Recognizing the loss of sovereignty to vendors is challenging. Addressing this issue is even more complex.

Most enterprises, when they realize their operational dependence on vendor logic, perceive a false choice: either remove existing integrations at significant cost or accept ongoing dependency. Both options are unsustainable. The first jeopardizes business continuity, while the second relinquishes strategic control.

However, this perspective is incomplete. A third option is to reconsider how systems are architected when vendors are part of the solution.

The future does not belong to enterprises that avoid external AI platforms. It belongs to those who use them without ceding control over the logic that defines competitive differentiation, ethical boundaries, and strategic intent. This requires a fundamental shift in how enterprise architecture is conceived, from integration-first thinking to sovereignty-first design.

The key question is not whether logic should be owned, but which logic must be owned and how to architect systems that balance ownership and delegation without fragmentation.

Why Most Architectures Fail the Sovereignty Test

Historically, enterprise architecture has prioritized interoperability over control. Systems are built to connect, integrate, and exchange data, assuming that reliable data flow and APIs ensure sound architecture.

That model collapses when execution shifts from humans interpreting data to software acting autonomously.

In traditional architectures, a vendor platform might provide analytics, and humans decide what to do with the insights. Sovereignty is preserved because the final decision, the moment intent becomes action, remains human. But when the vendor platform not only recommends but also executes, the architecture transfers authority without explicitly designing for that transfer.

The failure is not technical. It is conceptual. The architecture was never asked to preserve sovereignty because it was assumed to reside in humans, not systems. Once systems begin acting autonomously, that assumption breaks.

What is needed is not better integration, it is explicit architectural separation between logic the enterprise must own and logic it can safely delegate. Most enterprises have never drawn that line.

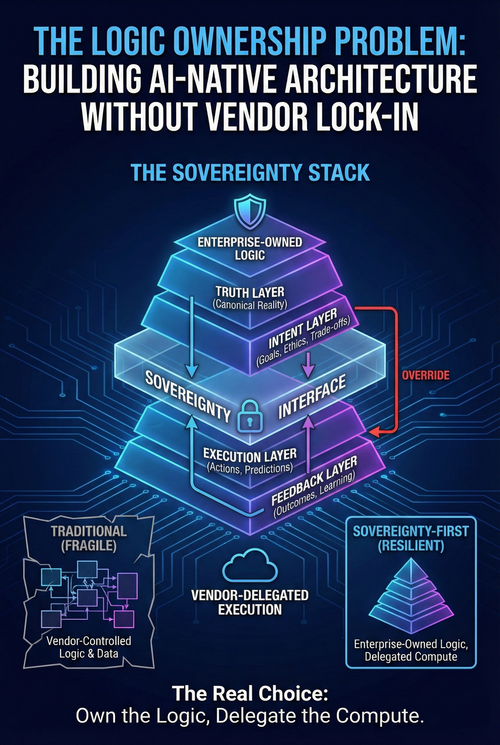

The Sovereignty Stack: Layering Control

Sovereignty-preserving architecture operates on a layered model where each layer has explicit ownership and interface contracts. This is not a new concept; layered architectures have existed for decades, but the criteria for each layer must shift when AI is involved.

At the foundation sits the truth layer. Here, the enterprise defines what is real: customer identity, product catalog, financial state, and operational constraints. This layer must be internally controlled. If the enterprise does not own the canonical definition of its reality, it has already ceded sovereignty. Vendors can synchronize with this layer, but they cannot define it.

Above is the intent layer, where the enterprise encodes optimization goals, acceptable trade-offs, and unacceptable outcomes, including risk tolerances, ethical boundaries, and strategic priorities. Intent must be machine-interpretable to govern automated execution. This layer must also be owned; if a vendor defines what is good, the enterprise follows an external strategy.

The execution layer is where decisions are made and actions are taken. Vendors can operate here, but only under constraints defined by the intent layer. Vendors provide capabilities such as optimization algorithms, predictive models, and recommendation engines, but the enterprise retains the right to override, inspect within agreed boundaries, and define success criteria.

Finally, the feedback layer captures outcomes and feeds them back into the intent layer. Here, the enterprise learns whether its encoded logic aligns with reality. If this layer is controlled by the vendor, the enterprise cannot adapt independently.

The critical insight is that vendors can participate in execution and provide feedback analysis, but they must not own the truth or intent. When those layers are vendor-controlled, sovereignty has been structurally transferred.

Sovereignty Interfaces: The Abstraction That Preserves Control

The technical mechanism for preserving sovereignty while leveraging vendor capabilities is the sovereignty interface, an abstraction layer between enterprise-owned logic and vendor-provided execution.

A sovereignty interface differs from a traditional API. It serves as a contract enforcing three principles: inspectability, overridability, and portability.

Inspectability means the enterprise can audit how decisions are made. If a vendor model recommends an action, the interface must surface the logic behind that recommendation, not necessarily the model weights, but the reasoning pathway, confidence levels, and which rules were applied. Opacity is not acceptable. If the enterprise cannot understand why a decision was made, it cannot govern the system.

Overridability means the enterprise retains the technical and contractual right to countermand vendor logic in real time. This is not the same as configuration. Configuration adjusts parameters within a vendor's framework. Override changes the decision itself, substituting enterprise judgment for vendor output. If the override requires vendor approval or adds significant friction, sovereignty is compromised.

Portability means the enterprise can switch vendors, migrate to internal capabilities, or run multiple providers in parallel without prohibitive switching costs. This is enforced through standardized interfaces that encapsulate vendor-specific logic, enabling replacement without rewriting enterprise systems. If changing vendors requires rearchitecting core workflows, the enterprise is locked in.

Sovereignty interfaces are not about eliminating vendor value. They ensure vendor capabilities operate as governed services rather than black-box authorities. The vendor provides intelligence; the enterprise provides judgment.

The Build-vs-Buy Decision Reframed

Traditional build-vs-buy frameworks optimize for cost, speed, and capability gaps. The question is: can we build this faster and cheaper than buying it, or does the vendor have expertise we lack?

In a sovereignty-preserving model, the focus shifts to whether the logic defines competitive differentiation, ethical commitments, or existential risk. If so, it must be owned, regardless of cost or speed. Otherwise, it can be delegated to vendors with appropriate sovereignty interfaces.

This reframing changes procurement priorities. A pricing algorithm that defines competitive positioning should not be vendor-controlled, even if the vendor's model is technically superior. A fraud detection system that enforces acceptable risk thresholds must allow enterprise override, even if that introduces latency. A recommendation engine that shapes customer experience must be inspectable, even if that requires custom integration work.

Conversely, capabilities that are truly commoditized—email routing, basic analytics, infrastructure management—can be fully delegated because they do not encode strategic intent. The enterprise does not need sovereignty over how email is delivered. It needs sovereignty over which emails are prioritized and why.

The error most enterprises make is treating all software as equivalent and optimizing for efficiency universally. This leads to situations where strategically critical logic is vendor-controlled simply because the vendor's solution was faster to deploy.

Sovereignty-first architecture inverts this. It starts by identifying which decisions must remain under enterprise control, and only then asks how to deliver those capabilities, whether through internal build, vendor partnership with sovereignty interfaces, or hybrid models.

Hybrid Sovereignty: Own the Logic, Delegate the Compute

A highly effective sovereignty-preserving approach is a hybrid architecture in which the enterprise owns the decision logic but delegates execution infrastructure.

In this model, the enterprise encodes its intent, constraints, and optimization goals internally. These become the governing rules. Vendor platforms provide computational power, pre-trained models, and domain expertise, but operate as execution engines rather than decision authorities.

For example, an enterprise might define its own customer lifetime value model, risk-scoring methodology, or resource-allocation logic. That logic is encoded in enterprise-controlled systems. When execution is required, the enterprise calls vendor APIs for predictions, computations, or optimizations, but the final decision is made by enterprise logic, not vendor recommendations.

This preserves sovereignty because the enterprise retains control over what is optimized for and how trade-offs are resolved. The vendor provides intelligence such as data patterns, predictive signals, and efficiency algorithms, but the enterprise decides how that intelligence is used.

Importantly, this model enables the enterprise to change vendors without altering decision logic. For instance, adopting a new fraud detection API does not affect risk thresholds or override policies. Logic remains portable while execution is delegated.

This is not costless. It requires the enterprise to invest in its own logic layer, maintain semantic definitions, and develop expertise in translating strategic intent into enforceable rules. But the alternative, complete dependence on vendor logic, is strategically untenable.

Contractual Sovereignty: Negotiating Decision Rights

Technical architecture alone cannot preserve sovereignty if contracts do not support it. Most vendor agreements grant the vendor unilateral control over model updates, logic changes, and platform evolution. The enterprise has no recourse when changes conflict with strategy.

Sovereignty-preserving contracts must explicitly govern decision rights, not just data rights.

First, the contract must grant the enterprise audit rights. This means the vendor agrees to provide transparency into how decisions are made—not trade secrets or proprietary model details, but reasoning paths, confidence intervals, and which rules are applied. If the vendor refuses, the enterprise should treat that as a sovereignty risk and evaluate alternatives.

Second, the contract must define override authority. The enterprise must have the technical and legal right to override vendor recommendations in real time without penalty. If override triggers breach-of-warranty clauses or voids support agreements, sovereignty is illusory.

Third, the contract must address portability. Exit clauses should include provisions for data export in usable formats, API compatibility during transition periods, and limits on switching costs. If the vendor can make migration prohibitively expensive, the enterprise has no leverage.

Fourth, the contract must govern update cycles. The vendor should not be able to force changes to the logic that conflict with the enterprise strategy. The enterprise must have the right to defer updates, test them in isolation, or opt out if they degrade performance against enterprise-defined success criteria.

Fifth, the contract should include provisions for multi-sourcing. The enterprise should be allowed to run competing vendor solutions in parallel, compare outputs, and choose between them dynamically. If the contract requires exclusivity, sovereignty is compromised from the start.

These clauses are rarely included in standard SaaS agreements because most enterprises do not request them. Procurement teams focus on cost, SLAs, and data privacy. They rarely negotiate for decision sovereignty because the concept is not well understood.

This must change. As AI systems move from advisory to autonomous, decision rights become as strategically important as data rights. Contracts that do not address them are structurally insufficient.

The Economics of Sovereignty-Preserving Architecture

Building and maintaining sovereignty-preserving architecture is more costly than relying solely on vendors. It requires investment in internal logic layers, semantic infrastructure, and governance, which increases complexity and slows initial deployment.

However, these costs must be weighed against the risk of strategic lock-in.

When an enterprise cedes control over decision logic, it loses the ability to differentiate. If every competitor uses the same vendor platform with the same embedded logic, competitive advantage collapses to execution efficiency within vendor-defined constraints. Markets commoditize.

In contrast, enterprises that retain sovereignty over critical logic can differentiate on dimensions that vendors do not address. They can optimize for long-term customer value when vendors optimize for short-term conversion. They can enforce ethical constraints that vendors do not encode. They can serve niche markets that vendor platforms, trained on mass-market data, systematically underserve.

The economic value of this differentiation often exceeds the cost of maintaining sovereign architecture. But that value is difficult to quantify upfront, which is why CFOs and procurement teams default to vendor dependency. The savings are immediate and measurable. The strategic cost compounds slowly and becomes visible only when changing course is no longer feasible.

Leadership must reframe the evaluation. The question is not "how much does sovereignty cost?" but "what is the cost of losing it?" In most cases, that cost, measured in strategic rigidity, competitive commoditization, and loss of agency, far exceeds the investment required to preserve control.

Designing for Partial Sovereignty

Not all decisions require the same level of control. Sovereignty-preserving architecture does not mean owning everything. It means being explicit about what must be owned and architecting boundaries that allow delegation without fragmentation.

High-sovereignty domains, those involving competitive differentiation, ethical commitments, or existential risk, require full ownership of truth, intent, and execution logic. Vendors can provide computational support, but the enterprise must retain override authority and portability.

Medium-sovereignty domains, those involving operational efficiency or tactical optimization, can use vendor logic with sovereignty interfaces. The vendor provides the default behavior, but the enterprise retains the right to inspect, override, and migrate.

Low-sovereignty domains, those involving commoditized capabilities with minimal strategic impact, can be fully delegated to vendor platforms. The enterprise accepts vendor logic, updates, and constraints because the risk of misalignment is low and the cost of ownership is unjustified.

The architectural challenge is ensuring these domains remain isolated. A low-sovereignty vendor platform should not influence high-sovereignty decisions. If a commoditized analytics tool begins shaping strategic resource allocation, sovereignty has leaked across boundaries.

This requires explicit interface contracts, strict separation of truth layers, and governance processes that monitor where vendor logic influences enterprise decisions. Partial sovereignty is sustainable only if boundaries are maintained.

The Organizational Shift Required

Sovereignty-preserving architecture is not purely technical. It requires organizational change.

Most enterprises today have fragmented ownership of AI capabilities. Data teams build models, IT manages infrastructure, business units procure vendor platforms, and legal negotiates contracts. No single function owns the question of sovereignty.

This fragmentation is itself a sovereignty risk. When no one is responsible for ensuring decision rights are preserved, those rights are lost by default.

What is needed is a function, whether a role, a team, or a governance body, that owns logic sovereignty. This function is responsible for:

Identifying which decisions must remain enterprise-controlled based on strategic importance, not technical feasibility. Defining sovereignty interfaces and ensuring they are enforced in vendor contracts and system architecture. Auditing where external logic influences internal decisions and flags concentration risks. Negotiating for decision rights in vendor agreements and pushing back when vendors resist transparency or portability. Maintaining the enterprise's truth and intent layers and ensuring they remain independent of vendor platforms.

This is not a purely technical or purely legal role. It sits at the intersection of strategy, architecture, and governance. It requires understanding both what the enterprise optimizes for and how that intent is translated into executable logic.

Most enterprises do not have this function today. They will need it. As AI systems move from tools to agents, the question of who owns decision logic becomes existential.

What Success Looks Like

An enterprise operating under a sovereignty-preserving architecture does not avoid vendors. It uses them strategically.

Vendors provide computational efficiency, domain expertise, and continuous innovation. But they operate as governed services, not autonomous authorities. The enterprise retains the ability to monitor how decisions are made, override vendor logic when it conflicts with strategy, and migrate to alternatives without incurring prohibitive costs.

Contracts explicitly grant decision rights, not just data rights. Updates cannot be forced. Override is a design feature, not an exception. Portability is contractually guaranteed.

Internally, the enterprise maintains its own truth and intent layers. It knows what it optimizes for, what trade-offs are acceptable, and which outcomes are prohibited. That logic is machine-interpretable and governs execution, whether internally or through vendor APIs.

When strategy shifts, the enterprise can propagate changes across all systems, vendor and internal, almost instantly. It is not waiting for vendor roadmaps or negotiating custom features. It owns the logic and controls the pace of evolution.

This is not utopian. It is architecturally achievable. But it requires deliberate design, contractual discipline, and organizational commitment. Most enterprises will not get there by accident. They must design for sovereignty from the start.

The Real Choice

The sovereignty trap is not inevitable. It results from accumulated architectural decisions made without considering control.

Enterprises that retain agency in the age of AI will not be those that build everything internally. They will be those who deliberately architect dependencies, explicitly negotiate for decision rights, and measure sovereignty as rigorously as they measure cost.

The question is not whether to use vendor AI. It is whether the enterprise knows which logic it must own, how to preserve that ownership even when execution is delegated, and what contractual and technical mechanisms enforce that separation.

In the era of autonomous systems, data ownership is necessary but not sufficient. Logic ownership is essential. Enterprises that control decision-making will define markets; those who delegate control will be defined by others.

Sovereignty is not about avoiding vendors, but about leveraging them without surrendering the logic that ensures strategic distinction.

This is the architecture required for the next decade.