This month, Waymo unveiled a world model that can simulate tornadoes tearing through intersections, elephants blocking highways, and snowstorms in tropical climates—scenarios its autonomous fleet has never encountered across 200 million miles of real-world driving. The achievement is remarkable: temporally consistent camera imagery and lidar point clouds, language-controlled scene manipulation, and multi-sensor realism that makes traditional 3D reconstruction obsolete. Built on Google DeepMind's Genie 3, trained on 50 million autonomous miles, and controllable across three axes—actions, layout, and language—it is the most sophisticated simulation of physical reality any AI system has produced.

Buried in the announcement is an admission that should reframe the entire conversation: an "efficient variant" is required for large-scale simulations because the full model cannot sustain long-horizon rollouts without computational collapse.

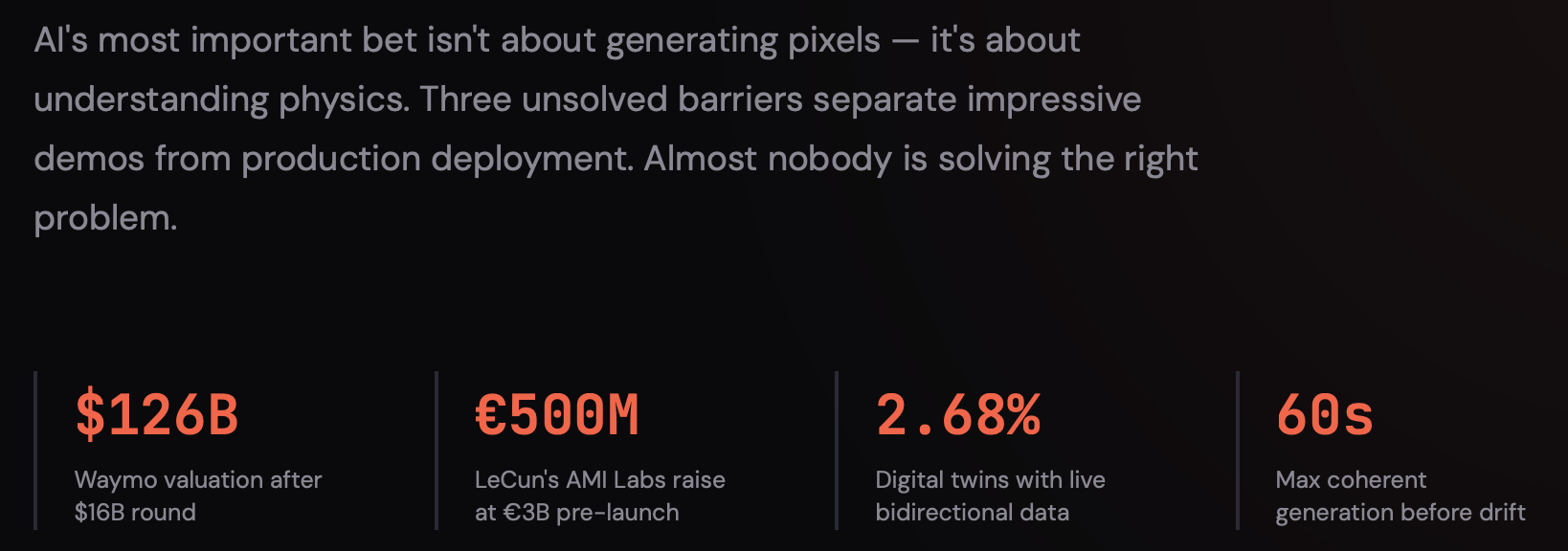

This pattern defines the state of world models in 2026: impressive visual fidelity coupled with fundamental limitations in temporal stability. Photorealistic sixty-second demos cannot extend to sixty minutes. A $126 billion valuation for a company whose simulation engine breaks when you need it most—at the edge of what it has seen before, sustained over the timescales where real decisions happen.

The autonomous driving simulation market is projected to reach $3 billion by 2030. Digital twin deployments are expected to grow from $23 billion to $200 billion over the next decade. Physical AI companies raised $7.5 billion in 2024. Yet a 2024 study found that only 2.68% of published digital twin systems operate with live bidirectional data, and only 14% of energy companies report that digital twins meet expectations. The gap between promise and production is not incremental; it is architectural.

The world model market does not have a quality problem; it has a category problem. Companies that understand the difference will define the next decade of AI infrastructure.

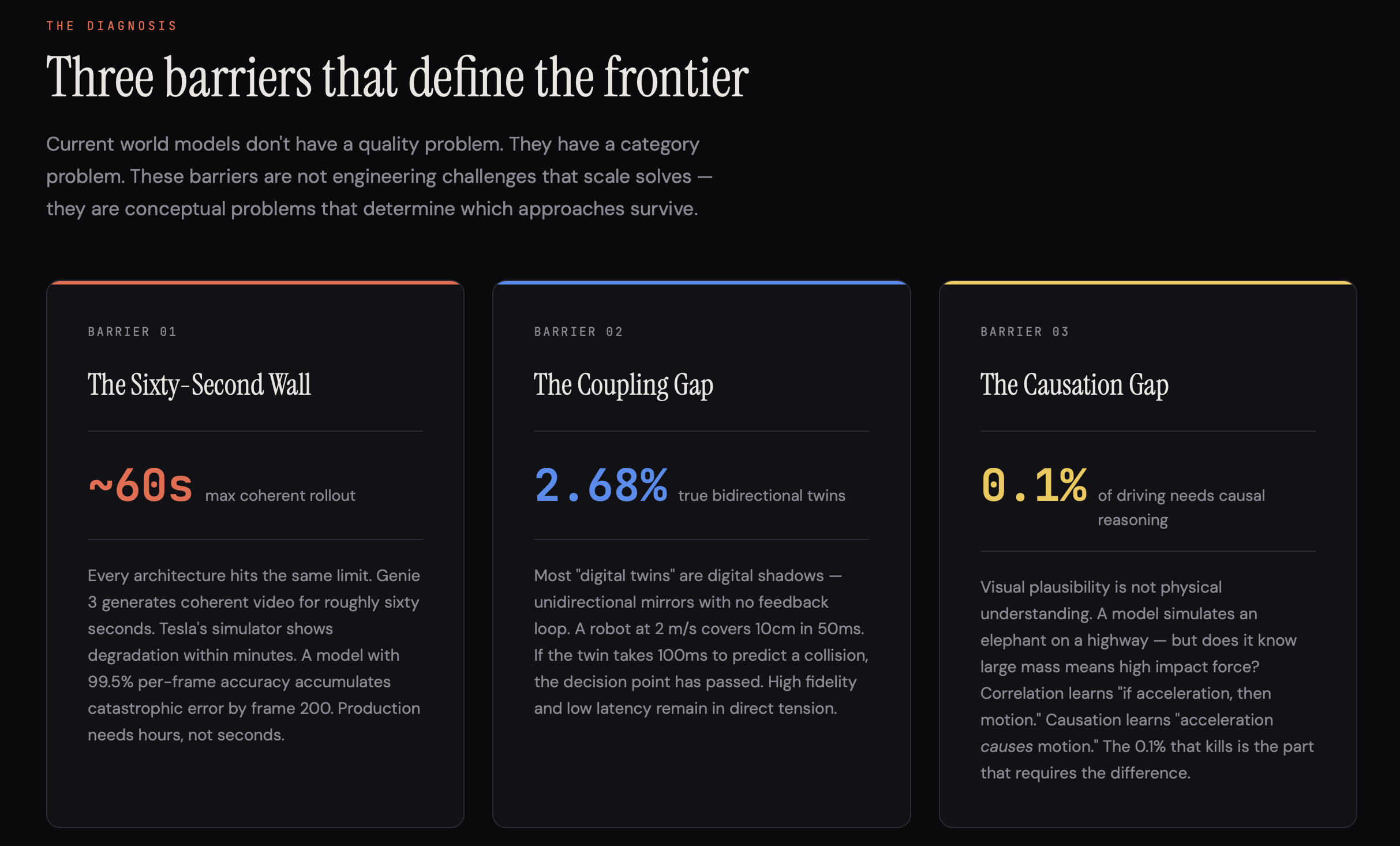

The Sixty-Second Wall

Every major world model architecture hits the same barrier. Genie 3 generates coherent video for about sixty seconds. Wayve's GAIA-3, with 15 billion parameters trained across nine countries, requires scene-specific fine-tuning for longer rollouts. Tesla's neural world simulator, trained on fleet data from over six million vehicles and reportedly synthesizing 500 years of driving experience per day, can produce minute-long sequences with noticeable quality degradation. The failure modes are diagnostic: objects deform during motion, vehicles teleport between frames, gravity stops applying, and pedestrians morph into lampposts.

These are not edge cases. They are the signature of a fundamental architectural limitation: compounding prediction error. Each generated frame serves as input to the next. Small errors in frame two cascade into hallucinations by frame one hundred. The mathematics are unforgiving. An autoregressive model with 99.5% per-frame accuracy accumulates enough error after 200 frames to produce outputs that barely resemble physical reality.

The emerging solution is hierarchical world modeling with memory: decomposing tasks into temporally extended "skills," predicting outcomes at the skill level rather than frame level, and maintaining explicit memory of earlier states. This is how humans plan. We do not predict the position of every molecule in a room when we decide to walk across it. We predict "I will reach the door" and fill in details only as needed. The SPlaTES framework showed that skill-level compensation enables stable long-horizon planning over entire episodes, not just brief windows. The Epona model achieved minute-long driving videos without noticeable drift via a chain-of-forward training approach.

But even these advances exist at the cutting edge of research, not in production. And the gap matters commercially. An autonomous driving validation pipeline needs hours, not minutes. A manufacturing digital twin needs to predict equipment behavior over the course of weeks. A robot learning to fold laundry needs to maintain spatial understanding across hundreds of manipulation steps. The difference between a sixty-second demo and an hour of operational stability is the difference between a research publication and a product.

The 2.68% Problem

If temporal drift is the most visible limitation, bidirectional coupling is the most commercially consequential. A 2024 study found that only 2.68% of published digital twin systems operate with live bidirectional data — meaning sensors feed the virtual model, predictions trigger physical interventions, outcomes generate new sensor data, and the loop closes continuously.

That number should alarm anyone who has seen the market projections. The digital twin market is valued at $23 billion and forecast to reach over $200 billion by 2033. But strip away the marketing, and the vast majority of what gets called "digital twin" is actually a digital shadow: unidirectional data flows that mirror reality without interactive feedback. BMW simulates factory layouts across 30 plants and one million square meters. Impressive — but these are offline optimization tools, run between deployment cycles. Foxconn claims real-time bidirectional data flow. In practice, humans still close every high-consequence loop.

The barriers are not just computational; they are architectural. Physical systems generate sensor streams at very different sampling rates: axis positions at 1kHz, temperature at 1Hz, and operator inputs at irregular intervals. World models like Genie 3 require seconds per generated frame. A factory robot moving at two meters per second covers 10cm in 50 milliseconds. If the digital twin takes 100ms to compute a collision prediction, the robot has already moved past the decision point. High fidelity and low latency are in direct tension, and no current architecture resolves this tradeoff at control-grade reliability.

There is also the problem of continuous learning. When a physical system diverges from prediction, as it inevitably will, should the model adjust its parameters? How quickly? Traditional engineering uses Kalman filters for state estimation. Modern learned models have hundreds of millions of parameters. Continuous updates risk catastrophic interference: new data can overwrite the generalizations that made the model useful.

The National Academies' December 2025 report on digital twins was direct about the gap: data assimilation from multiple sources at different scales and uncertainty levels remains an unsolved engineering challenge. The 2.68% figure is not a temporary deployment lag. It reflects the architectural difficulty of making learned world models operate reliably in closed control loops.

The Causation Gap

The third barrier is the most subtle and perhaps most consequential. Current world models can generate a photorealistic video of a candle melting, but cannot explain why the candle melts. The distinction sounds academic. It is not.

When Waymo's world model simulates an elephant on a highway, it produces visually plausible pixel values. But does it understand that a large mass implies a high impact force, which implies evasive action required? Or does it paste "elephant" into "road" based on learned visual correlations? When it simulates a tornado at an intersection, does it model wind forces and debris trajectories, or does it apply a learned texture of "tornado-ness" to an existing scene?

The question cuts to the heart of what world models are for. A model trained on summer driving data fails in snow, not because it has not seen snow, but because it does not understand that a lower coefficient of friction causally affects braking distance. A model trained on falling objects can generate plausible falling animations without knowing that mass and air resistance determine trajectories. Statistical correlation produces outputs that look right. Causal understanding produces outputs that are right, even in scenarios the model has never encountered.

The December 2025 CWMI framework addressed this problem directly, introducing a Causal Physics Module trained not on next-frame prediction but on causal intervention loss—predicting outcomes of hypothetical physical interventions rather than correlating observations. The distinction is precise: correlation learns "if I see acceleration, I see motion." Causation learns "acceleration causes motion, and if I change the force, the acceleration changes proportionally." The ACM Computing Surveys paper "Understanding World or Predicting Future?" framed the dichotomy as a fundamental divide in the field's identity.

This matters for deployment in three specific ways. First, out-of-distribution generalization: without a causal structure, models cannot extrapolate beyond their training distribution. Second, counterfactual reasoning: safety validation requires answering "if I had not braked here, would a collision have occurred?"—a question statistical models cannot address. Third, long-tail edge cases: 99.9% of autonomous driving is pattern matching, but the remaining 0.1%—the situations that cause fatalities—demand physical reasoning.

LeCun has been the most forceful articulator of this position. His critique is fundamental: if a model can generate a video of a ball rolling down a hill but cannot answer "how would the trajectory change if I kicked it harder?", it has memorized probability distributions, not physics. This conviction drove him to leave Meta in late 2025 and found AMI Labs, seeking €500 million at a €3 billion pre-launch valuation to build world models based on JEPA — an architecture that predicts in abstract representation space rather than pixel space, reasoning about outcomes without wasting capacity on irrelevant visual detail.

Three Strategies, One Industry

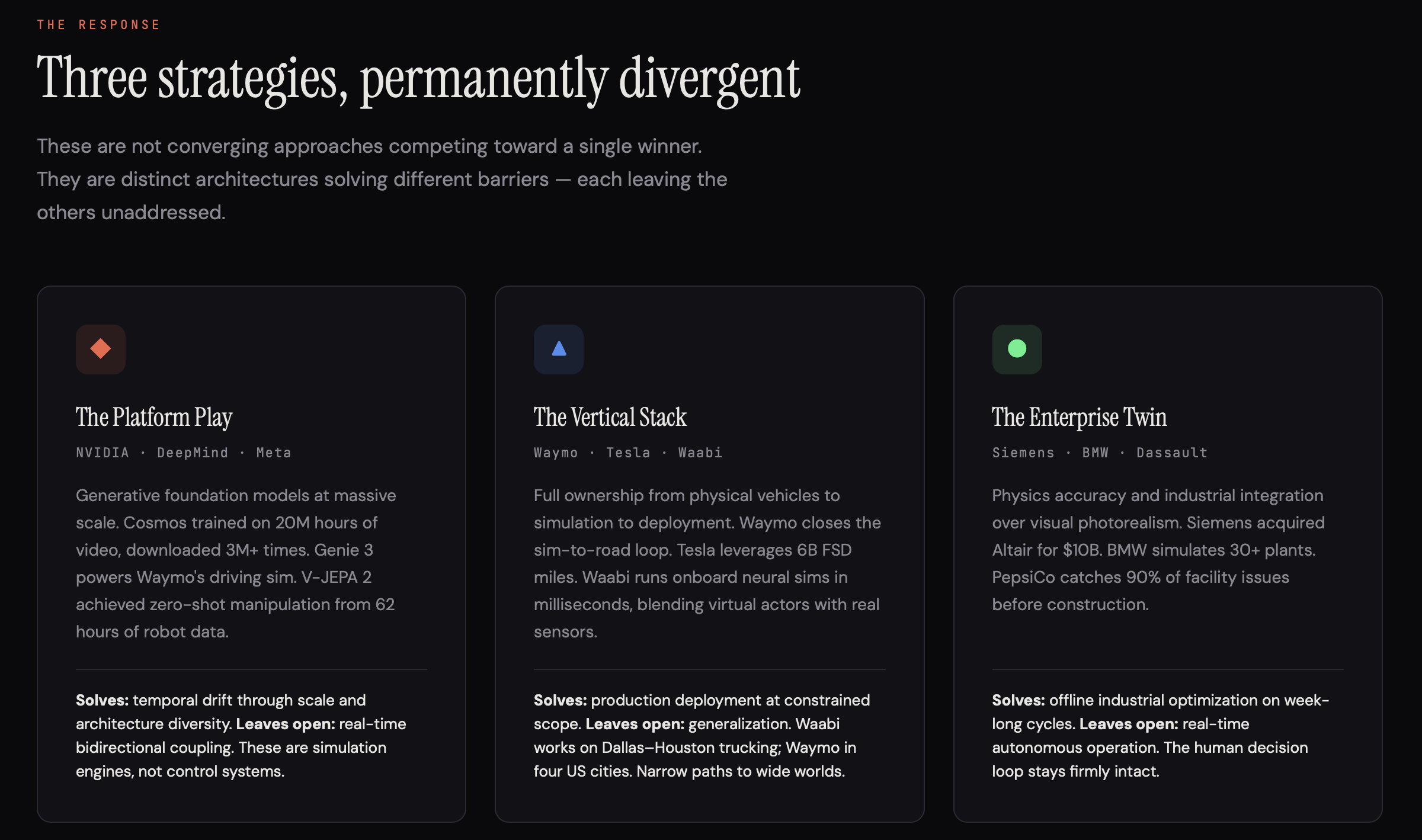

The competitive response to these barriers reveals three distinct strategies, each addressing different problems while leaving others unresolved.

The platform play—NVIDIA, DeepMind, Meta—bets on generative foundation models at scale. NVIDIA's Cosmos, trained on 20 million hours of video, has been downloaded over 3 million times. DeepMind's Genie 3 provides the backbone for Waymo's driving simulation. Meta's V-JEPA 2, pre-trained on over a million hours of internet video, then adapted with just 62 hours of robot data, achieved zero-shot manipulation in novel environments — arguably the strongest evidence yet that abstract prediction outperforms pixel generation for physical reasoning. These companies address temporal drift through architectural diversity and scale, but explicitly sacrifice real-time bidirectional coupling. Cosmos and Genie 3 are simulation engines, not control systems.

The vertical integration play—Waymo, Tesla, Waabi—controls the full stack from physical vehicles to simulation to deployment. Waymo closes the loop between the world model and driving: simulation generates edge cases, the Waymo Driver trains on them, real-world driving validates them, and logs feed back into the simulation. But this loop is offline; the world model does not run in real time during driving. Tesla maximizes data volume, with 6 billion FSD miles generating a training signal at a scale no competitor matches. Waabi has come closest to true real-time coupling: its onboard neural simulator runs in milliseconds, blending simulated actors with real sensor data during live driving, but only within the narrow scope of highway trucking between Dallas and Houston. The pattern is clear: vertical integration enables production deployment, but only to a limited extent.

The enterprise digital twin play—Siemens, BMW, Dassault—prioritizes physics accuracy and integration with existing industrial systems. Siemens's $10 billion acquisition of Altair Engineering and its new partnership with NVIDIA for "Industry World Models" signal serious intent. PepsiCo uses Siemens digital twins to identify up to 90% of potential facility issues before construction. But these remain planning tools operating on weekly cycles: design, simulate, adjust, construct—not real-time autonomous systems. The human decision loop stays firmly intact.

The strategic insight is that these are not converging strategies competing toward a single winner. They are permanently divergent architectures serving different barrier priorities. Safety-critical applications will prioritize causal understanding and uncertainty quantification. High-volume training will prioritize speed and scale. Manufacturing will continue physics-first hybrid approaches. The "universal world simulator" remains aspirational.

This divergence has implications for market structure. Autonomous driving simulation will consolidate around vertically integrated players and specialized providers like Applied Intuition, not general-purpose foundation models. Robotics training will commoditize around open platforms such as NVIDIA Isaac and MuJoCo, with application-specific fine-tuning on top. Manufacturing digital twins will remain fragmented across enterprise vendors with domain expertise: Siemens for industrial automation, Dassault for aerospace, and Ansys for materials science. The winning strategy in one segment may be irrelevant in another.

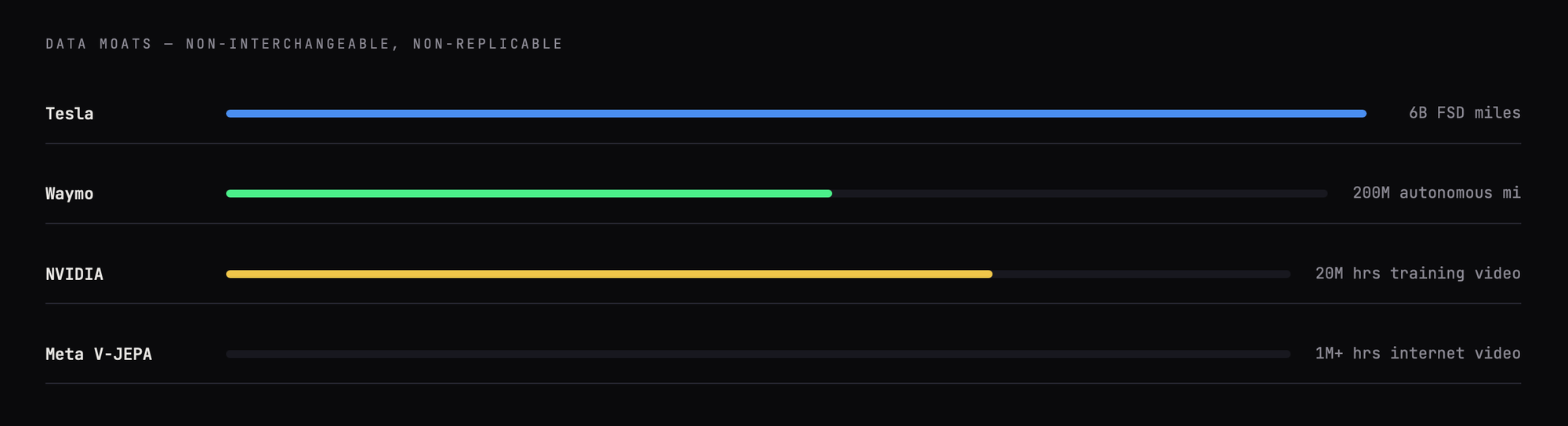

Data moats reinforce the divergence. Waymo's 200 million autonomous miles, Tesla's 6 billion FSD miles, and NVIDIA's 20 million hours of training video are not interchangeable. Waymo's data improves Waymo's driving simulation; it does nothing for factory optimization. Tesla's fleet data improves FSD; it is useless for robotic manipulation. The world model era will not produce a single dominant platform as ChatGPT did in text. It will produce domain champions, each moated by proprietary physical-world data that took years and billions of dollars to accumulate.

What Comes Next

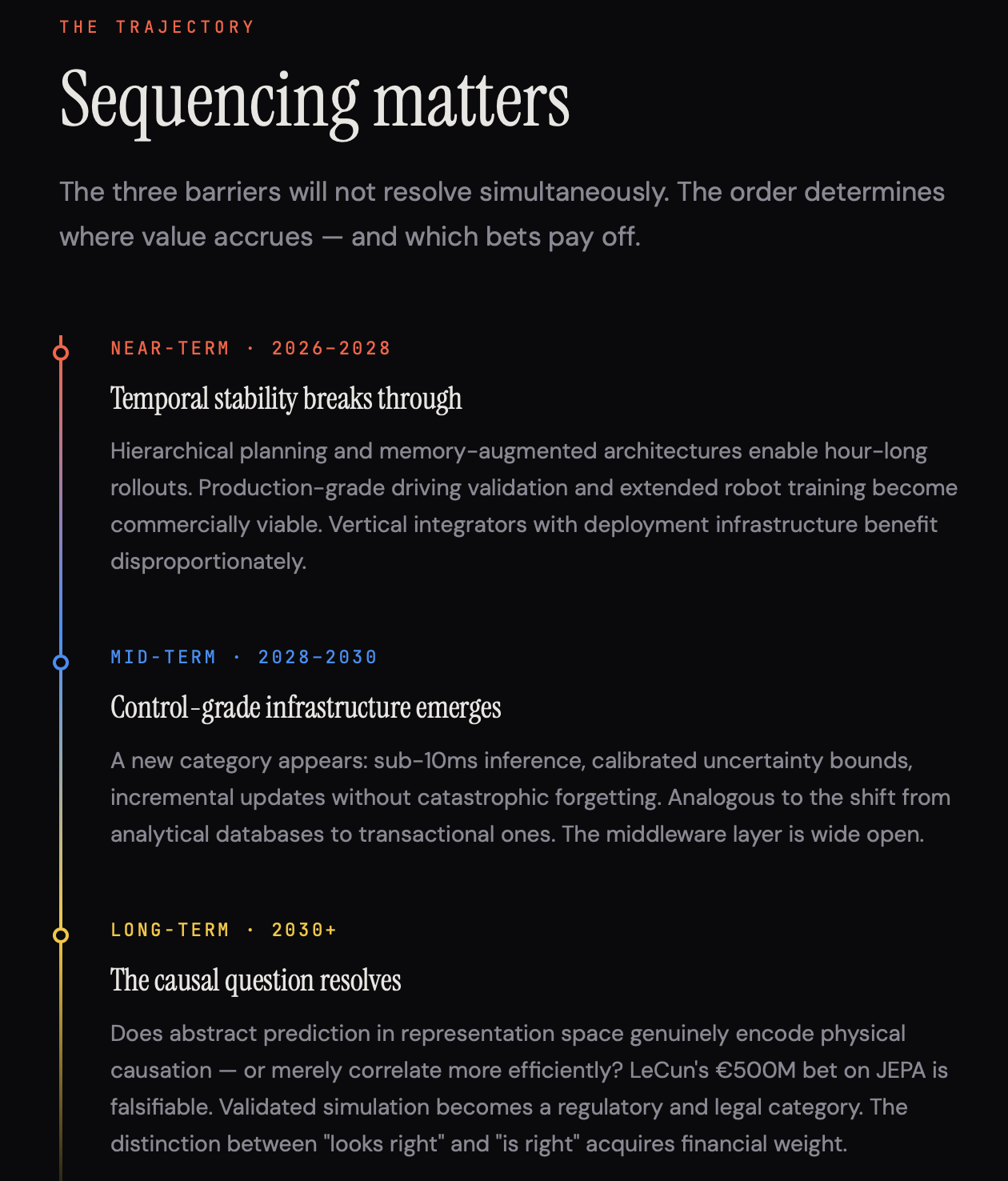

The resolution of the three barriers in world models will not occur simultaneously, and the sequence matters for where value accrues.

Temporal stability will improve first, driven by hierarchical planning and memory-augmented architectures. Expect commercially viable hour-long rollouts within two to three years, unlocking production-grade validation of autonomous driving and extended robot training episodes. This benefits vertical integrators disproportionately — companies with both the simulation technology and the deployment infrastructure to close the loop.

Bidirectional coupling will drive a new infrastructure category: control-grade world models, analogous to the evolution from analytical databases to transactional ones. This requires sub-10ms inference latency, calibrated uncertainty bounds, incremental updates without catastrophic forgetting, and hardware co-designed for deterministic timing. NVIDIA's position in compute hardware makes it the natural platform provider, but the middleware layer translating between high-fidelity offline simulation and low-latency online control is wide open.

Causal understanding is the longest horizon and the highest stakes. LeCun's €500 million bet on JEPA-based world models is explicitly a bet that this is the binding constraint. If he is right—if abstract prediction in representation space genuinely encodes physical causation while pixel prediction merely memorizes correlation—then the entire generative world model ecosystem is building on the wrong foundation. If he is wrong, the V-JEPA architecture becomes an efficiency improvement rather than a paradigm shift. The early evidence is provocative: V-JEPA 2 achieved zero-shot robotic manipulation with just 62 hours of real-world data after pre-training on internet video, a sample-efficiency advantage that suggests that abstract prediction captures something that pixel prediction misses.

A fourth development will emerge from the first three: validated simulation as a regulatory category. TÜV SÜD has already issued the first certification for an autonomous driving simulation platform. UNECE's R157 regulation accepts simulation evidence for highway driving system approval. As world models mature, the ability to provide formal guarantees of physical correctness—not just visual plausibility—will determine which simulations regulators accept for safety certification, which insurance companies price based on digital twin predictions, and which scientific applications trust model outputs for consequential decisions. The distinction between "looks right" and "is right" will acquire legal and financial weight.

The 2020s established that scale works. Foundation models trained on internet-scale data achieve remarkable capabilities. The 2025–2026 inflection point reveals the limits: temporal stability beyond sixty seconds, bidirectional control at millisecond latency, and causal reasoning beyond correlation. These are not problems that more parameters solve. They require new architectures, new infrastructure, and a more honest reckoning with what it means for a machine to understand the world it inhabits.

The gap between machines that can imagine scenes and machines that can live in them is not a matter of incremental progress. It is the difference between a technical curiosity and the foundation of a trillion-dollar infrastructure layer. The companies that understand which problems they are solving and which they are not will be the ones still standing when demos give way to deployment.