery of twelve brands, hundreds of global suppliers, and manufacturing facilities spanning continents. There is a significant risk that Rivian's software will encounter the same rejections from Volkswagen's legacy hardware suppliers—Bosch, Continental, Valeo—that E3 1.2 experienced. Reports already suggest friction at the interface between Rivian's code and Volkswagen's metal.

The target for the first Rivian-based Volkswagen is 2027, the same year BMW's Neue Klasse experiment should begin generating validating evidence. Delays are already rumored, pushing volume production toward 2029 or 2030. If this occurs, Volkswagen will have lost nearly a decade of software competitiveness, from CARIAD's 2020 founding through delayed Rivian integration, while paying both the sunk costs of failed internal development and the ongoing licensing costs of external dependency.

Meanwhile, the demoralized CARIAD workforce, employees who joined to build Volkswagen's future and are now relegated to coordinating other companies' technology, must execute this integration. Top talent has departed. Those remaining face layoffs or marginalization. Volkswagen relies on teams it has betrayed to handle the critical interface between external software and internal manufacturing. This is not a minor operational risk.

The Lesson

The binding constraint at Volkswagen was not a lack of strategic insight. Diess correctly identified that software would capture future profit pools. It was not financial resources; Volkswagen spent billions. It was not commitment; the company reorganized fundamentally around the software vision. The binding constraint was organizational architecture incompatible with the capability being developed. Conway's Law won.

This carries implications beyond automotive. When capability development requires architectural coherence that conflicts with the existing organizational structure, transformation may be impossible regardless of investment, commitment, or timeline. The company cannot buy its way out of Conway's Law. It cannot hire its way out. It cannot will its way out.

Volkswagen's 2.3% operating margin is not a transition cost on the path to transformation. It is the structural position of a company that failed to transform, now dependent on external technology while bearing the costs of failed internal development. The strategic question is no longer whether Volkswagen can build software capability. That question is answered. The question is whether Volkswagen can integrate external capability faster than competitors extend their advantages, and whether the federated organizational structure that prevented internal development will also prevent external integration.

Watch all three experiments. If BMW's Neue Klasse validates by 2028 while maintaining margins above 5%, it proves that structural advantages can navigate temporal coupling—the constraint is situation-specific, not universal. If BMW hits the same wall Mercedes encountered, it confirms the constraint is inescapable for public companies facing quarterly pressure. And if Volkswagen's Rivian integration succeeds by 2027, it suggests that buying capability can substitute for internal development when organizational architecture prevents it. If the integration fails or delays extend toward 2030, Volkswagen will have demonstrated that neither building nor buying solves Conway's Law.

The experiments are running. Unlike Mercedes's concluded reversal, both BMW and Volkswagen remain mid-test with outcomes uncertain. But the nature of uncertainty differs. BMW is testing whether the right strategy can survive long enough to be validated. Volkswagen is testing whether any strategy, build or buy, can overcome organizational architecture that rejected both approaches.

The company that watched its competitor fail found a way to do worse.