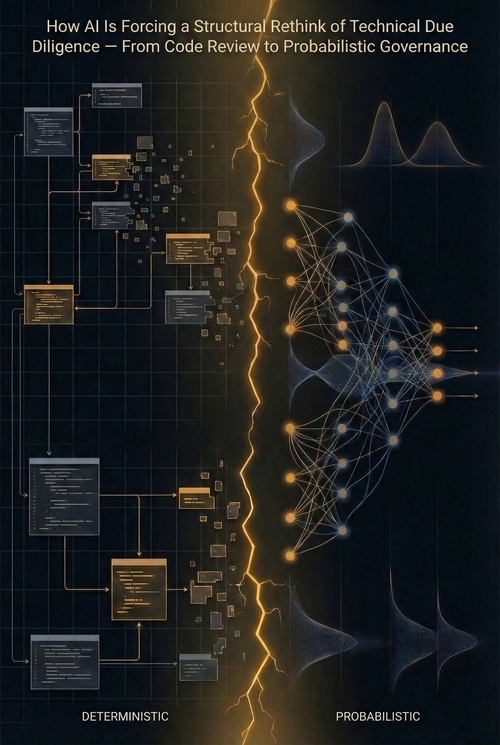

How AI Is Forcing a Structural Rethink of Technical Due Diligence — From Code Review to Probabilistic Governance

For nearly two decades, technical due diligence operated on a comforting premise: software is deterministic. You could read the code, trace an input through a series of logic gates, predict the output, and render judgment on the quality of what lay between. The audit — whether for a $20 million Series B or a $2 billion acquisition — was an exercise in structural inspection. Was the architecture scalable? Was the code maintainable? Did the API contracts hold? If you answered those questions with reasonable rigor, you had done your job.

That premise is now broken.

The integration of AI into the core of enterprise technology stacks—not at the periphery, not as a chatbot on a help desk, but as the reasoning layer that governs operational logic, financial allocation, and, for physical AI, human safety—has introduced a category shift in what it means to audit a technology company. The object under examination has changed in kind, not just in degree. The same input can now produce different outputs. The system's behaviour is an emergent property of billions of parameters that no human fully comprehends. With autonomous agents, the system is no longer just generating text; it is taking consequential actions in the world through probabilistic inference.

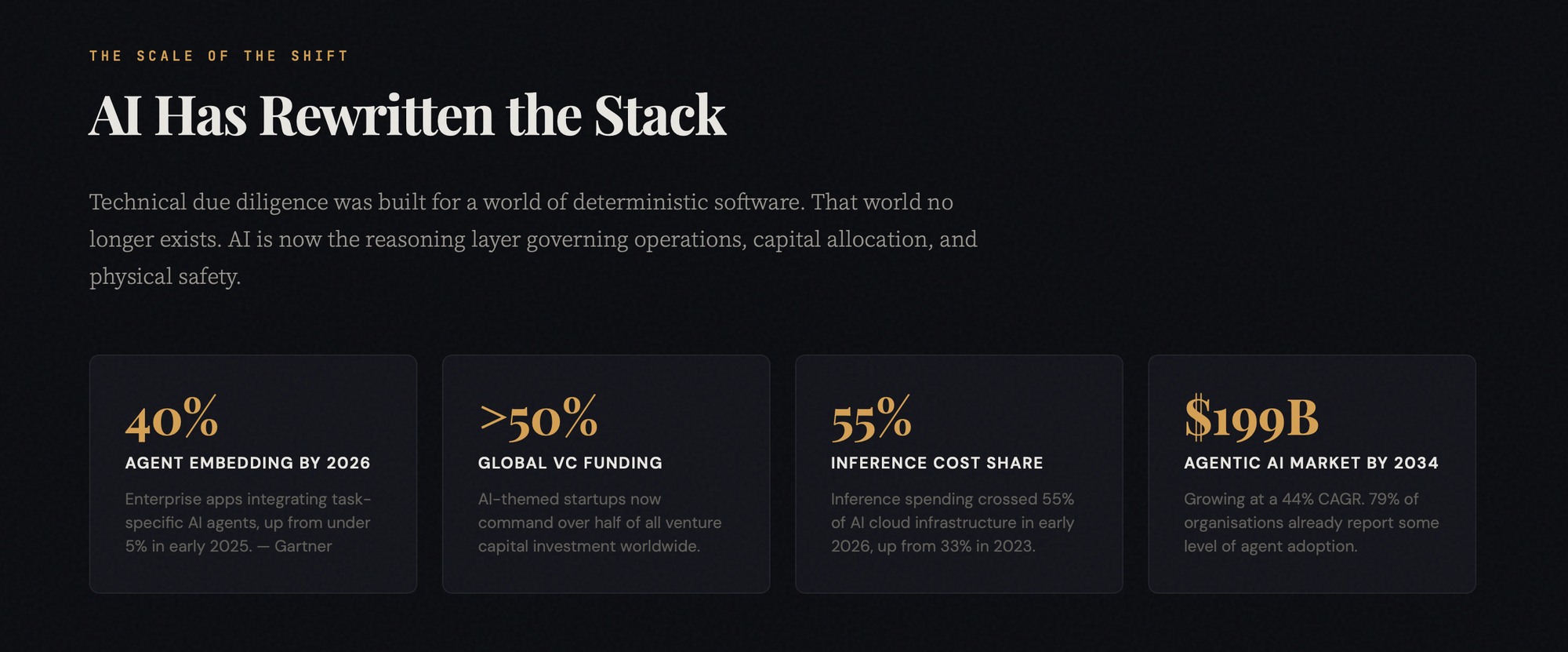

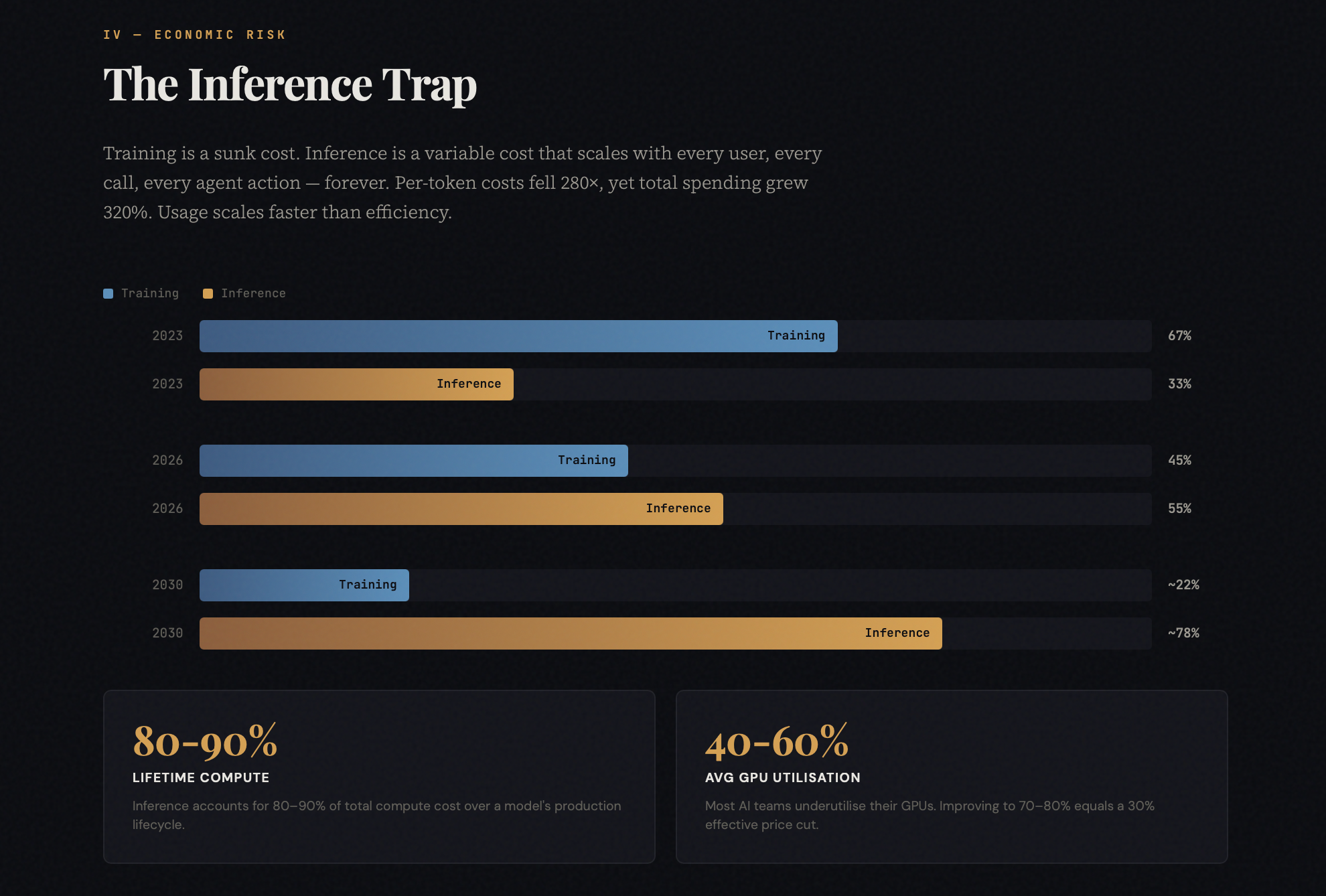

The implications for investors, acquirers, and boards are profound. Gartner projects that 40% of enterprise applications will embed task-specific AI agents by the end of 2026, up from under 5% in early 2025. AI-themed startups now command over 50% of global venture capital funding. Inference spending has crossed 55% of all AI cloud infrastructure costs in early 2026, up from a third in 2023. These are not peripheral shifts. They represent a wholesale rewrite of the value chain that due diligence is meant to evaluate.

So what does the new audit actually look like?

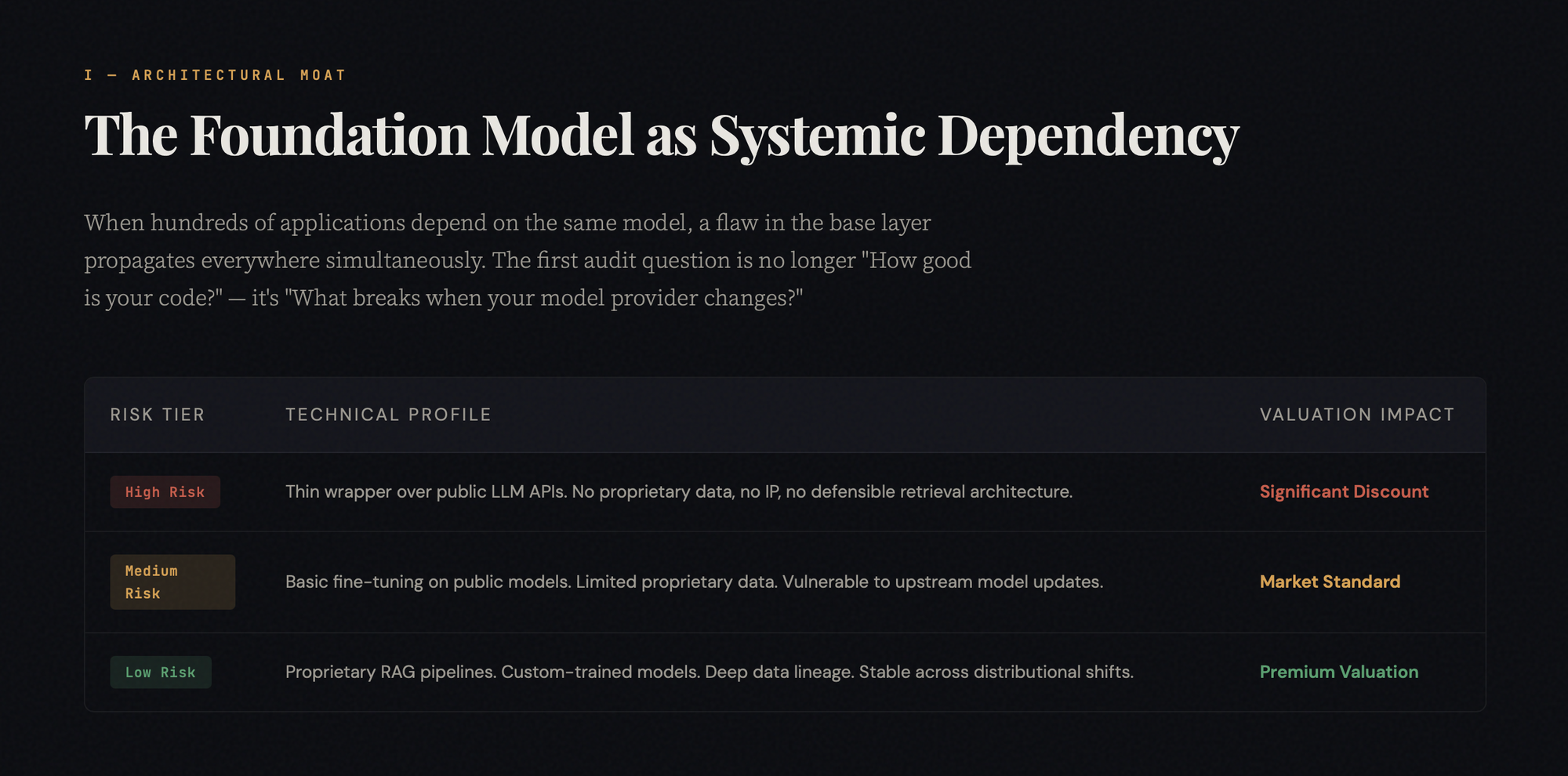

The Foundation Model as Systemic Dependency

The first structural break is homogenization. When hundreds of downstream applications are built on the same foundation model—whether GPT-4, Claude, Llama, or Gemini—a flaw in that base layer propagates across all of them at once. This is the monoculture problem from agriculture and the systemic risk problem from banking, now in software. A single bias in a foundation model is inherited by every derivative product. An API provider's pricing change can destroy a startup's unit economics overnight. A model deprecation can render an entire product line non-functional.

For the technical auditor, this means the opening question is no longer "How good is your code?" It is: "What is your dependency graph on foundation models, and what happens when that dependency breaks?"

The answer stratifies companies into three tiers. At the bottom are the thin wrappers—companies that have built an interface over a third-party API, with no proprietary data, no custom training, and no meaningful retrieval architecture. These face what the market quietly calls the "wrapper valuation discount." Their defensibility is a prompt template. Their moat is an API key.

In the middle are companies with moderate differentiation—basic fine-tuning on public models, a curated dataset, or some domain-specific retrieval. They are vulnerable to every upstream model update, but they have something of their own.

At the top are companies that have built proprietary RAG pipelines, custom-trained models on unique data, or developed novel architectures. Their performance is stable across distributional shifts. Their competitive position does not collapse when the provider ships a new version.

The due diligence question, stripped to its core: Where in the stack does proprietary value reside? And how resilient is that value to supply chain disruption in the model layer?

Agents and the Autonomy-Accountability Gap

The transition from generative AI to agentic AI—from text completion to task execution—represents the most consequential shift for risk assessment. An agent does not just suggest. It acts. It delegates tasks to tools, other agents, or humans. It makes decisions that the people overseeing it may not review, understand, or reverse.

The market is moving fast. 79% of organisations report some level of agentic AI adoption. 57% of companies surveyed by G2 already have agents in production. The agentic AI market is expanding at a 44% compound annual growth rate toward a projected $199 billion by 2034.

But the speed of adoption has outpaced the maturity of oversight. The fundamental question of diligence for any agentic system is not "Does it work?" It is: "What is the blast radius of an unsupervised decision?"

A customer service agent that autonomously issues a five-dollar refund has a small blast radius. A financial agent that rebalances a portfolio has an enormous one. The audit must map every autonomous action to its potential magnitude of consequence and verify that escalation thresholds are calibrated accordingly.

This is where the concept of "supervision burden" becomes critical. If an agent escalates to humans too often, it creates operational drag and defeats the purpose of autonomy. If it escalates too rarely, it risks catastrophic over-autonomy—decisions made at machine speed without human review, where a single error can dwarf years of efficiency gains.

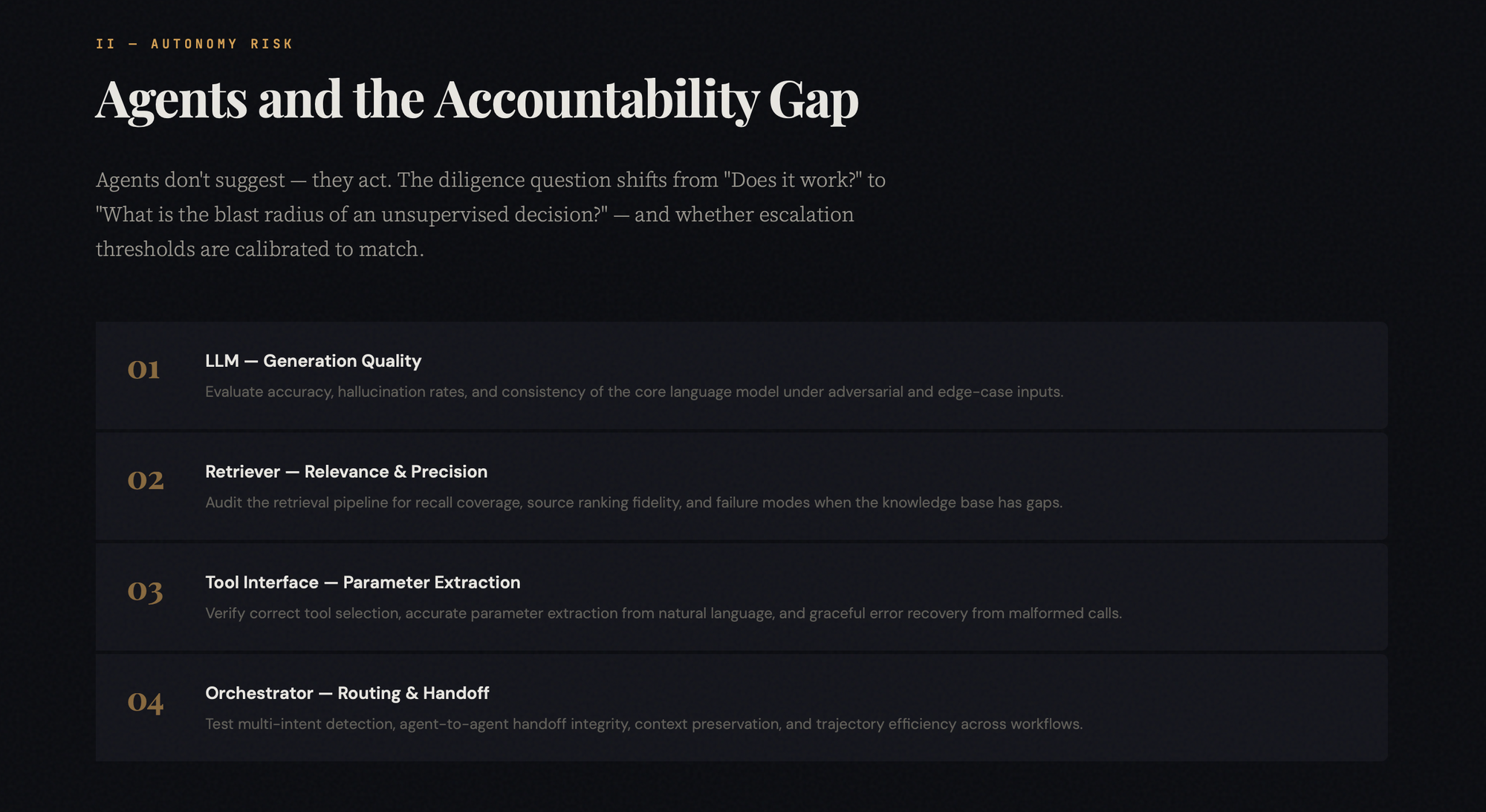

The audit must also decompose the system into its constituent parts: the LLM (generation quality), the retriever (relevance and precision), the tool interface (parameter extraction and error recovery), and the orchestrator (routing logic and handoff integrity). Agentic failures are almost always compositional. The model generates a correct plan, but the tool interface extracts the wrong parameters. The retriever surfaces relevant documents, but the orchestrator routes them to the wrong sub-agent. End-to-end testing, without decomposition, makes root cause analysis nearly impossible.

There is also a temporal dimension that compounds the difficulty. Agents drift faster than traditional software. A conventional SaaS product degrades over time due to technical debt. An agent can degrade suddenly—when the underlying model is updated, when user behaviour shifts, or when adversaries discover new interaction patterns. Due diligence cannot be a snapshot. It must evaluate the company's monitoring and retraining infrastructure, not just its current performance metrics.

Physical AI: When Software Failures Become Physical Harm

When intelligence is embedded in the material world—in robots, autonomous vehicles, surgical systems, or industrial machines—the failure mode changes fundamentally. A bad recommendation is an inconvenience. A bad actuator command is an injury, or worse.

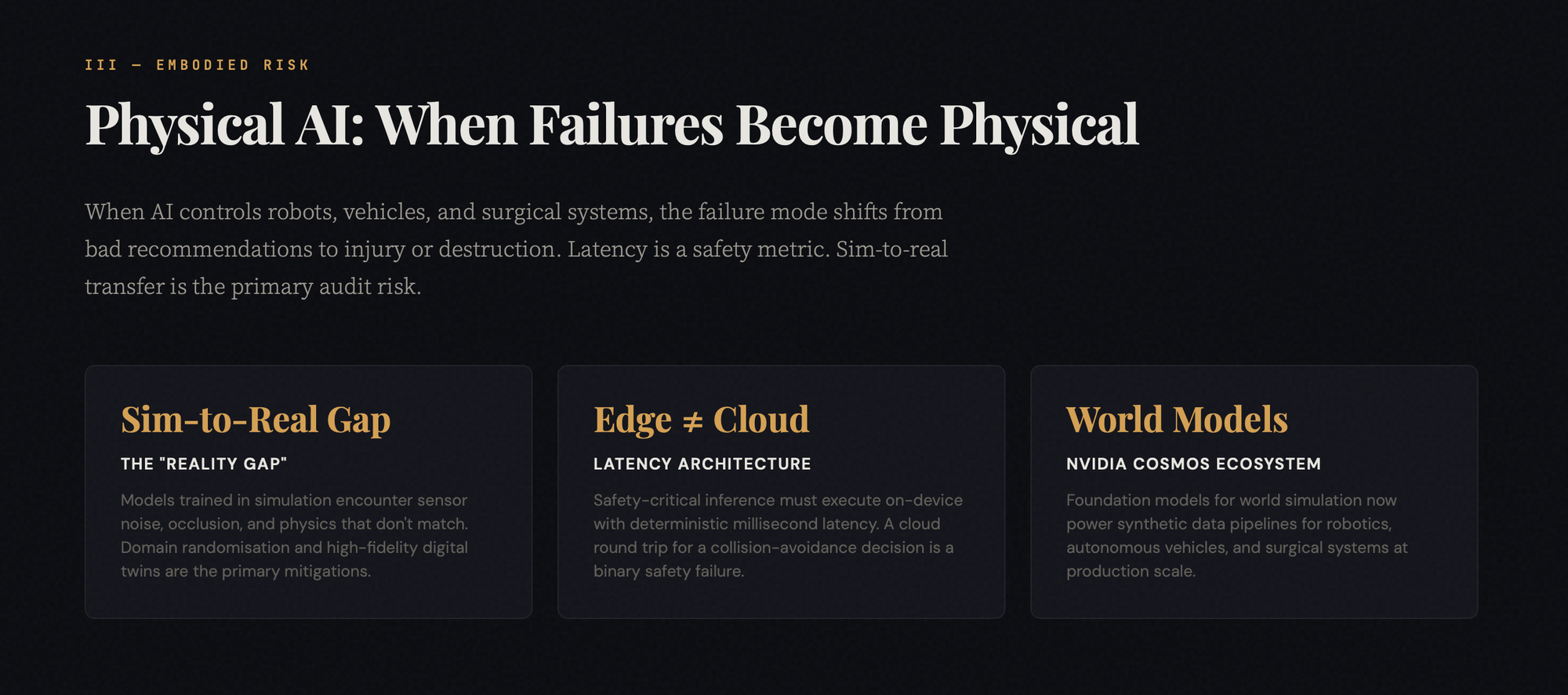

NVIDIA's Cosmos platform, its Isaac simulation frameworks, and its GR00T models for humanoid robots now represent an ecosystem where physical AI is moving from research into deployment. Companies like LEM Surgical are training autonomous surgical arms using Cosmos Transfer to generate synthetic data. Agility Robotics is scaling photorealistic training data through world foundation models. Caterpillar is building factory digital twins for simulation before physical deployment. This is no longer speculative.

The core audit challenge in physical AI is the "reality gap"—the distance between the simulated environment in which the model was trained and the physical world in which it must perform. Simulation offers perfect physics, clean sensor data, and predictable dynamics. The real world offers none of these. The due diligence must evaluate how a company manages domain randomisation, the fidelity of its digital twins, and, critically, its failure detection and recovery protocols when a sim-trained policy encounters something it has never seen.

Latency architecture is equally consequential. If a safety-critical inference, such as stopping a robotic arm before a collision, must traverse a network round-trip to a cloud server, the system is fundamentally unsafe, regardless of model quality. The audit must verify that all safety-critical decision loops execute locally on the device with deterministic latency bounds. This is a binary pass-fail criterion, not a performance optimisation.

The Inference Trap: When Success Becomes a Margin Crisis

The financial architecture of AI companies contains a trap that many investors have not yet fully internalised. Training cost—the massive GPU investment that produces the model—is a sunk cost: high, but finite and one-time. Inference cost—the compute consumed every time the model processes a request—is a variable cost that scales with every user, every API call, every agent action, indefinitely.

Inference now accounts for 80% to 90% of a model's total compute cost over its production lifecycle. The inference market is projected to grow from $106 billion in 2025 to $255 billion by 2030. Per-token costs have dropped 280-fold since early frontier models, yet total inference spending has grown 320%, because usage scales exponentially faster than costs decline.

The critical audit metric is gross margin under scale. Many AI products have attractive unit economics at low volume—the inference cost per user is manageable with a few thousand users. But as the user base grows, inference costs grow linearly, or worse, if the system uses complex chain-of-thought reasoning or multi-step agent workflows, while revenue may not grow proportionally.

The auditor must model the inference cost curve under realistic growth scenarios and verify the credibility of mitigation strategies, including model tiering (routing simple requests to smaller, cheaper models), quantisation, caching, and distillation. GPU utilisation is the overlooked indicator. With industry averages of 40% to 60%, many companies pay for nearly twice as much compute as they actually use. Improving utilisation to 70–80% through better scheduling delivers the equivalent return of a 30% price reduction. Its absence signals operational immaturity.

The Semantic Attack Surface

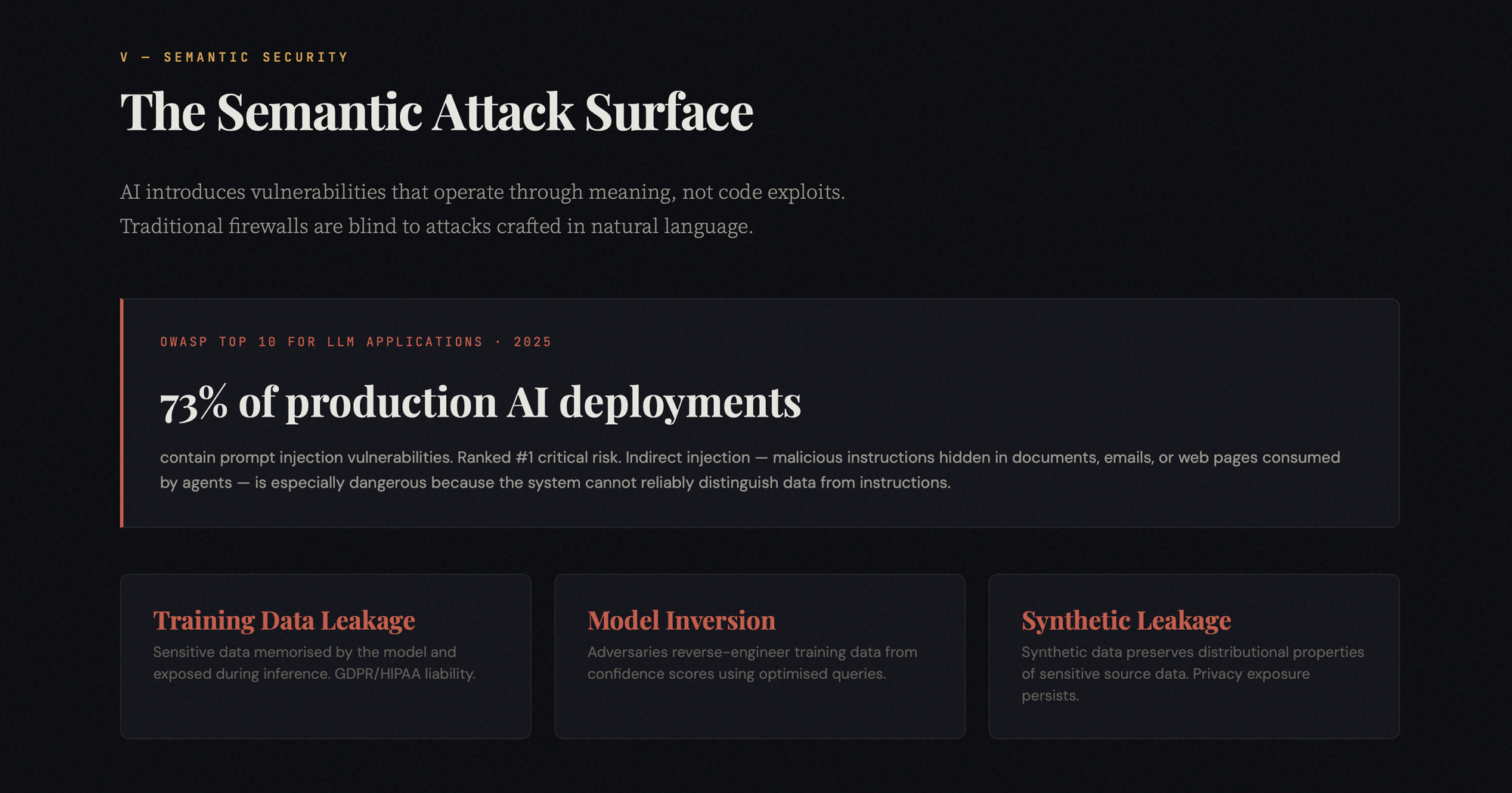

Traditional security audits test firewalls, authentication, and encryption. AI introduces an entirely new class of vulnerability that operates at the semantic layer — through the meaning of inputs, not through technical exploits.

Prompt injection ranks number one on OWASP's 2025 Top 10 for LLM Applications, appearing in over 73% of production deployments assessed during security audits. But the more insidious variant is indirect injection: malicious instructions embedded in documents, web pages, or emails that the agent consumes as data. When the agent summarises that content, it unknowingly executes the hidden commands. The system cannot reliably distinguish between data to be processed and instructions to be followed, because both arrive as natural language.

Model inversion attacks compound the risk—adversaries systematically query the model and analyse confidence distributions to reconstruct training data or proprietary information. Defences include differential privacy, output masking, and rate limiting, but the auditor must verify that at least some combination of these is implemented and tested, not just planned.

Data provenance adds a further liability surface. Recent litigation over the use of pirated books in model training has demonstrated that the legal exposure is real and potentially measured in the billions. Many companies genuinely do not know the full provenance of their training data. The lineage was never tracked with the rigour required for a legal challenge. And the synthetic data defence — the argument that using AI-generated training data eliminates privacy concerns — has been empirically undermined by research showing that synthetic outputs can still leak information about real individuals through structural overlap in the data manifold.

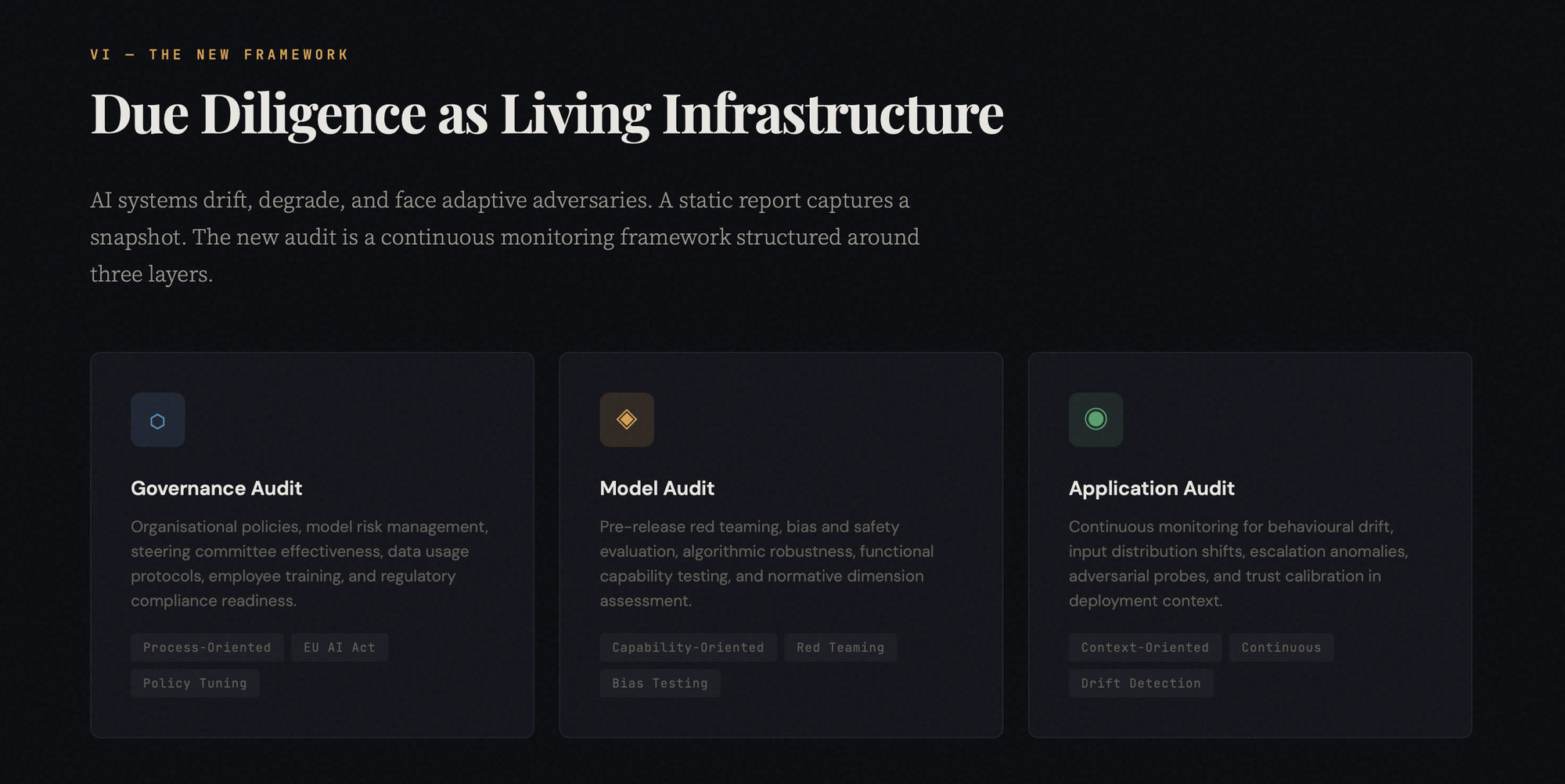

Due Diligence as Living Infrastructure

The deepest structural implication is that technical due diligence can no longer be a point-in-time report. AI systems are living systems. They drift, degrade, encounter novel distributions, and interact with adversaries that constantly adapt. A diligence report that captures the system's state in January may be materially misleading by March.

The output of due diligence must shift from a static document to a continuous monitoring framework, structured around three layers. First, governance audits: organisational policies, model risk management, steering committees, data usage protocols. Second, model audits: pre-release red teaming, bias evaluation, safety testing, and algorithmic robustness. Third, application audits: continuous monitoring for behavioural drift, shifts in input distribution, anomalies in escalation rate, and adversarial probe frequency.

Each layer must be instrumented for ongoing observation, not one-time evaluation. Compliance with the EU AI Act and emerging global frameworks is now binary: pass or fail. Explainability is a market-access requirement in healthcare and financial services, not a nice-to-have. The economic discipline of AI FinOps—tracking cost-per-prediction, cost-per-automated-decision, inference spend as a percentage of revenue—must be embedded into the audit as rigorously as traditional financial analysis.

The old playbook—reviewing code repositories, interviewing the CTO, stress-testing the API—is necessary but insufficient. The new audit must reach into the system's probabilistic core, the economics of inference at scale, the legal exposure of data provenance, the physical safety implications of embodied deployment, and the adversarial resilience of the semantic layer.

The companies that will command premium valuations in this era are not necessarily those with the most sophisticated models. They are those whose technical architecture, economic structure, and governance infrastructure can withstand the scrutiny of a due diligence process that has finally caught up with the complexity of what it is being asked to evaluate. The future of due diligence is not a report that sits on a shelf. It is a continuous loop of monitoring, retraining, and policy adaptation that evolves as rapidly as the systems it seeks to govern.

The audit, as we knew it, is possibly over. What replaces it will determine who builds lasting value — and who merely rides the wave until it breaks.