From The Washington Post:

A new data protection law is changing the calculus for doing business in China, with foreign and domestic firms scrambling to comply, and some companies including LinkedIn and Yahoo choosing to leave.

China’s personal information protection law, implemented this month, is the latest factor adding to a challenging political environment for businesses operating in the country and altering the cost-benefit analysis. While the untapped business potential of 1.4 billion consumers was once an irresistible draw, this is increasingly changing.

While writing Tesla and China - The Synergies, I mentioned how China limits the growth of foreign or multinational companies using regulations. The country's new Personal Information Protection Law (PIPL), which took effect on November 1, 2021, is also a possible step and comes across as an isolationist framework to limit the operations of companies such as Apple and Tesla. PIPL builds on the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) and takes it further with provisions requiring companies utilizing Chinese personal data to lower the data collection and take prior permission. In addition, data localization also forms an essential part of the regulation. Considering most countries' rules concerning data security or protection, China's PIPL resembles them. However, it is different because it also allows the government to access the data. Additionally, the GDPR is defined based on data privacy, whereas PIPL seems to be based both on data privacy and data protection.

Before PIPL, China also brought the Cybersecurity Law and Data Security Law (DSL) into effect. The cybersecurity law mandates that network operators store select data within China. And the DSL provides a framework to classify private sector data based on the interests of the state, such as national security, and thus the regulations for storing and transferring data based on these classifications. These are efforts to tighten the controls over data flow.

From the companies' perspective, they may have to change their current operational practices and business models. Additionally, companies have had very little time to do so, considering that these regulations were passed and brought into effect in a short time, leaving the companies to grapple with decisions to either end their operations in the country or make the necessary changes. Essentially, in the future, these regulations would provide a primer to companies when deciding to enter a particular market such as China.

Timing and Dependencies

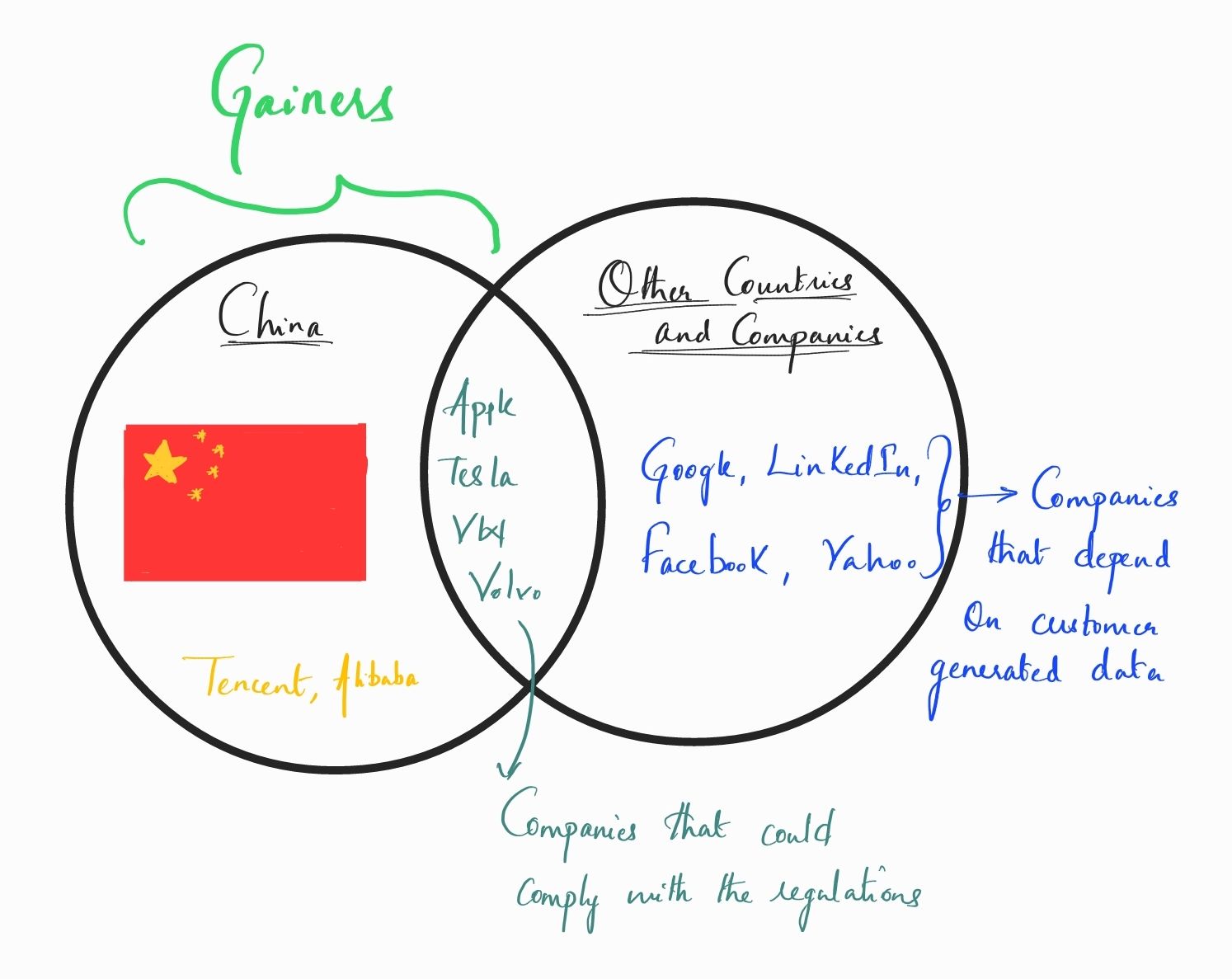

To understand the reasons behind these regulations, one needs to comprehend the timing of these regulations and the dependencies the country has created. China stands to benefit hugely from these two. Yes, one must factor in the changing dynamics of US-China trade and the listing of Chinese companies on the international stock markets. The government understands that companies such as Tencent, Alibaba, Apple, Tesla, etc., are vast repositories of data collected locally from customers. Multinational companies with operations and R&D outside China would move the data to their data centers and eventually derive actionable insights. With these actionable insights, the companies create a better real-time customer experience, better their products or services, and innovate further.

Data collection has become a norm with the influx of artificial intelligence, machine learning, the Internet of Things, sensors, edge computing, and mobile computing. New data collection technologies are emerging, which would only ensure that data collection would increase stupendously.

Yes, customers are the owners of their information; however, companies derive insights that are beneficial to their operations, and sometimes, these companies can use data licensing as their business model without the knowledge of the customers. However, the same data can also be helpful to the government to derive different sets of insights, given that it has other responsibilities, unlike these technology companies. This data is what the government of China expects to access and use. The end purpose of such access or usage is still debatable; perhaps it can use the data to ensure national security or track its citizens till the last inch of their movements. Essentially, data is a critical asset not only to the companies but also to the government.

The government, too, collects information about its citizens differently - perhaps through the government's institutions that provide social security numbers, health cards, driving licenses, and others. However, given the flux nature of our society, this information is relatively static to derive insights to foresee and stall a few situations that may be critical to the country. Data collected by Uber, Tencent, Alibaba, and others would help address this problem. Thus, the regulations come into effect, ensuring that the companies provide data access and customer data privacy.

The other way China could use this set of regulations is to slow down foreign companies, given that these regulations would necessitate changes in companies' practices and business models. Data localization rules also stifle innovation as the data that flows outside the country could help R&D innovate. This innovation, perhaps, could return to the country eventually, too. China does understand the repercussions of the retaliations on such rules - companies could end their operations in the country, other countries could also enforce such regulations on Chinese companies operating beyond China, innovation can slow down, etc. However, China has created critical dependencies for other countries and their companies as a vast market and a manufacturing and industrial hub. For a company, these dependencies could be supply chain dependencies. Moving the operations out of the country could be costlier and time-consuming, as China's benefits to these countries or companies are many, benefits which are hard to replicate by others.

Companies such as Facebook and Google that depend entirely on customers' generated data to provide their services would bear the major brunt of these regulations. For the same reason, these two companies are non-existent in the country. Yahoo and LinkedIn are choosing to cut their Chinese operations entirely. These regulations apply to companies such as Apple and Tesla, too. However, these companies could decide to comply with the rules as they do not wholly rely on customers' generated data. They have hardware products such as watches, mobile devices, and cars, and China provides a massive market for these products. The revenues derived by selling these products in China are not worth ignoring; instead, a company would take up the costs and time required to bring changes in its practices and business models by complying with the regulations introduced by China. For hardware-intensive companies such as Apple and Tesla, China creates a different nonignorable dependency.

Additionally, China can afford to lose companies such as Google, Facebook, and Twitter, as it has similar, if not better, service providers from within. Essentially, dependencies play a massive role in the changing dynamics between China and other countries (including their companies). How these dependencies change with time needs to be seen, as these countries plan to move a few of their dependencies elsewhere to countries such as Vietnam, India, or their own countries themselves. Globalization did help China immensely; however, localization seems to be taking its place.