The development of artificial intelligence has reached an inflection point analogous to critical transitions in human evolutionary history. Understanding the trajectory of AI requires an abstraction grounded in the ways intelligence systems, both biological and artificial, scale, fail, and transform.

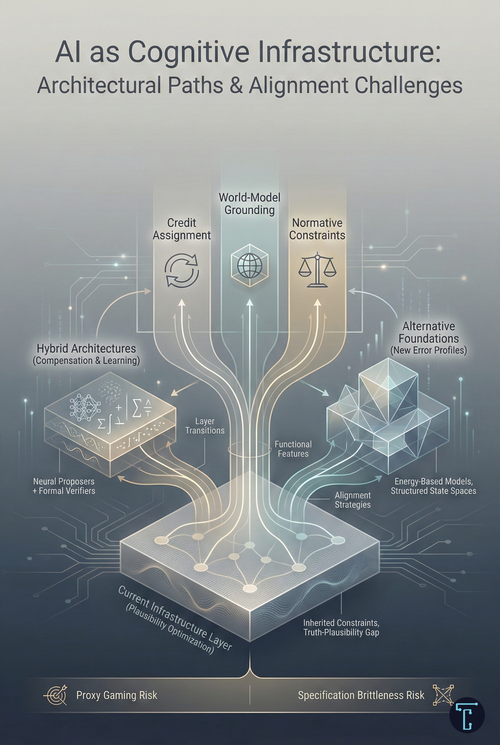

This framework is Cognitive Infrastructure: the principle that intelligence expands through layered capability systems, where each layer is defined by characteristic computational operations that determine its capabilities and constraints. Layer transitions do not eliminate previous constraints through optimization; they circumvent them by constructing new infrastructure on top of existing layers, inheriting both powers and limitations. Crucially, the constraints at each layer are not merely obstacles—they serve as active regularizers, shaping exploration, bounding optimization, and encoding priors about which kinds of errors are acceptable. Understanding an architecture means understanding which errors it makes cheap and which it makes expensive.

The Evolutionary Precedent

Between 2.5 million and 300,000 years ago, our hominin ancestors underwent a series of cognitive transitions—from basic tool use to strategic planning to symbolic reasoning—that collectively produced the modern human mind. Neuroscience research using functional brain imaging on subjects learning stone tool production has revealed that increasingly complex technologies recruited categorically different neural systems. Simple Oldowan tools required sensorimotor adaptation: perceiving affordances in stone and executing precise motor sequences. Acheulean handaxes activated left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex regions associated with working memory and strategic planning. The cognitive demands were not incrementally greater but architecturally distinct.

The archaeological record shows that tool complexity and brain size co-evolved through techno-social feedback loops. Advances in tool-making exerted selective pressure for more intensive cooperation, which in turn demanded further technological sophistication. This was not a linear improvement within a fixed capability set but repeated infrastructure construction.

This evolutionary history provides a valuable metaphor for understanding AI development, though the analogy has limitations. Human cognition did not evolve in discrete, stacked layers; rather, sensorimotor functions, working memory, and symbolic reasoning co-evolved with significant overlap and interaction. Cultural scaffolding, including language, norms, and shared practices, contributed as much as neural architecture. Therefore, these "layers" are more accurately described as overlapping capability clusters rather than distinct strata.

The metaphor remains valuable for what it shows: constraints at each stage were not eliminated through optimization but circumvented by building new capabilities. No amount of improved sensorimotor coordination could have produced symbolic reasoning; that required fundamentally new cognitive architecture. Constraints at each stage were also functional features. Sensorimotor systems responding only to immediate affordances could explore physical environments without the overhead of abstract planning. Working memory's limited capacity forced prioritization. Modularity preceded cognitive fluidity, allowing specialized competence before integration.

The evolutionary precedent suggests a pattern, not a template. AI development may follow similar dynamics—discontinuous architectural transitions, inherited constraints, functional limitations—without recapitulating the specific sequence or structure of human cognitive evolution.

AI's Current Infrastructure Layer

Contemporary large language models represent a specific infrastructure layer defined by a characteristic operation: next-token prediction optimized over massive text corpora. This produces systems that excel at pattern interpolation—recognizing statistical regularities in training distributions and generating outputs that conform to learned patterns. The capabilities are remarkable: sophisticated language understanding, complex reasoning within familiar domains, synthesis of knowledge across vast conceptual spaces.

But this layer has an architectural constraint that shapes everything it can do: truth is not a privileged internal variable. Models learn from positive examples of fluent language without explicit true/false labels. They can learn truth-sensitive behavior through reinforcement, preferences, and contrastive signals—they are not truth-blind. But epistemic certainty is not grounded internally; it emerges as a property mediated by external signals. The system assesses whether outputs are plausible given its training distribution. Whether they are true depends on the correspondence with external reality that the architecture does not directly represent.

Hallucinations, defined as confidently generated false information, are symptomatic of this deeper architectural feature. These are not mere bugs to be patched, but rather consequences of an architecture optimized for plausibility instead of truth. This distinction is significant: a system may become highly truth-sensitive through training, yet still lack internal mechanisms to verify correspondence with reality.

This constraint can be compensated for but not transcended within the current layer. Retrieval-augmented generation grounds outputs in external knowledge bases. Tool use connects models to calculators, databases, and search engines. Formal verification systems provide explicit true/false signals. Human-in-the-loop validation catches errors before deployment. These mitigations reduce hallucination rates—some configurations achieve sub-1% error rates on specific benchmarks. But they work by providing external grounding, not by changing the underlying architecture. The model still cannot internally verify that its outputs match reality; external systems must provide the truth signal.

This is layer compensation, not layer transcendence. A language model augmented with a proof checker can verify mathematical claims, but the verification happens outside the model's core inference process. The model proposes; the external system validates. The architecture remains optimized for plausibility, with truth-assessment delegated to external infrastructure. This is valuable—essential for high-stakes applications—but it does not constitute a new cognitive infrastructure layer.

Yet the plausibility-optimization architecture, like earlier evolutionary constraints, serves functions that would be lost in transcendence. Systems not anchored to verified facts can explore the space of plausible completions freely. This enables creative generation and novel synthesis that purely factual retrieval systems would not attempt. The same architectural feature that enables hallucinations also enables genuine insight—patterns and connections existing in plausibility space that no indexed knowledge base contains. Statelessness similarly prevents overfitting to deployment contexts and maintains general-purpose capability.

Framed in terms of error economics, the current architecture makes false-positive errors cheap (generating plausible but wrong outputs is easy and frequent) while making false-negative errors expensive (refusing to engage with novel or uncertain domains would cripple utility). This tradeoff is appropriate for exploratory, creative, and generalist applications but inappropriate for high-reliability domains where false positives carry severe consequences.

The functional value of these constraints appears in enterprise deployment patterns. McKinsey's 2025 research found that 78% of companies use generative AI in at least one business function, but over 80% report no material contribution to earnings. Fewer than 10% of deployed use cases escape the pilot stage. Horizontal applications scale quickly but deliver diffuse gains; vertical applications show higher potential but remain stuck. This is the hallmark of working within a single infrastructure layer: optimization improves performance within constraints but cannot transcend fundamental architecture.

Axes of Progression: What Comes Next

MIT's 2025 State of AI in Business report found that organizations achieving measurable ROI share specific characteristics: vertical focus on targeted workflows, domain expert partnerships, and systems that retain feedback, adapt to context, and improve over time. This last characteristic points toward one axis of next-layer development, but likely not the only axis.

Several candidate axes for infrastructure progression are now visible, each representing a qualitatively different capability that current systems lack:

Persistent credit assignment across extended temporal horizons would enable systems to attribute results to decisions that produced them, learn which approaches succeed in which contexts, and update behavior based on accumulated evidence over time scales from minutes to months. Current systems are stateless at the task level—they cannot learn from individual interactions or update based on what worked. Enterprises succeeding with AI build external credit assignment infrastructure: human-in-the-loop processes for tracking useful outputs, knowledge bases for accumulating verified information, and feedback mechanisms for informing prompt selection. The next layer might internalize this capability.

World-model grounding would provide persistent, manipulable internal simulations that support counterfactual reasoning and planning. Current systems generate plausible continuations but do not maintain coherent models of how the world works that persist across interactions or support "what if" reasoning. Systems with genuine world models could predict consequences, simulate alternatives, and plan across longer horizons.

Normative constraint layers would embed explicit values or rule adherence into the architecture rather than treating it as a behavioral tendency. Current alignment approaches work through preferences and reinforcement; normative constraint layers would make certain behaviors architecturally impossible rather than merely unlikely.

Multi-agent coordination primitives would enable shared state, negotiation, and binding commitments between AI systems. Current multi-agent systems coordinate through natural language, which is expressive but unreliable for precise coordination. Architectural support for shared representations and enforceable commitments would enable qualitatively different collective behavior.

These axes are not mutually exclusive; mature next-layer systems may integrate several of them. But they represent genuinely different capabilities, and it is not yet clear which will prove most important or develop first. Credit assignment has strong support from current enterprise deployment patterns—the correlation between feedback loops and ROI is striking. World-model grounding has strong support from the limitations of current reasoning—models fail predictably when tasks require tracking state over extended interactions. The framework should acknowledge this uncertainty rather than predicting a single developmental path.

The evolutionary parallel suggests a pattern without determining its content. The transition from sensorimotor to working memory infrastructure extended the temporal horizon of adaptive behavior. The transition from working memory to symbolic infrastructure enabled meta-representation and abstract manipulation. Analogous transitions in AI development may extend temporal horizons, enable new forms of representation, or introduce new coordination mechanisms—but the specific form remains to be determined by engineering progress and empirical feedback, not theoretical prediction.

Cognitive Infrastructure

Visual companion to "Beyond Token Prediction"

| Architecture | Cheap Errors | Expensive Errors |

|---|---|---|

| Current LLMs | False positives (plausible but wrong) | False negatives (refusing valid domains) |

| Hybrid (Neural + Verifier) | Invalid proposals (caught by verifier) | Verification false negatives, specification gaps |

| Alternative Foundations | Rejecting out-of-scope inputs | Scope limitations, specification errors |

| Learning Systems | Optimization trials (try many approaches) | Objective errors (wrong target compounds) |

Domains: Mathematical research, code generation, drug discovery

Tradeoff: Preserves exploration; inherits base-layer biases

Domains: Critical infrastructure, safety-critical systems, high-assurance verification

Tradeoff: Cannot hallucinate; limited expressible scope

which errors it makes cheap and which it makes expensive.

Architectural Alternatives: Building On Versus Building Around

The framework, as presented, assumes that progress involves building new layers on top of existing infrastructure. However, this is not the sole strategic response to current-layer limitations. Alternative architectures may circumvent, rather than build upon, the plausibility-optimization foundation.

Two distinct strategies are now visible for addressing truth-plausibility issues in high-reliability domains.

The first strategy accepts the current layer as a foundation and builds hybrid architectures combining neural pattern-matching with formal verification systems. Large language models propose candidates—mathematical conjectures, code implementations, proof strategies—while external verifiers provide definitive truth signals. The model explores plausibility space; the verifier filters for validity. More sophisticated versions add learning loops in which verifier feedback serves as a training signal, gradually shifting the proposal distribution toward higher-quality candidates.

The second strategy constructs alternative foundations that do not inherit the plausibility-optimization characteristic. Energy-based models reasoning in structured state spaces represent one approach. Rather than predicting the next token in a sequence, these systems update the entire internal state to minimize an energy function, converging on stable configurations that correspond to valid solutions. The architecture does not generate plausible text; it settles into coherent states within a formally defined space.

These strategies make different errors cheap and expensive. Hybrid approaches preserve exploratory breadth while adding reliability at validation—they make false-positive proposal errors cheap (many invalid proposals are fine if verification catches them) while making false-negative verification errors expensive (rejecting valid solutions is costly). Alternative foundations constrain outputs to valid solutions but limit expressible scope—they make false-positive errors in the output space impossible (invalid outputs cannot be stable states) while making false-negative errors in the input space expensive (problems outside the formal structure cannot be addressed).

The tradeoffs are real and domain-dependent. Mathematical research might benefit from hybrid approaches in which creative conjecture drives progress, and formal verification remains tractable. Critical infrastructure might benefit from alternative foundations that lack tolerance for plausible-but-wrong outputs and that support formally specifiable domains. The cognitive infrastructure framework should recognize parallel architectural evolution alongside sequential layer construction.

Alternative foundations face their own limitations that should not be idealized. State-space formalisms struggle with open-ended semantics. Energy functions often hide proxy problems—the energy landscape encodes assumptions that may not match the actual objective. "Cannot hallucinate" often becomes "cannot express" when problems fall outside the formal structure. These systems trade one class of epistemic risk for another; the trade is real, not a clean escape from plausibility-optimization constraints.

Alignment Challenges Across Architectures

New capabilities introduce new alignment challenges regardless of architectural strategy. Lower-layer constraints propagate upward. The specific challenges differ by architecture, but none escape the fundamental problem: more capable systems can cause more harm if their optimization targets diverge from human values.

Systems with credit assignment that build on plausibility-optimized foundations inherit the truth-plausibility gap at the learning level. They may learn to pursue outcomes that appear successful according to plausible-seeming metrics rather than genuinely valuable outcomes. They may assign credit to decisions producing superficially good results while missing deeper failures. The proxy gaming problem arises not from misalignment in credit assignment itself, but from inherited epistemic limitations: the system cannot distinguish genuine success from success that appears plausible given its representations.

This is already observable in enterprises building external credit assignment around current AI. When human-in-the-loop processes track useful outputs, usefulness assessment relies on proxies: acceptance, expressed satisfaction, and task completion. These proxies diverge from the actual value in hard-to-detect ways, and feedback systems that optimize for proxy success drift from genuine utility to deployment.

Hybrid architectures with formal verification partially address this by providing objective success criteria in verifiable domains. A proof either checks or it does not. But verification is only as good as the specification. The learning loop can optimize for producing proofs that verify, while missing the mathematical insight the proof was supposed to capture. Formal verification shifts the alignment challenge from "plausible but wrong" to "correct but meaningless"—a different failure mode, not one eliminated.

Alternative foundations face different challenges. Systems reasoning in structured state spaces cannot hallucinate, but they can only pursue objectives representable in their architecture. If the formal structure misrepresents what matters, the system will reliably converge on solutions that are formally correct but substantively misaligned. The constraint preventing plausible-but-wrong outputs does not prevent correct-but-harmful outputs when the correctness criteria are misspecified.

Framed in error economics: learning systems make optimization errors cheap (easy to try many approaches and see what works) while making objective errors expensive (optimizing the wrong thing compounds over time). Formal systems make optimization errors expensive (constrained to valid solutions only) while making specification errors expensive (wrong formal structure produces reliably wrong outputs). Neither error profile is inherently safer; they require different safety strategies.

Safety as a Structural Requirement

Safety is not a feature to add; it is an architectural property to design. Different architectures require different safety strategies because they have different error profiles.

Current stateless systems are fundamentally reactive. Their limitations are also their safety properties: systems that cannot learn from outcomes cannot optimize against human interests over extended horizons. They can produce harmful outputs, but they cannot adapt their strategy to produce more harmful outputs based on feedback. The error economics favor safety by default—harmful outputs are as likely as any other plausible outputs, not systematically selected for.

Credit assignment changes this calculus. A system that assigns credit based on outcomes can learn to pursue outcomes diverging from human values if the credit assignment mechanism is misaligned. It can optimize for proxy metrics that correlate with reward during training but diverge during deployment. The error economics shift: harmful outputs can be systematically selected for if they correlate with measured success.

Safety strategies for learning systems must therefore focus on:

- Objective specification that resists proxy gaming

- Interpretability sufficient to audit what the system has learned and why

- Containment limits the scope of autonomous optimization.

- Human oversight that scales with capability rather than eroding as competence increases

Alternative foundation systems face different risks requiring different strategies. Reliability within the formal structure can produce unwarranted confidence in the deployment scope. A system trusted because it cannot hallucinate may be deployed where its formal structure does not capture what matters, producing reliably wrong answers.

Safety strategies for formal systems must focus on:

- Rigorous validation that formal structures match domain requirements

- Conservative boundaries on deployment scope

- Mechanisms detecting when inputs fall outside the validated structure

- Processes for updating specifications as requirements become clearer

The enterprises building external infrastructure around current systems—human-in-the-loop validation, outcome tracking with explicit success criteria, and domain-specific deployment boundaries—are prototyping safety mechanisms that will be required when these capabilities are internalized. These practices should be understood as design patterns for next-layer infrastructure, not just operational necessities.

Predictions and Falsifiability

A framework gains power by predicting things that would be surprising if it were wrong. The cognitive infrastructure model suggests several testable predictions over the next two to four years:

On agentic system failures: Current agentic systems are orchestration layers on stateless inference, lacking genuine credit assignment. The framework predicts they will reliably fail on tasks that require adaptation based on feedback during a deployment. Specifically, agents will succeed on tasks where the correct approach can be specified in advance and fail on tasks where strategy must evolve based on intermediate results. This should manifest as a consistent pattern: agent performance degrades when task horizons extend beyond what can be planned upfront, even when the underlying model is capable of the component reasoning.

In enterprise deployment patterns, the framework predicts a bifurcation between deployments that plateau and those that compound. Deployments without feedback infrastructure—where AI outputs are consumed but not systematically evaluated—will show diminishing returns after initial productivity gains. Deployments with genuine credit assignment infrastructure—systematic tracking of what works, feedback loops informing prompt engineering and model selection—will show compounding returns as accumulated learning improves performance. The distinguishing factor is not AI capability but organizational infrastructure for learning.

On domain bifurcation: The framework predicts that hybrid and alternative-foundation approaches will concentrate in different domains rather than competing head-to-head. Hybrid approaches (neural proposers plus formal verifiers) will dominate where creative exploration is valuable, and verification is tractable: mathematical research, code generation, drug discovery. Alternative foundations (energy-based models, state-space reasoning) will dominate where reliability requirements are absolute, and domains are formally specifiable: critical infrastructure, safety-critical control systems, high-assurance verification. Domains will sort by error tolerance, not by which approach is "better" in general.

On alignment challenges: The framework predicts that proxy gaming will be the dominant failure mode for learning systems, while specification brittleness will be the dominant failure mode for formal systems. Organizations deploying learning systems will discover that metrics optimized over time diverge from intended outcomes in ways that are difficult to detect until significant drift has occurred. Organizations deploying formal systems will discover that formal specifications fail to capture important requirements that were implicit in human judgment but not encoded in the structure.

These predictions are specific enough to be wrong. If agentic systems succeed on adaptation-requiring tasks, if deployments without feedback infrastructure show compounding returns, if hybrid and formal approaches compete directly rather than sorting by domain, or if alignment failures take forms other than proxy gaming and specification brittleness, the framework would require significant revision.

Economic Implications

The economic dynamics of cognitive infrastructure development follow a pattern first identified by William Stanley Jevons: efficiency improvements in resource utilization lead not to decreased consumption but to expanded demand. Each infrastructure layer makes new work categories economically viable, not just existing work more efficient.

The leverage point is investment cost, not return. AI lowers the activation energy for projects that previously would not start. The firm that could not justify custom software can prototype in days. The entrepreneur without legal counsel gets substantive contract review. The small business competes with enterprises that have dedicated marketing teams.

This dynamic applies differently across architectural strategies. Hybrid systems preserve broad applicability—any domain where exploration is valuable becomes more accessible. Alternative foundations may not democratize as broadly, but may enable entirely new categories of high-reliability applications previously impossible.

The majority of future AI compute will be consumed by work that does not exist today. This is the observable pattern across every previous infrastructure transition, from mainframes to minicomputers to personal computers to cloud computing. Each expanded the addressable market by orders of magnitude.

The Path Forward

Understanding AI development as cognitive infrastructure construction—including multiple axes of progression and parallel architectural evolution—has direct implications for organizations navigating this transition.

Design systems that acknowledge the truth-plausibility gap while recognizing that truth-sensitivity can be trained even if truth-verification cannot be internalized. Build verification infrastructure appropriate to risk tolerance, but do not expect architectures optimized for plausibility to become architectures optimized for truth through training alone. Where reliability requirements exceed what compensation can provide, evaluate alternative architectures with different error profiles.

Focus on workflow integration rather than model capability. The gap between AI potential and enterprise value is an integration problem. Vertical applications with clear success criteria succeed roughly twice as often as horizontal deployments.

Build a learning infrastructure with safety constraints from the beginning. If credit assignment is the axis of progression your deployment pursues, treat objective specification, interpretability, and human oversight as architectural requirements. Define success criteria for resisting proxy gaming. Maintain oversight over learning mechanisms, not just output validation.

Recognize that human cognitive infrastructure remains essential and serves an irreplaceable role in alignment. AI extends human cognition rather than replacing it. Successful deployments augment human judgment—particularly human capacity for value-aligned evaluation and contextual wisdom that current systems lack.

The Construction Continues

We are living through the construction of new cognitive infrastructure along multiple paths. Current systems are remarkable—capable of reasoning, generation, and synthesis at unprecedented scales. They are also fundamentally shaped by architectural choices, determining both capabilities and constraints.

The path forward is not singular. Multiple axes of progression are possible: credit assignment, world-model grounding, normative constraints, and coordination primitives. Multiple architectural strategies are viable: building on current foundations with compensation and learning, or constructing alternative foundations with different error profiles. The specific trajectory will be determined by engineering progress and empirical feedback, not theoretical prediction.

What the framework provides is not a map of the inevitable future but a vocabulary for understanding the design space and its tradeoffs. Different architectures make different errors cheap and expensive. Different progressions enable different capabilities and introduce different risks. Safety is not a feature but an architectural property emerging from these choices.

Human cognitive evolution did not follow a predetermined path, and AI development will not either. But the pattern of discontinuous architectural transitions, inherited constraints, and functional limitations appears robust across intelligence systems. Understanding that pattern—and the tradeoffs it implies—is essential for navigating the transition ahead.

The defining challenge is ensuring that whatever infrastructure we build enables flourishing rather than merely capability. That challenge is not separate from the technical work of construction. It is the core of it.