Most enterprises believe AI threatens their sovereignty. In reality, their vendors do.

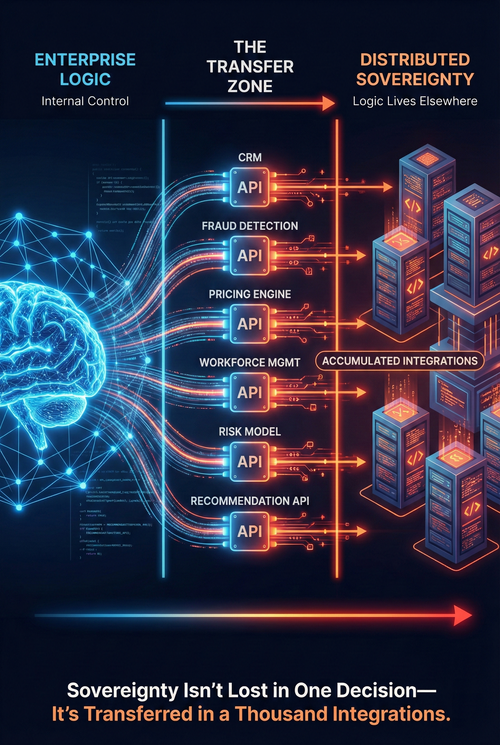

This is not a story about rogue algorithms or runaway automation. It is a story about accumulated architectural decisions that seem efficient in isolation but collectively transfer control. Every API call to a vendor's recommendation engine, every integration with a SaaS platform that "optimizes" workflows, every adoption of a pre-trained model whose logic cannot be inspected—these are not merely technical choices. They are sovereignty transfers.

Many organizations only realize their lack of control when changing course becomes prohibitively costly.

Where Decision Logic Actually Lives

Ask most enterprises where their decision logic resides, and they will point to their systems, their data, and their people. But in reality, an increasing share of operational decisions—what to prioritize, which customers to target, how to route resources, when to escalate risk—are governed by logic that lives elsewhere.

When a sales team uses a CRM that scores leads and suggests next actions, who decides the weighting? When a support platform auto-prioritizes tickets, whose assumptions about urgency are embedded? When a fraud detection API flags transactions, can the enterprise inspect the threshold logic or only observe outcomes?

Usually, it's the vendor's logic running the show. The enterprise relies on designs it cannot audit, override, or inspect.

This is not an accident. It is the natural outcome of how modern enterprise software is built and sold.

The Economics of Vendor Logic

Vendors optimize for a fundamentally different objective than their customers. An enterprise needs control over how decisions are made in its specific context. A vendor needs to build once and sell to thousands.

That structural tension creates a predictable pattern. Vendors encode best practices into their platforms—decision rules, prioritization logic, optimization algorithms—that reflect aggregated learning across their customer base. For the vendor, this is efficient. For the enterprise, it is a transfer of sovereignty to a shared, multi-tenant logic layer.

Consider what happens when a workforce management platform recommends shift schedules, a pricing engine suggests discounts, or a demand forecasting tool predicts inventory needs. These systems are not executing the enterprise's intent. They are executing the vendor's interpretation of what intent should look like, shaped by data from hundreds or thousands of other customers.

In single-tenant environments, this might be negotiable. In multi-tenant SaaS—the dominant model—it is architectural. The logic is shared because the infrastructure is shared. Your competitor's behavior influences the model your system uses. Updates to the platform's decision rules propagate to all customers simultaneously, whether those changes align with your strategy or not.

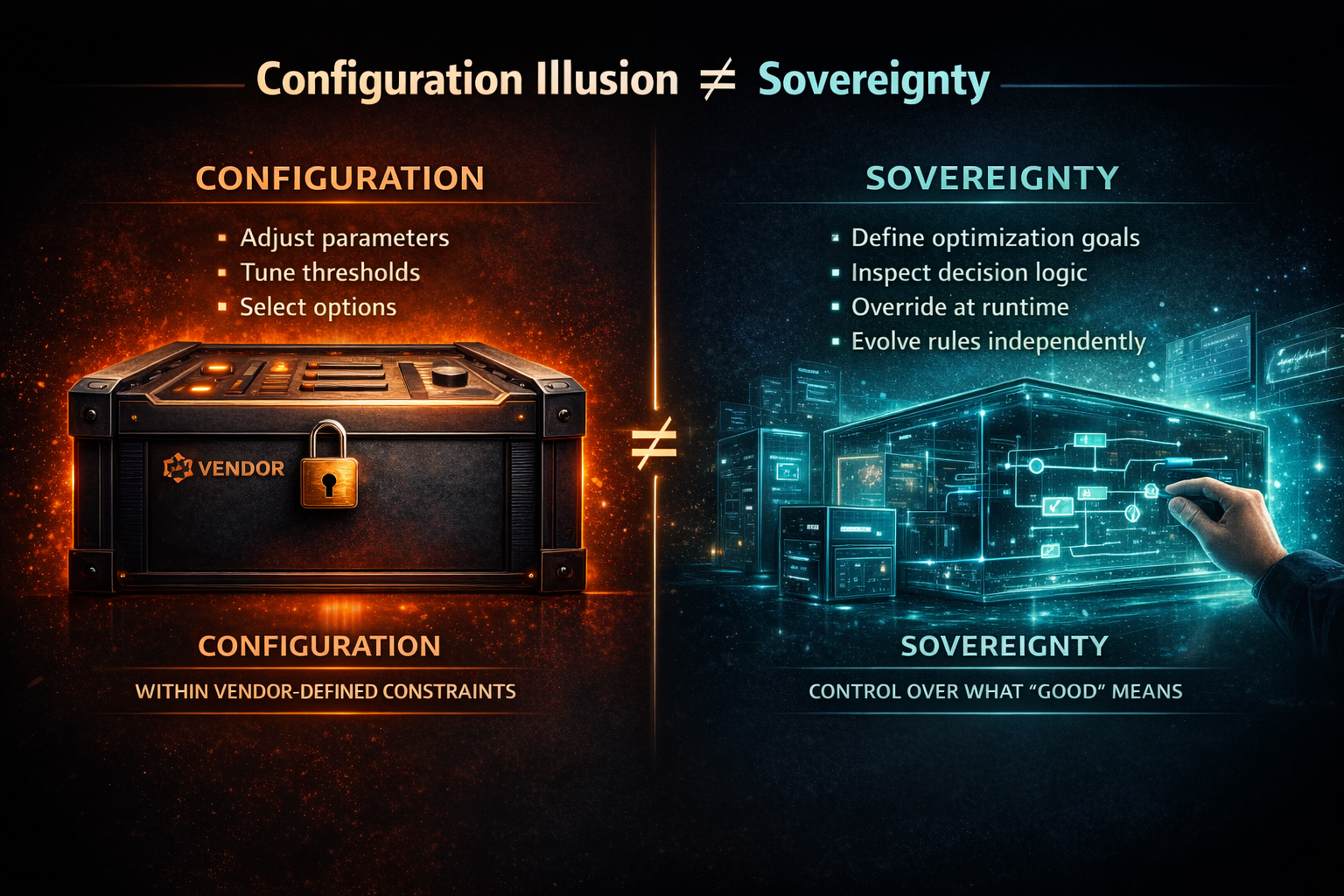

The Illusion of Configuration

Vendors know enterprises want control, so they offer configuration. Adjust these sliders. Choose from these options. Set your thresholds here.

But configuration is not sovereignty; it is merely the freedom to operate within constraints set by others.

True sovereignty means the ability to define what is optimized for, not just adjust how aggressively it is pursued. It means control over the logic that determines what good looks like, not just the parameters that tune execution. And it means the right to override, inspect, and evolve decision rules when reality shifts.

Most vendor platforms do not offer this. They offer configurability within a fixed model of how decisions should work. The enterprise can adjust, but it cannot redefine. It can tune, but it cannot redesign.

This matters most when the vendor's embedded assumptions diverge from the enterprise's reality. A retail platform optimized for high-volume, low-margin commerce does not transfer well to luxury goods. A hiring platform trained on tech industry norms imposes those norms on healthcare or manufacturing. A financial risk model built for stable markets fails catastrophically during volatility.

In each case, the enterprise is constrained by logic it did not choose and often cannot see.

When Recommendations Become Constraints

The most insidious erosion of sovereignty happens when vendor outputs are treated as authoritative rather than advisory.

A recommendation engine suggests a course of action. The human operator, lacking context on how that recommendation was generated, defers to it. Over time, deference becomes routine. The system's output is no longer questioned—it is followed. At that point, the recommendation has become a de facto constraint, even if no formal authority was ever granted.

This is not a failure of the technology. It is a failure of organizational design. When humans do not understand the logic behind a recommendation, cannot override it without significant friction, and are measured on outcomes the system optimizes for, they stop exercising judgment. The vendor's embedded logic becomes the enterprise's operating reality.

Enterprises don't decide to give up control. They drift into dependence.

The Contractual Blindness

Most vendor contracts govern data rights, uptime guarantees, and pricing. Almost none govern decision rights.

Enterprises negotiate for ownership of their data, but not for ownership of the logic that acts on it. They demand SLAs for system availability, but not for the ability to inspect or override decision algorithms. They scrutinize cost structures, but rarely ask: what happens when we need to change how this system decides?

This is not because legal teams are negligent. It is because the question is not being asked at the right level. Procurement treats AI platforms as software purchases, not as sovereignty transfers. The conversation focuses on features, integrations, and user seats—not on who controls the logic that will govern thousands of daily decisions.

By the time the enterprise realizes it needs to change course—market conditions shift, strategy pivots, regulatory requirements tighten—it discovers that the vendor controls the update cycle, the model training process, and the threshold logic. The enterprise can request changes, but it cannot compel them. It can switch vendors, but only at a prohibitive cost.

Sovereignty was transferred in the contract, but the contract did not name it.

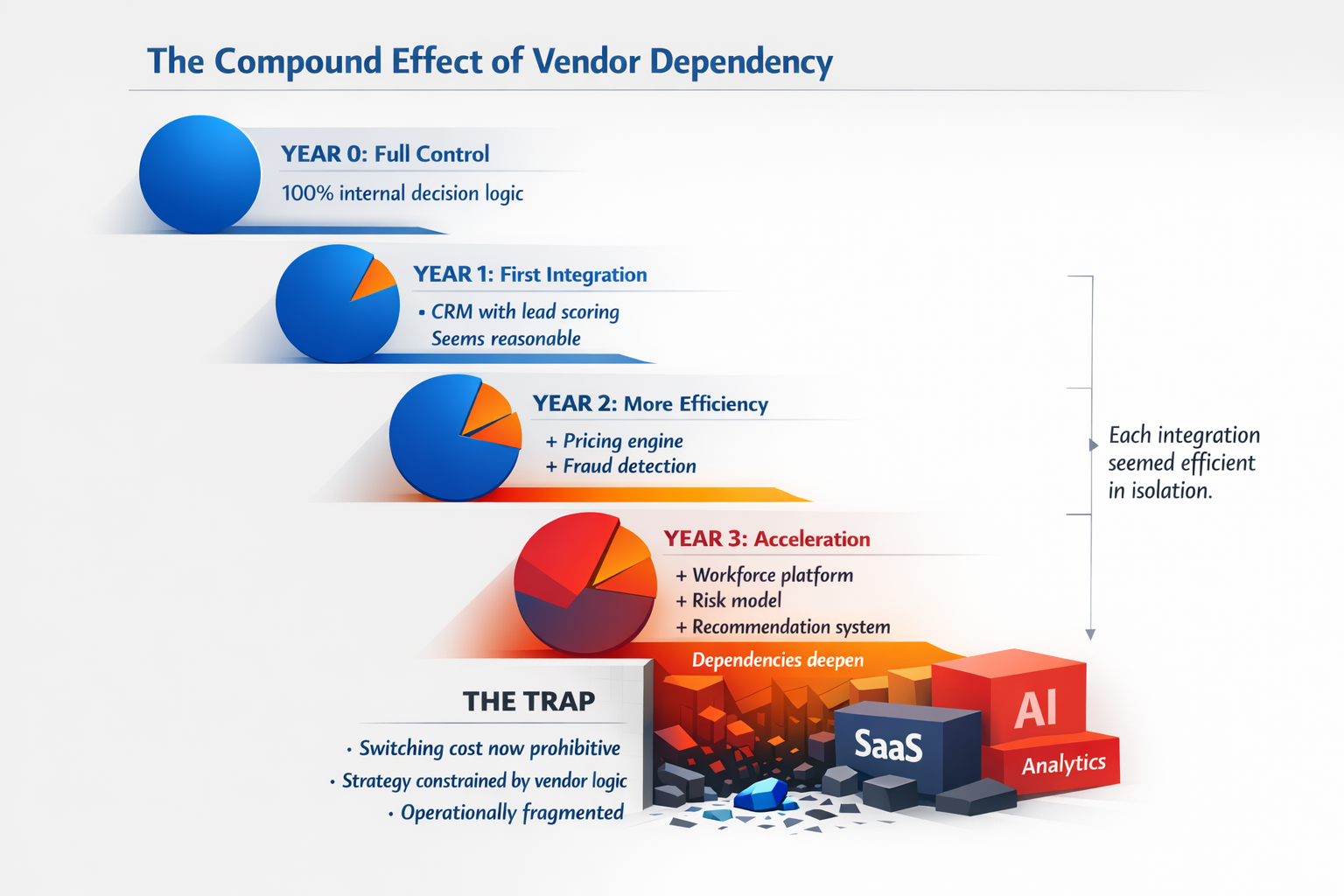

The Compound Effect of Integration

No single integration transfers complete sovereignty. Each one seems reasonable in isolation. A pricing tool here, a routing engine there, a risk model integrated with operations. Each decision is defensible: faster time-to-value, lower upfront cost, access to vendor R&D.

Sovereignty fades not in a single moment, but by steady accumulation.

After dozens of integrations, the enterprise's decision fabric is no longer its own. The logic that determines which leads to pursue, which risks to escalate, how to allocate resources, and when to intervene is distributed across vendor platforms, each optimizing for objectives the enterprise did not define and cannot change.

At this point, the enterprise's strategy is constrained not by its own judgment, but by the sum of its vendors' embedded assumptions. It can no longer act as a unified entity with coherent intent. It has become a collection of vendor logics, loosely coordinated by humans who lack the authority to override any of them.

The organization is sovereign in name but operationally fragmented.

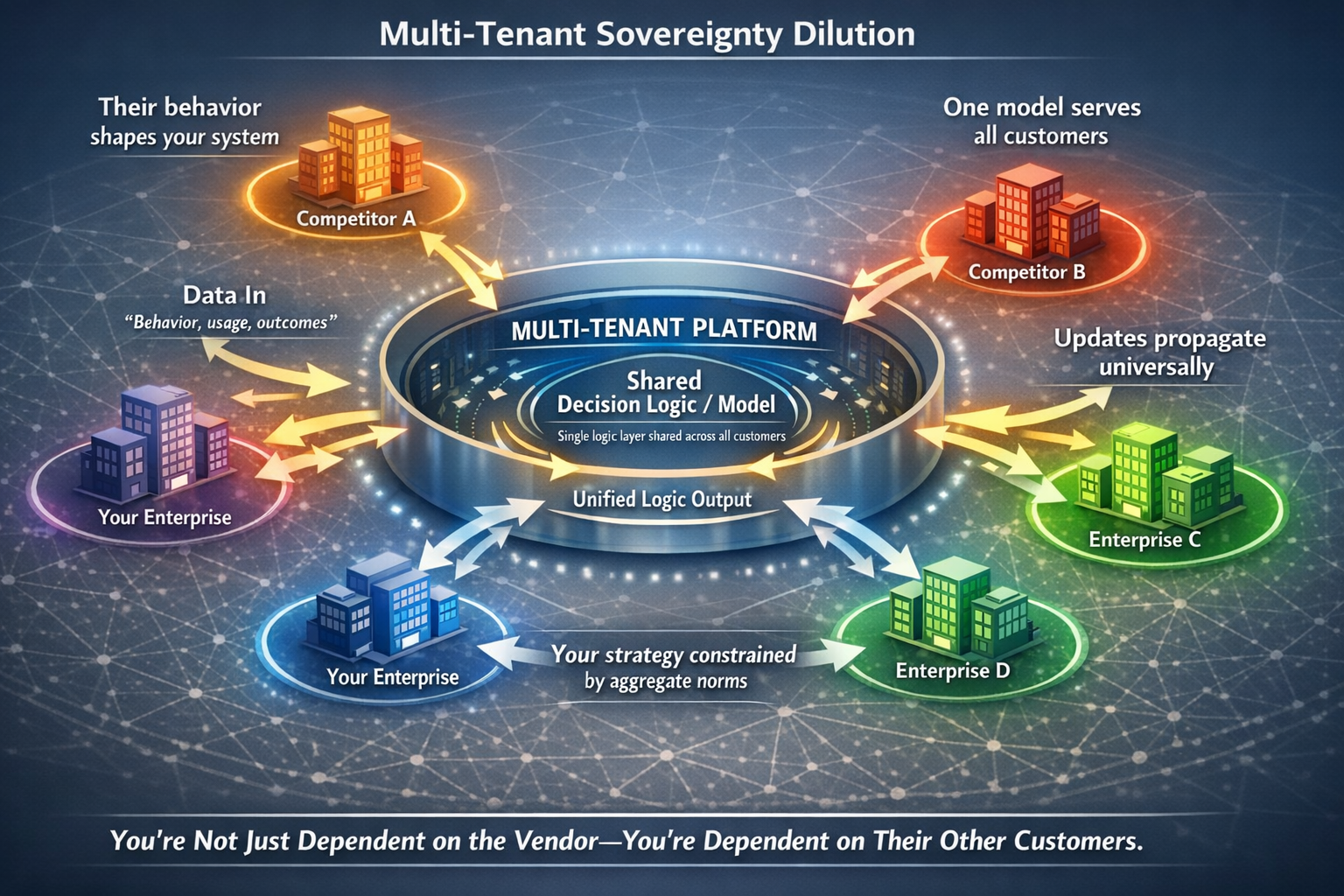

What Multi-Tenant Architecture Actually Means

Multi-tenant SaaS is sold as efficiency: shared infrastructure, continuous updates, economies of scale. What is rarely discussed is the sovereignty implication.

In a multi-tenant model, the platform serves thousands of customers using the same underlying logic. When the vendor updates its recommendation algorithm, fraud-detection model, or optimization heuristic, the change propagates to all customers. There is no customer-specific logic. There is only the platform logic, with limited configurability at the margins.

This has a subtle but profound consequence: your competitors' behavior shapes your system's performance.

If the vendor's model is trained on aggregated data from all customers, then what works well for high-performing customers becomes the norm the system optimizes for. If your strategy diverges from that norm—if you compete on different dimensions, serve different segments, or operate in different conditions—the platform's logic may systematically misalign with your objectives.

You are now dependent on both the vendor and their other customers.

This is why enterprises in regulated industries, niche markets, or unconventional strategies struggle with off-the-shelf platforms. The logic baked into those platforms reflects the mass market, not the edge cases. Sovereignty requires the ability to define edge cases as strategic differentiation, not as errors to be corrected.

The Sovereignty Audit

If sovereignty is being lost through tooling, it can be reclaimed through architecture. But reclamation requires visibility.

Enterprises need to know where external logic governs internal decisions. This is not a compliance exercise. It is a strategic audit of where control actually resides.

The audit begins with a simple question: for every decision the enterprise makes at scale, where does the governing logic live?

First, map decision points. Not just major strategic decisions, but operational ones: pricing, prioritization, resource allocation, escalation, approval. These are the moments where intent becomes action.

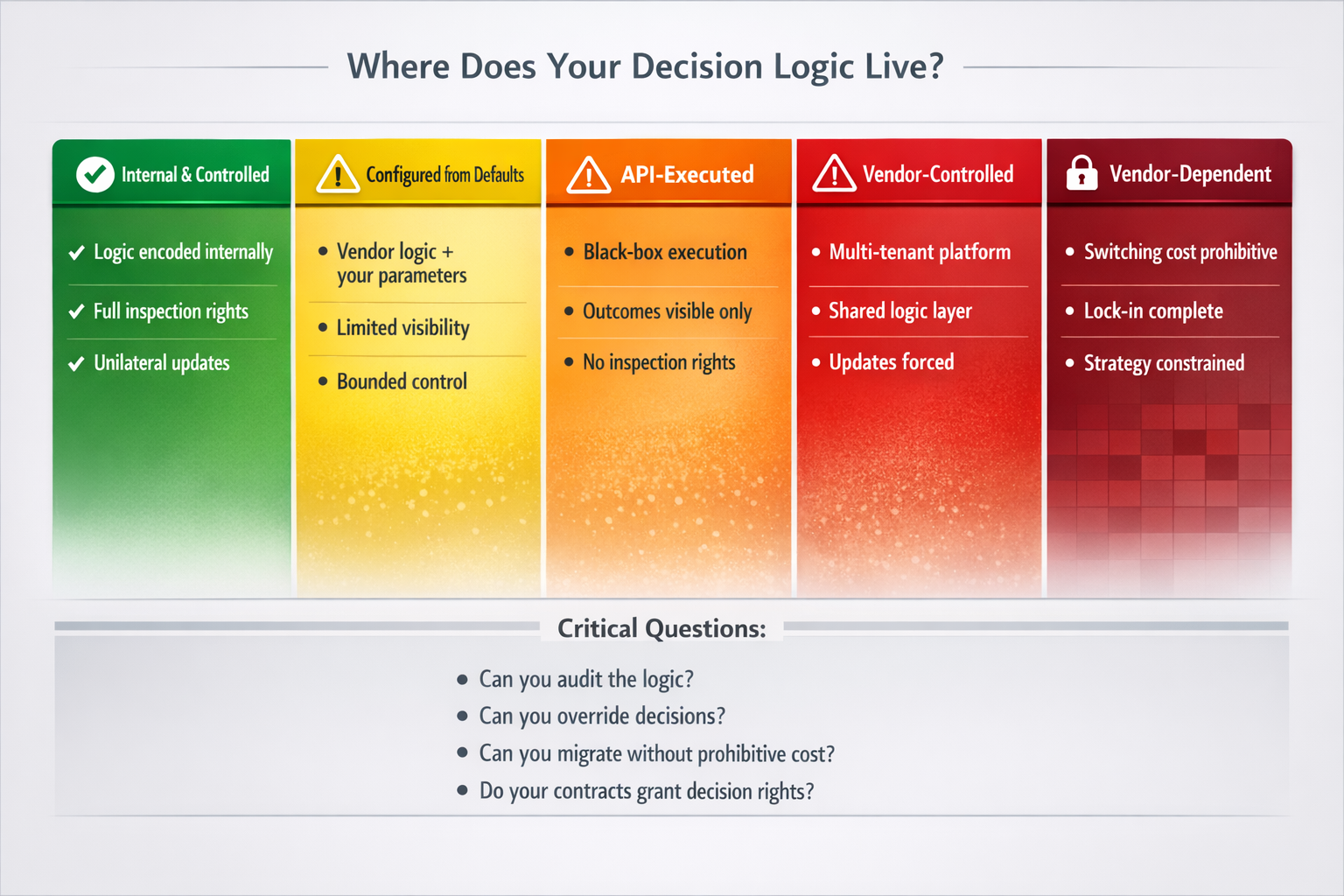

Second, trace logic ownership. For each decision point, identify whether the logic is:

- Encoded internally and fully controlled

- Configured from vendor defaults

- Executed by vendor API with limited visibility

- Determined by a vendor model with no inspection rights

Third, assess override capability. Can the enterprise change the logic unilaterally, or does it require vendor cooperation? Can it inspect how decisions are made, or only observe outcomes? What is the cost—technical, financial, organizational—of switching to a different logic source?

Fourth, evaluate contractual rights. Does the enterprise have the right to audit vendor logic? To demand changes? To migrate without prohibitive switching costs? Are there provisions for what happens if the vendor's updates conflict with the enterprise's strategy?

Fifth, identify concentration risk. If multiple critical decisions depend on a single vendor, that vendor has disproportionate influence over enterprise sovereignty. Concentration is not inherently bad, but it must be intentional.

What Leadership Must Govern

Once visibility exists, governance must shift. The question is no longer "does this tool work?" but "who controls the logic, and what are we trading for that?"

Some trade-offs are worth making. Sovereignty is not an absolute. Enterprises do not need to build every capability internally. But they do need to decide consciously which logic to own and which to delegate, based on strategic importance rather than procurement convenience.

High-sovereignty decisions—those that define competitive differentiation, embody ethical commitments, or carry existential risk—should not be governed by vendor logic unless the enterprise has contractual and technical rights to inspect, override, and migrate.

Low-sovereignty decisions—those that are commoditized, low-risk, or non-differentiating—can be safely delegated to vendor platforms, provided switching costs remain manageable.

The error most enterprises make is failing to distinguish between the two. They treat all software as equivalent and optimize for cost or speed, not for control. By the time they realize a particular decision point is strategic, they are already locked into a vendor's logic.

The Real Cost of Convenience

Vendor platforms offer speed, expertise, and economies of scale. These are real benefits. But they come with a cost that is rarely itemized: the gradual transfer of sovereignty from the enterprise to its vendors.

This is not a conspiracy. Vendors are not trying to steal control. They are optimizing for their business model, which requires standardization, reusability, and multi-tenancy. The misalignment is structural, not intentional.

But misalignment does not make it less real.

The enterprises that retain sovereignty in the age of AI will not be those that avoid vendors. They will be those that architect their dependencies deliberately, negotiate for decision rights explicitly, and measure control as rigorously as they measure cost.

Sovereignty is not lost in a single decision. It is lost in a thousand integrations, none of which seemed consequential at the time.

The question is not whether to use vendor tools. It is whether the enterprise knows which logic it must own, which it can delegate, and how to ensure it retains the right to change course when reality demands it.

In the age of AI, control does not reside in who owns the data.

It resides in who owns the logic that decides what to do with it.